Thank you very much for Job. It is a beautiful copy. I have compared it with my father’s, & find the proofs wh you have given me far finer than his impressions.”

Symonds, Letters, 1:506 (360)

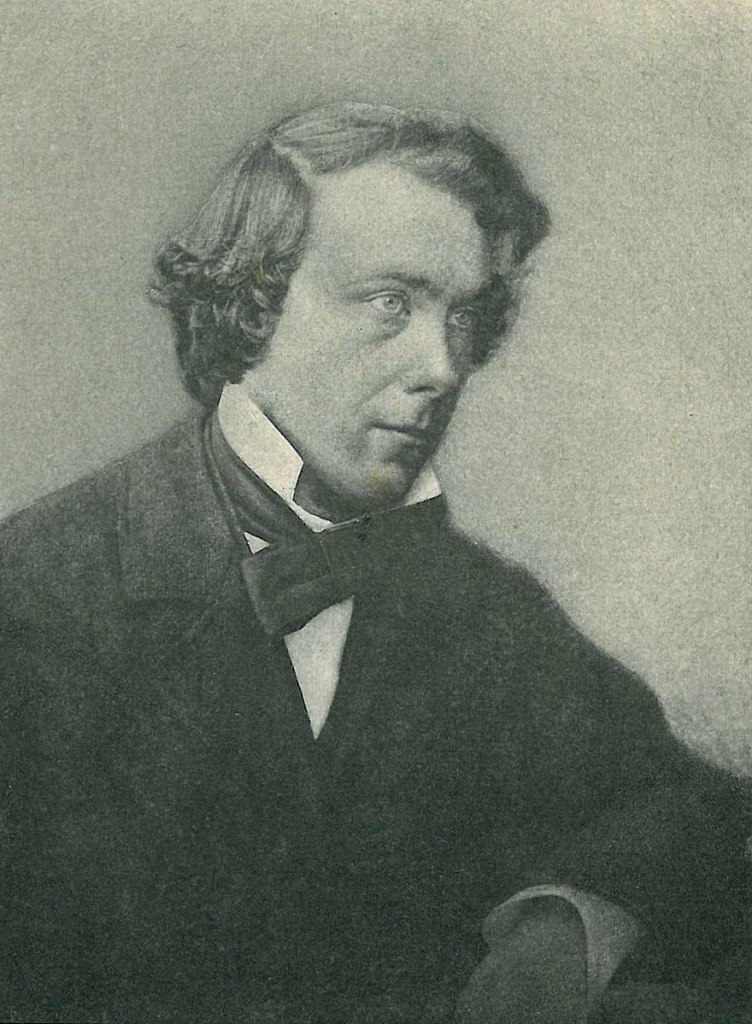

So John Addington Symonds wrote in a letter to his good friend Henry Graham Dakyns in November of 1864.

At first glance, it would seem that Symonds is referring to the Book of Job from the Bible. After all, that is certainly the best-known literary Job, and it would not be at all unusual for Symonds’s father to already have a copy. However, there is a possibility–albeit less likely–that Symonds here is referring to a poem entitled “Job the White.”

“Job the White” was written by T.E. Brown. Brown was best known for his long narrative poems written in the Manx dialect–the traditional dialect of the Isle of Man. The first poems in his series of Fo’c’s’le Yarns were published in 1881; “Job the White,” in the third and final book of the series, was not published until 1895. While this publication date, 30 years after Symonds wrote his letter to Dakyns, makes it unlikely that Symonds is referring to the poem, there nevertheless exists a deeper literary relationship between the two.

To begin with, Dakyns and Brown were good friends. Indeed, Brown even composed a poem addressed to Dakyns, entitled “Epistola Ad Dakyns,” which was published in his collection Old John and Other Poems.

DAKYNS, when I am dead,

Three places must by you be visited,

Three places excellent,

Where you may ponder what I meant,

And then pass on —

Three places you must visit when I’m gone.

Brown, “Epistola Ad Dakyns”

And while I do not know for sure whether Dakyns did visit these three places, he nevertheless played a part in perpetuating Brown’s legacy posthumously; Dakyns was one of the three editors of The Collected Poems of T.E. Brown.

More than just having a mutual friend in Dakyns, though, Symonds and Brown were themselves friends. In fact, the two shared unpublished poems with each other. While humble about his own poetry (describing it in one letter to Brown as “too diffuse & voluminously descriptive” (Letters, 2:118 (717))), Symonds was quite fond of Brown’s work.

Brown’s new poem is A…I do wish he would print one of his poems.”

Symonds, Letters, 2:119 (718)

It would be a decade before this wish would come true. Nevertheless, we can be certain that Symonds did indeed read Brown’s unpublished work; how closely those early versions resembled the final pieces we have in book form today is difficult to know.

After reading Symonds’s (posthumous) biography by Horatio Brown, T.E. Brown expressed some measure of surprise at the contents. In particular, he was struck by the relative prevalence of “agony,” while literary matters fell somewhat by the side. Symonds’s biography was largely based on his Memoirs, and thus his own priorities of his story; but there exist other lenses through which he can be understood, and they are not necessarily any less true. Brown’s image of Symonds–an image formed through years of friendship and swapping of literature–is one of these other angles. But at present, we have yet to reach a full understanding of the relationship between the two. It is not certain that the “Job” Symonds referred to in his 1864 letter is Brown’s–but, if that is indeed the case, it stands as a very early instance of their relationship being put to paper.

References:

Amigoni, David. 2009. “Translating the Self: Sexuality, Religion, and Sanctuary in John Addington Symond’s Cellini and Other Acts of Life Writing,” Biography 32, no. 1 (2009): 161–72.

Brown, T.E. 1893. Old John and Other Poems. London: Macmillan and Co.

Brown, T.E. 1909. The Collected Poems of T.E. Brown. Edited by H.F. Brown, H.G. Dakyns, and W.E. Henley. London: Macmillan and Co. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t6930zd83

Symonds, John Addington. 1967.The Letters of John Addington Symonds. Edited by Herbert M. Schueller and Robert L. Peters. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

“T.E. Brown.” Manx Literature. http://manxliterature.com/browse-by-author/t-e-brown/