When I first learned about John Addington Symonds and his studies of homosexuality in the Classical era, one figure came to my mind: Sappho. Sappho is often known as a female Greek poet considered homosexual. After all, the term lesbian came from the island Sappho lived on: Lesbos. Because of this, I thought Symonds would have studied the life of Sappho and probably left some comments about her in his work.

Indeed, in the Lost Library of Symonds, I found Sappho: Memoir, Text, Selected Renderings, and a Literal Translation by Henry Thornton Wharton. Symonds received this book as a gift copy from the author. In this book, Wharton cites Studies of the Greek Poets by Symonds. He even gives thanks to Symonds in his preface to the first edition of this book:

The translations by Mr. John Addington Symonds, dated 1883, were all made especially for this work in the early part of that year and have not been elsewhere published. My thanks are also due to Mr. Symonds for much valuable criticism.

Wharton Sappho xvi

Looking at Symonds’s contribution to this book, I realized how much he was interested in Sappho. Thus, I thought it would be a good starting point for Symonds’s thoughts on Sappho.

Wharton’s Sappho is a collection of Sappho’s poems and fragments with English translation, but he devotes one chapter to the life of Sappho. Though Sappho’s life is generally unknown due to a lack of records, Wharton provides details. Sappho was native to an island in the Aegean Sea called Lesbos. According to Herodotus, Sappho’s father was Scamandrymus, and her mother was Cleis. She also had a brother called Charaxus and Larichus. Suidas says Sappho was married to Cercolas and had a daughter named Cleis. Though the exact date is unknown, Sappho lived in the late 7th century BCE and early 6th century BCE. It is also unclear how long she lived, but Sappho describes herself as γεραιτέρα, somewhat old in fragment 75.

Wharton then cites Symonds’s Studies of Greek Poets to talk about the unique social condition of Lesbian poets. Symonds claims that Aeolian custom allowed women more social and domestic freedoms than the rest of Greece. This allowed women to be highly educated, interact freely with male society, and express their sentiments. This social condition of Lesbian women, Symonds suggests, allowed them to form clubs of poetry and music and develop their unique art. Sappho was at the center of this artistic society.

