Children’s books are, in a way, life guides for their impressionable readers. Being a source of knowledge other than closely related family and friends, these books are written to be relatable and inspirational. It is inevitable that hints of the philosophies that children’s books intend to teach remain influential in the children throughout their lives. Throughout John Addington Symonds’s first twenty-five years of life, a childhood tale, Hans Christian Andersen’s The Ugly Duckling, returned to his mind from time to time. Symonds used to “sympathized passionately with the poor bird swimming round and round the duck-puddle” (Memoirs, 67). Just as most children have empathized with the ugly duckling (for it is only typical and natural to believe in a destined happy ending), Symonds has likened himself to the ugly duckling for his inherent belief in his capability to establish his own place in the world.

From his childhood, John Addington Symonds demonstrated outwardly a bright activity, as substantiated by a letter from his sister’s Governess, Sophie Girard (Memoirs, 124). Nevertheless, to Symonds’s own perception, he was never one of spirited and congenial nature. “Being sensitive to the point of suspiciousness,” he constantly imagined that he “inspired repugnance in others,” most possibly due to his nervous character and “many physical ailments” (Memoirs, 67-68). This belief urged him to unconsciously dissemble his most intimate feelings and put on a common disguise.

Symonds’s development of personality greatly intertwined with his development of sexual consciousness. After the first revelation to the sexual sentiments by his nurse and fellows, Symonds realized through his early experiences that the “sex which drew [him] with attraction was the male”(Memoirs, 100). Since an early age, Symonds realized vaguely that the recurring reveries and dreams of robust and masculine men indicated some difference in himself. This awareness, accompanied by his distinct character, made him unlike his peers.

I felt that my course, though it collided with that of my schoolfellows, was bound to be different from theirs.

The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds, 134

Symonds’s experience can be compared side by side with that of the ugly duckling, in more ways that have been mentioned so far . In his Memoirs, Symonds describes his time (1854–58) at Harrow School for boys, as follows:

Living little in the open air, poring stupidly and mechanically over books, shut up for hours in badly ventilated schoolrooms and my own close study, I dwindled physically…It is no wonder that I came to be regarded as an uncomradely unclubbable boy by my companions.

The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds, 135-136

It would be preposterous to assert that Symonds has gained no respect or formed no friendships at Harrow, for he has devoted a portion of his Memoirs to portray these valuable experiences. However, it is reasonable to say that Symonds was not generally sociable during these four years, and that, like the ugly duckling, he was regarded by the majority of his peers as feeble and different.

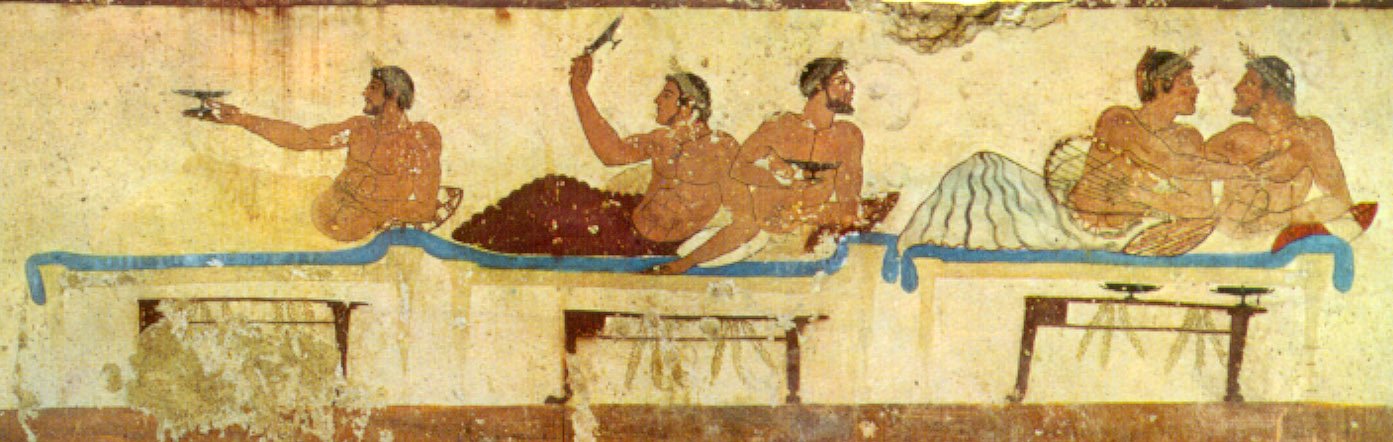

The years at Harrow School, though not all joyful, contributed to a phenomenal internal growth in Symonds. Close interactions with young boys of his age allowed him to explore and become more aware of his idea of sex. At the meantime, upon witness of daily obscenity in the dormitories and degrading treatment of “every boy of good looks” “either as public prostitute or as some bigger fellow’s ‘bitch,'” Symonds was filled with disgust for lustful and obscene characters (Memoirs, 147). More than once has Symonds mentioned the influence that the Greek in him has brought to his aesthetics and conduct of life. Even before reading much of Greek literature, he had, he claims, “an ideal passion which corresponded to Platonic love” (Memoirs, 149).

In Symonds’s first mention of The Ugly Duckling, he explains what moved him greatly in the story:

I cried convulsively when he flew away to join his beautiful wide-winged white brethren of the windy journeys and the lonely meres.

The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds, 67

In the Memoirs, the night when Symonds read Plato’s Phaedrus and Symposium can be juxtaposed in importance to the time when the ugly duckling fledged into a beautiful swan. Despite the fact that he was born in 19th century England, Symonds was not granted a sense of belongingness to his own surroundings, partly because his sexual orientation could not be discussed or professed publicly without him being criticized by contemporaries. Instead, he was able to reconcile himself with Greek literature from over two thousands years ago:

For the first time I saw the possibility of resolving in a practical harmony the discords of my inborn instincts.

The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds, 152

The good creature felt himself really elevated by all the troubles and adversities he had experienced. He could now rightly estimate his own happiness, and the larger swans swam around him, and stoked {check} him with their beaks.

Danish Fairy Legends and Tales, 42

It is remarkable that this children story had such a great impact in Symonds that the ugly duckling is mentioned even in recollection of his university life. In Chapter 6 of the Memoirs, which speaks of his life in the University of Oxford, Symonds recounts once more how he “was still the ugly duckling”, because he was sustained by “a dim consciousness of latent ability” (171). This feeling reflects that from his childhood, and presumably it lasted beyond his youth.

Symonds’s academic and personal connection to Greek literature led to his deeper studies about Greek society and works. While John Addington Symonds grew to be full-fledged as a translator and an author, he also achieved self-discovery and remained loyal to a sentiment that he believed to be antenatal:

My soul was lodged in Hellas.

The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds, 155

WORKS CITED:

Symonds, John Addington. Regis, Amber K. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Andersen, Hans Christian. Danish Fairy Legends and Tales. London: William Pickering, 1846

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hwhmbe