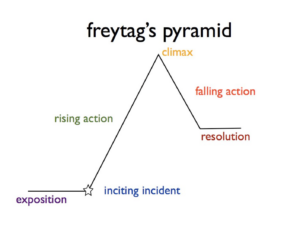

We’ve all probably faced many “accidents” in life, whether it’s Hurricane Helene or a chance encounter. In fact, even being born into this world can be considered an accident, just as George Moore writes in his semi-fictitious memoir The Confessions of a Young Man, “The accident of birth rather stimulated than calmed my erubescent admiration” (25). An accident as grand as birth can have an impact as big as life, but if not, it can at least lead to a story, serving as a natural “inciting incident,” which, you’ll know if you’re familiar with Freytag’s Pyramid, marks the beginning of a story.

That said, let’s take a step back because the following story begins with the accident of me coming across The Confessions of a Young Man in John Addington Symonds’s virtual library. What would you find in Symonds’s library? Naturally, as a classicist, poet, and literary critic, Symonds would have read many books on poetry, literature, and ancient Greece and Rome. But he also wrote a memoir in the final years of his life. So, I thought, he must have read other memoirs too, and I wanted to read a memoir that Symonds had read, other than the two of great importance to him, the memoirs of Benvenuto Cellini and those of Carlo Gozzi… Then, among the hundreds of books in his library, I came across The Confessions of a Young Man, which is a memoir written in the name of a first-person narrator named Dayne. And the narrator is a struggling artist, like me! So I decided to read this book.

The plot is simple: Dayne, a defiant, spoiled young man from a wealthy Irish family, goes to Paris to study art, only to realize he lacks talent. But what makes him want to study art in the first place is just a brief exchange with a stranger he meets in a studio in London.

“‘How jolly it would be to be a painter,’ I once said, quite involuntarily. ‘Why, would you like to be a painter? ‘ he asked abruptly. I laughed, not suspecting that I had the slightest gift, as indeed was the case, but the idea remained in my mind, and soon after I began to make sketches in the streets and theatres” (Moore, 9).

The idea is planted in Dayne’s mind, though he’s slow to act, being quite incompetent—even his father’s death isn’t an accident significant enough to prompt an immediate change in his idle, good-for-nothing lifestyle. And such is the logic of Dayne’s life: full of chance encounters. When he finally makes it to Paris, he runs into the same man he met in London again—who, by coincidence, joins the same studio where Dayne’s been studying. His name is Marshall, whom Dayne befriends. And the chance encounter doesn’t have to be with a person—it could just as easily be with a new idea. While waiting at a café for his writer friend, Dayne picks up the newspaper Le Voltaire, where he reads an article by M. Zola on naturalism, an approach to writing that challenges what he’s always believed.

“Hardly able to believe my eyes, I read that you should write, with as little imagination as possible, that plot in a novel or in a play was illiterate and puerile, and that the art of M. Scribe was an art of strings and wires, etc. I rose up from breakfast, ordered my coffee, and stirred the sugar, a little dizzy, like one who has received a violent blow on the head” (Moore, 112-113).

The thing is, Symonds experiences a similar awakening! On a trip to London during his last year at Harrow, he took his required reading—Cary’s Plato—with him, but instead of reading the Apology as assigned, he “stumbled on the Phaedrus […] read on and on [and] began the Symposium” (JAS, Memoirs, 152). Through these two texts, Symonds starts to understand and come to terms with the confusion of his feelings—his love for “a handsome, powerful boy called Huyshe,” “Eliot Yorke,” and many others (151). He describes this unexpected discovery of Plato as something “of great gravity […] as though the voice of [his] own soul spoke to [him] through Plato, as though in some antenatal experience [he] had lived the life of a philosophical Greek lover” (152).

But is it really a chance discovery? Apology and Symposium aren’t in the same volume of the edition he describes, so unless Symonds purposefully brought both volumes with him, how could he read the Symposium if he only had the volume containing the required Apology (Butler, 214)?

Symonds probably did read George Moore, as it’s in his library. I’m not suggesting that Symonds plagiarizes or borrows from Moore; maybe he does, but that’s not the point here because using an accident as a plot device is nothing new in literature. The real question is, why does the writer make this creative choice? For George Moore, accidents are a recurring motif that aligns with the characterization of a tragic hero who fails to take responsibility for his life. Slow to realize that he lacks talent in both painting and writing, Dayne ultimately acknowledges this truth but doesn’t give up. Instead, he contemplates “[shooting] a man for the sake of the notoriety it would bring,” because if he can’t achieve fame and success positively, he’ll seek a destructive way to achieve something similar (Moore, 350).

Symonds isn’t as unreliable a narrator as Dayne, but he does recount an event that isn’t logistically possible, which could just be a case of misremembering. Perhaps he brings both volumes of Plato’s works. Perhaps he reads the Symposium in a different context. Or perhaps his discovery of Greek love isn’t entirely accidental. Instead, he may have been wanting—and even plotting—to read Phaedrus and Symposium, but the particular social and political context forces him to lie. We can never know for sure. What we do know is that Symonds chooses to frame his discovery as a chance encounter, something that simply happens to him, and he embraces it, even becoming fascinated by it.

Imagine a version of the story where this plot point happens later in Symonds’s life, when he has a clearer awareness of his desires and actively seeks to understand them through literature, from classical to modern, in hopes of finding someone who shares his experiences. In this version, Symonds, as the speaker in his memoir, would have more control over what he reads. However, Symonds, the writer of the memoir, chooses to present it all as an accident, framing the discovery as something beyond the control of the constructed self on the page. By doing so, Symonds, the writer, manages to create an interesting tension between having and not having agency at the same time. As the writer, he has the power to decide which version of the story to tell but ultimately chooses the one where the speaker lacks much agency.

And homosexuality, for a long time, has been like this: the need to hide one’s identity and contain desire while still being driven to act on it—whether through cruising, where one has to deliberately go to a certain area, or through more intellectual exchanges to feel out a potential connection. In fact, Symonds did both, as his memoirs mention hooking up with a sailor, and his letters reveal how he would ask others about their thoughts on queer literature to see if they might be queer like him.

Works Cited

Butler, Shane. The Passions of John Addington Symonds. Oxford University Press, 2022.

Moore, George, 1852-1933. Confessions of a Young Man. London: Swan Sonnenschein & co., 1888.

Symonds, John Addington, and Amber K Regis. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.