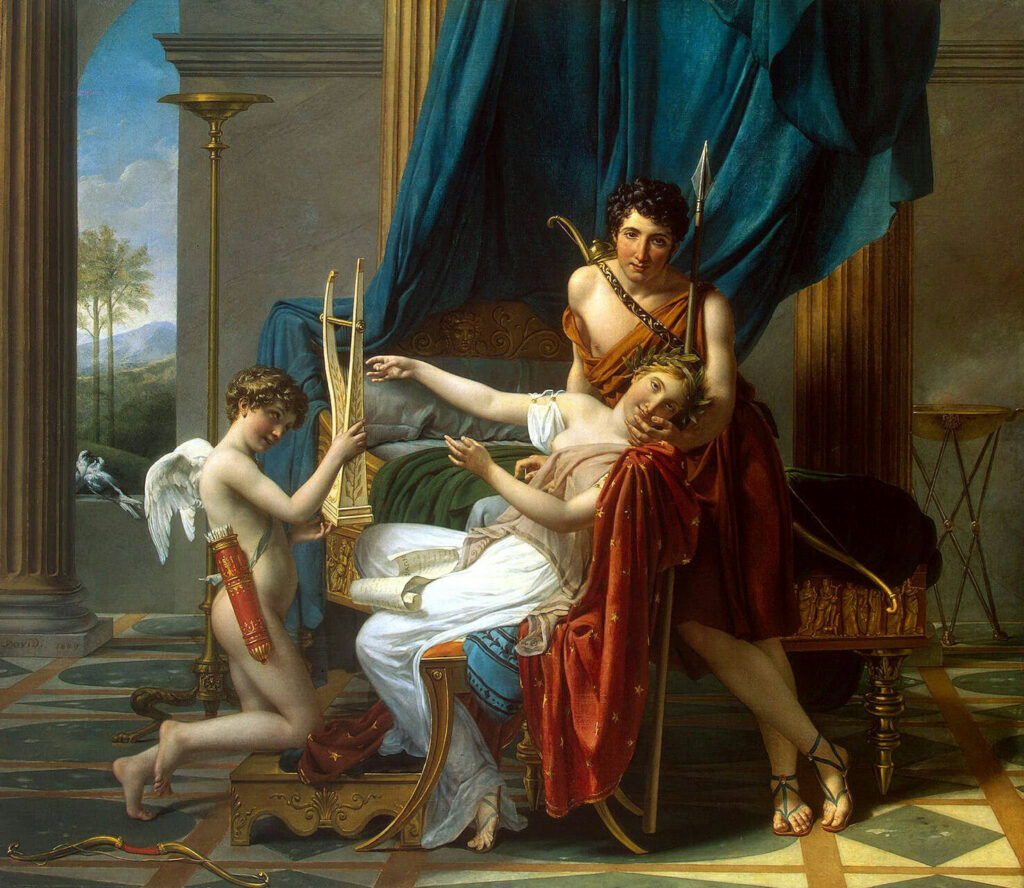

Meanwhile, Wharton examines Sappho’s pursuit of the beautiful young man named Phaon and her leap from Leucadian rock after she was rejected. Despite the uncertainty of whether it really happened, many ancient writers, including Ovid, mention this story. When I first looked at Sappho’s love for Phaon, I thought this would have been a potential counterexample of Greek male love proposed in Symonds’s A Problem in Greek Ethics, mainly Greek pederasty. Usually, the erastes, the lover, is limited to adult males, while eromenos, the loved, can be young males, females, or enslaved persons of either gender. However, in Sappho’s pursuit of Phaon, though she was unhappy and unsuccessful, she represents the adult woman acting as an erastes, which breaks the rule. I was interested in seeing Symonds’s response to this outlier.

However, Wharton states the story does not have a firm historical basis, since unlike the story of Sappho’s leap toward the sea, there are ancient records that she was buried in a grave (Wharton, 15). He also suggests that the entire story was derived from the myth of Aphrodite and Adonis, since Adonis is called Phaon in Greek (Wharton, 20). Also, the legend does not appear until Attic Comedy in 395 BCE, which is 2 centuries after Sappho’s death.

Symonds does not seem to consider Sappho’s pursuit of Phaon significant, but for a different reason. He briefly mentions the story of Sappho and Phaon in his Studies of Greek Poets:

About her life— her brother Charaxus, her daughter Cleis, her rejection of Alcæus and her suit to Phaon, her love for Atthis and Anactoria, her leap from the Leucadian cliff— we know so very little, and that little is so confused with mythology and turbid with the scandal of the comic poets, that it is not worthwhile to rake up once again the old materials for hypothetical conclusions. There is enough of heart-devouring passion in Sappho’s own verse without the legends of Phaon and the cliff of Leucas.

Symonds Studies of the Greek Poets 310

Symonds argues that the story of Sappho and Phaon and other stories of her pursuit are confused with mythology, as Wharton thinks. Then, he goes beyond by saying Sappho’s own verse is enough to show her passion. This shows that his interest was in Sappho’s own verse, on the assumption that it represents her actual voice.

Meanwhile, some fragments of Sappho’s poems describe female beauty and her love for another woman. Among many fragments, I found fragment 1 of Sappho, also known as “Hymn to Aphrodite”, worth discussing. This is the fragment that Symonds translated twice: once in his Studies of Greek Poets in 1877 and another time for Wharton’s Sappho in 1883.

Glittering-throned, undying Aphrodite,

Wile-weaving daughter of high Zeus, I pray thee.

Tame not my soul with heavy woe, dread mistress,

Nay, nor with anguish!

But hither come, if ever erst of old time

Thou didst incline, and listenedst to my crying.

And from thy father’s palace down descending,

Camest with golden

Chariot yoked: thee fair swift-flying sparrows

Over dark earth with multitudinous fluttering,

Pinion on pinion, thorough middle ether

Down from heaven hurried.

