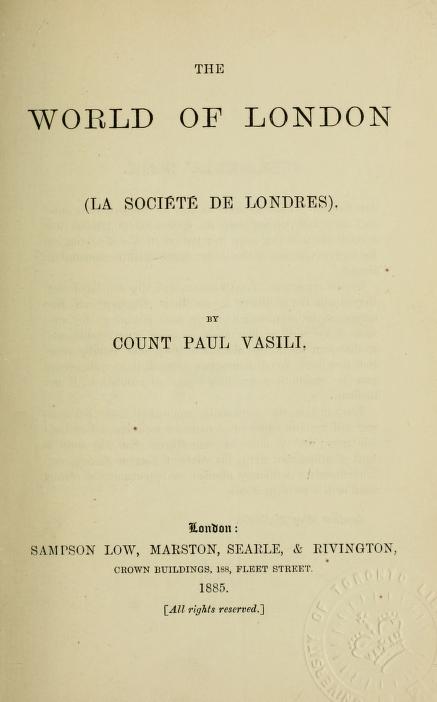

Understanding the social, economic and political conditions of John Addington Symonds’ life is crucial to understanding his personality and his writing. It is also a way to find the connections he had with other writers and translators. The World of London represents an opportunity to deepen this dimension we may have ignored so far. This book clearly belonged to Symonds’ library with an entry in William George’s Sons 1909 catalog (see lost library). The World of London describes British society around 1885 through a series of 25 letters written by Count Vasili. It gives information about how British politics worked, how the gentry and the aristocracy lived or how sports was a structuring activity for Englishmen. It also describes the important political leaders, statesmen, scientists, and writers. It is designed for someone who does not live in London, the capital city of the United Kingdom, but still wants to understand British civilization.

First, I will focus on the history of The World of London, its author and the edition Symonds may have read. Then, I will connect this book to other volumes that may have belonged him but were not in William George’s Sons catalog of 1909.

The catalog doesn’t contain detailed information on the version Symonds owned. The most valuable information is the date of publication (1885) which indicates that Symonds was already an accomplished author and gentleman when he read The World of London. I assume he owned an English edition and the only possibility was the one published by Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. It is worth noting that in both the American and English editions of the book, there is an interesting introductory note. It explains that the publishers did not see any part of the text before publication. However, they reserved the right to remove some passages if they thought they were “too scandalous, if not libelous” (page II). It is probably because some quite sarcastic letters in the book criticize the Royal Family, politicians and British Society more generally. A non-expurgated French edition is available online and includes 28 letters instead of 25 for the English edition.

The World of London was not written by a British author. The book was initially published in France by Comte Paul Vasili, an alleged Russian aristocrat. In fact, Paul Vasili was a pseudonym for a group of writers that included Juliette Adam, Catherine Radziwill and others. It is not really clear if the book has been mostly written by Adam or Radziwill. The non-British author is a reason why this book gives perhaps obvious details about English culture. It was also purportedly written for non-British readers who may need some basic knowledge about British Society. An English gentleman like Symonds would likely have read this book to understand how a foreign author saw British culture. He may not have paid attention to the elements he already knew. I had the opposite approach because the details about British society were crucial in my attempt to understand the historical context surrounding Symonds and his library.