Quickly they came like light, and thou, blest lady,

Smiling with clear undying eyes didst ask me

What was the woe that troubled me, and

wherefore I had cried to thee:

What thing I longed for to appease my frantic

Soul; and whom now must I persuade, thou askedst,

Whom must entangle to thy love, and who now,

Sappho, hath wronged thee?

Yea, for if now he shun, he soon shall chase thee;

Yea, if he take not gifts, he soon shall give them;

Yea, if he love not, soon shall he begin to

Love thee, unwilling.

Come to me now too, and from tyrannous sorrow

Free me, and all things that my soul desires to

Have done, do for me, queen, and let thyself too

Be my great ally!

Symonds, 1877

Star-throned incorruptible Aphrodite, Child of Zeus, wile-weaving, I supplicate thee, Tame not me with pangs of the heart, dread mistress, Nay, nor with anguish. But come thou, if erst in the days departed Thou didst lend thine ear to my lamentation, And from far, the house of thy sire deserting, Camest with golden Car yoked: thee thy beautiful sparrows hurried Swift with multitudinous pinions fluttering Round black earth, adown from the height of heaven Through middle ether: Quickly journey they; and, O thou, blest Lady, Smiling with those brows of undying lustre, Asked me what new grief at my heart lay, wherefore Now I had called thee, What I fain would have to assuage the torment Of my frenzied soul; and whom now, to please thee, Must persuasion lure to thy love, and who now, Sappho, hath wronged thee? Yea, for though she flies, she shall quickly chase thee; Yea, though gifts she spurns, she shall soon bestow them; Yea, though now she loves not, she soon shall love thee, Yea, though she will not! Come, come now too! Come, and from heavy heart-ache Free my soul, and all that my longing yearns to Have done, do thou; be thou for me thyself too Help in the battle. Symonds, 1883

In general, this poem shows Sappho’s prayer to Aphrodite for her love toward another woman, along with Aphrodite’s response. The 6th stanza of the poem, which I highlighted, is Aphrodite’s respond to Sappho saying her love shall be accomplished. In the 1877 translation, the pronoun is “he,” or masculine, while in the 1883 translation, the pronoun is “she,” or feminine.

What does this change mean? To begin with, the gender of the pronoun (αί) is feminine. However, many scholars translated this pronoun as masculine. This can be also seen in Wharton’s Sappho, where every translator who translated this fragment used masculine pronoun in 6th stanza. It was only Symonds, in his 1883 edition, who followed the gender of original poem.

Meanwhile, this change of pronoun suggests that Symonds is also viewing Sappho’s love as homosexual. At first he also followed others and used masculine pronoun in 6th stanza, stating Sappho’s lover as male. However, by changing pronoun to feminine, he boldly stated that Sappho’s lover is female, and that she is expressing homosexual love.

Indeed, in his famous A Problem in Greek Ethics Symonds also mentions Sappho and Lesbian poets:

“It is true that Sappho and the Lesbian poetesses gave this female passion an eminent place in Greek literature. But the Aeolian women did not found a glorious tradition corresponding to that of the Dorian men. If homosexual love between females assumed the form of an institution at one moment in Aeolia, this failed to strike roots deep into the subsoil of the nation.”

Symonds A Problem in Greek Ethics 78

Here, Symonds views Sappho and her companions as potentially an example of female homosexuality. While he admits that female homosexual love was not as developed as male homosexual love in Greek, as its tradition did not continue, Symonds indeed considers Sappho and her Lesbian poets as outliers in the general trend of Greek love.

Finally, both Wharton and Symonds express their interest in Sappho’s talent in her poems. In his book, Wharton describes how ancient people appreciated Sappho’s poems. Many writers use the epithet “beautiful” for the sweetness of her songs (Wharton, 20). Likewise, Symonds expresses his pleasure of Lesbian poets in his Studies of the Greek Poets:

When we read their poems, we seem to have the perfumes, colours, sounds and lights of that luxurious land distilled in verse. […] The voluptuousness of Aeolian poetry is not like that of Persian or Arabian art. It is Greek in its self-restraint, proportion , tact. We find nothing burdensome in its sweetness.