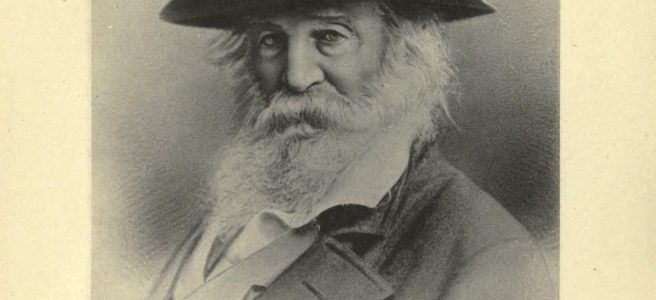

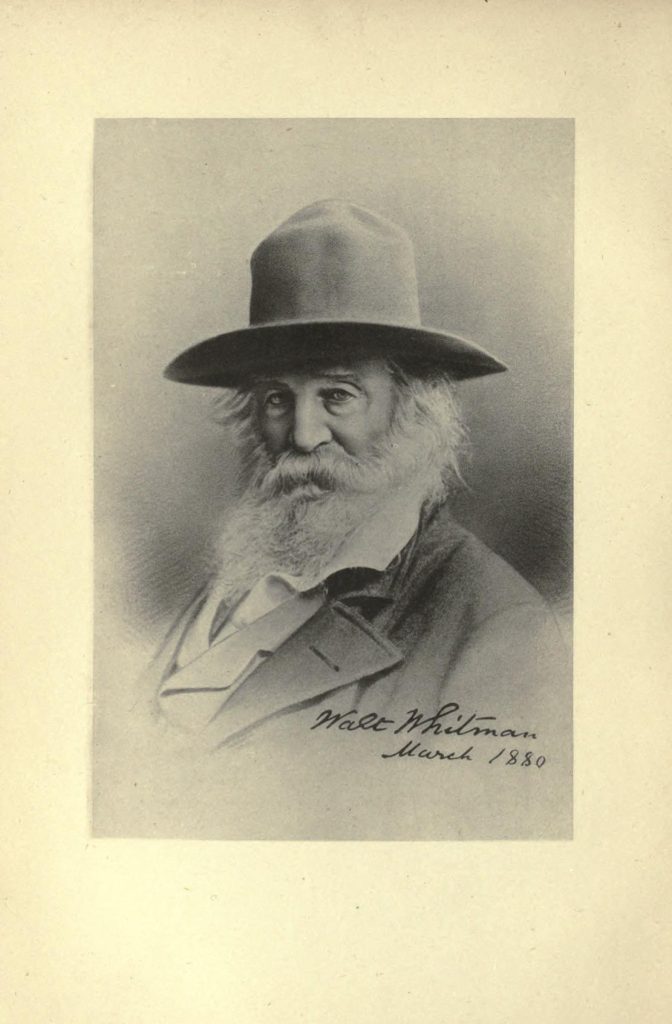

The World of London contains many chapters focused on politics, a subject that we have not extensively discussed so far. It is an opportunity to find new leads about his library. Symonds did not write about ordinary politics (elections, parties, etc.) in his Memoirs. He explained that his father was close to the Liberals (“He corresponded with the leading Liberals in politics, religion, and philosophy.”, page 84) but Symonds did not mention his own views. The words “vote”, “politics” or “elections” are almost absent when searching the Memoirs but there are other clues about his opinions. For instance, The World of London tends to be in favor of Liberals than any other party. Furthermore, Symonds was related to T.H. Green who influenced the social-liberal movement. He was also a friend with Edward Carpenter who was openly socialist. Therefore, Symonds was arguably a liberal and British scholar Colin Tyler considers he was even close to “an eroticized form of democratic socialism.” (J.A. Symonds, socialism and the crisis of sexuality in fin-de-siècle Britain, History of European Ideas, 2017). It is close to the conception I in my previous post on Walt Whitman: a study. Symonds’ library should reflect his political thoughts. Publications from Edward Carpenter are already in our database but there is nothing about Green. We should expect to discover some books written by this author and more generally volumes about political theory in subsequent researches

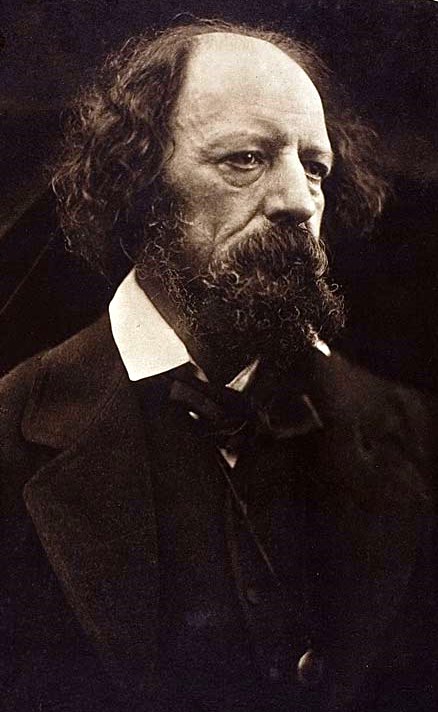

The World of London helps us understand which poets and/or novelists were prominent around 1885 and many poets mentioned in this book were on Symonds’ shelves. Even if Symonds was proud of his collection of Walt Whitman’s books, Whitman was not, by any mean, the only poet he read. For instance, The World of London has information about Lord Tennyson, the Poet Laureate. We know Tennyson was an author Symonds read because there are two entries in our catalog under this name. Robert Browning follows the same pattern. Vasili mentioned him and Symonds owned three of his books. However, there is no record of the other eminent authors mentioned in by Vasili. Books by George Eliot, Charles Dickens and John Stuart Mill were presumably on Symonds’ shelves even if there is no record. These missing titles make it very clear that the bookseller’s catalog we are using to reconstruct the library is not exhaustive. A significant amount of work still needs to be achieved to fully comprehend the composition of Symonds’ library.

In conclusion, The World of London is interesting because it relates to the society surrounding Symonds. As a part of the intellectual élite, Symonds cannot be detached from a political situation that includes the reign of Queen Victoria, reforms and modern political thinkers. The rise of some poets and successful authors of novels may have also affected Symonds. In the end, The World of London represents an opportunity to identify books we may find are important in our further attempts to reconstruct his lost library.

Works cited and useful links:

Colin Tyler (2017) J.A. Symonds, socialism and the crisis of sexuality in fin-de-siècle Britain, History of European Ideas, 43:8, 1002-1015, DOI: 10.1080/01916599.2017.1284141

Quinn, J., & Brooke, C. (2011). ‘Affection in Education’: Edward Carpenter, John Addington Symonds and the politics of Greek love. Oxford Review of Education, 37(5), 683–698. DOI: 10.1080/03054985.2011.625164

Regis, Amber K. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

Symonds, John Addington. Walt Whitman: a Study. London: G. Routledge & sons, limited, 1893. (link)

Vasili, P., Cyon, E. de, & Adam, J. (1885). The world of London : La société de Londres. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington. (Internet Archive / Hathi Trust)

Vasili, P., Cyon, E. de, & Adam, J. (1885). La société de Londres. Paris: Nouvelle Revue. Fourth Edition. (Internet Archive)

More information on T.H. Green (link)