Symonds Studies of the Greek Poets 138

Then Symonds especially comments on Sappho in:

All is so rhythmically and sublimely ordered in the poems of Sappho that supreme art lends solemnity and grandeur to the expression of unmitigated passion. The world has suffered no greater literary loss than the loss of Sappho’s poems. […] Of all the poets of the world, of all the illustrious artists of all literatures, Sappho is the one whose every word has a peculiar and unmistakable perfume, a seal of absolute perfection and inimitable grace. In her art she was unerring.

Symonds Studies of the Greek Poets 138-139

Ultimately, both Wharton and Symonds state that Sappho was called “The Poetess,” like Homer was “The Poet” (Wharton, 27 and Symonds, 138). By comparing Sappho to Homer, one of the most influential poets in Greek poetry, both Wharton and Symonds are stressing the importance of Sappho.

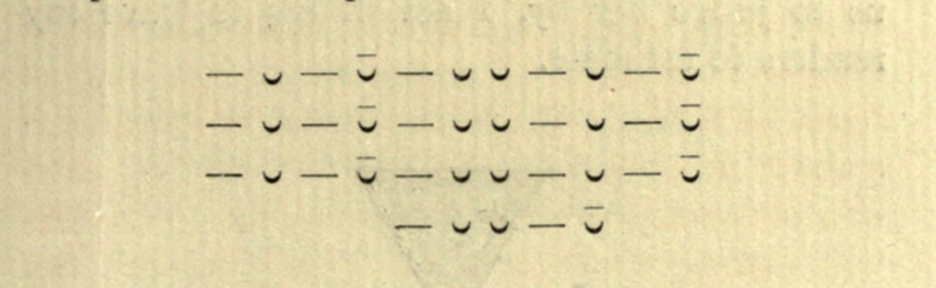

Among many aspects of Sappho, the one I find most significant is her usage of the Sapphic meter, which though Sappho probably did not invent it, gained its name from her frequent usage. Wharton also describes the strophe of the meter:

Wharton, Sappho 45

He then gives fragments of contemporary poet Algernon Swinburne’s Sapphics that follow Sapphic meter in English.

All the night sleep came not upon my eyelids,

Shed not dew, nor shook nor unclosed a feather,

Yet with lips shut close and with eyes of iron

Stood and beheld me.

Swinburne Sapphics 1866

While presenting Swinburne’s Sapphics, Wharton comments that these lines ring in the reader’s ear, and he can almost hear Sappho herself singing (Wharton, 46). Here, Wharton suggests a sense of her voice preserved in another person’s poem in another language by following her meter.

This was the part where I was fascinated because, indeed, a poem is not only about words but also rhythm. Considering this, reintroducing Sappho’s poem in English is introducing content and the rhythem at the same time which, in sum, reconstructs her memory.

Symonds also uses the Sapphic meter in his translation of Sappho’s fragment. One example would be Sappho’s fragment 1, which I presented earlier. With this, Symonds also attempted to maintain Sappho’s memory, just as he preserved Cellini and Gozzi’s memory by translating their memoirs.

In his Memoirs, Symonds said his work with Cellini and Gozzi motivated him to write his own memoir (Memoir, 1). Though Symonds only credits Cellini and Gozzi, it is possible that Sappho could be seen as another motivator.

Works Cited

Sappho., Wharton, H. Thornton. (1887). Sappho: memoir, text, selected renderings and a literal translation. 2nd ed. London: D. Stott.

Symonds, John Addington. (1877). Studies of the Greek poets. 2d ed. London: Smith Elder.

Symonds, John Addington. (1883). A Problem in Greek Ethics.

Symonds, John Addington. (2016). The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition, (Amber K. Regis, Ed.). Palgrave Macmillan Publishing. London.

Swinburne, A. Charles. (1866). Poems and ballads.. London: John Camden Hotten, Piccadilly.