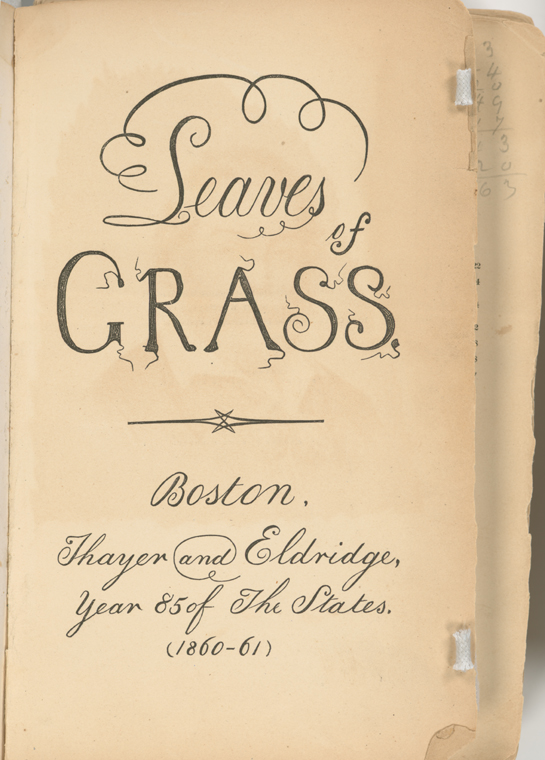

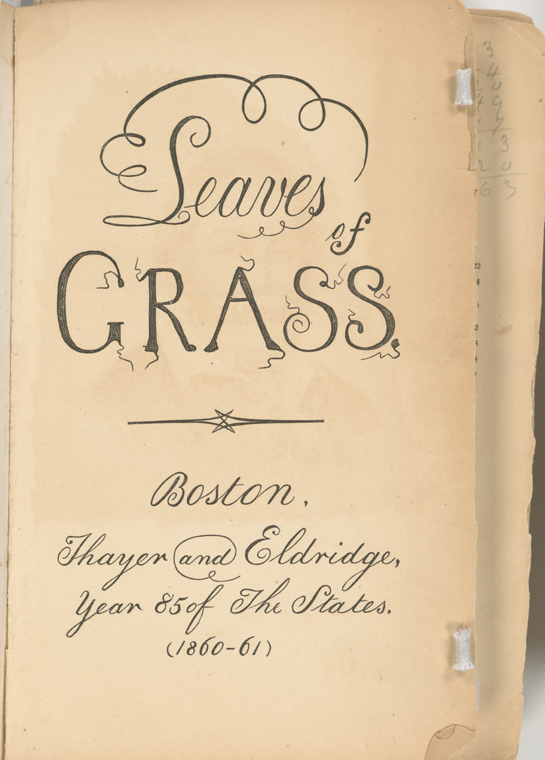

John Addington Symonds exchanged many letters throughout his life with American poet Walt Whitman. He records his first interaction with Whitman’s Leaves of Grass with fervor: “The book became for me a sort of Bible… I … tried to invigorate the emotion I could not shake off by absorbing Whitman’s conception of comradeship” (Memoirs, 368). The idea of comradeship is something that continued to permeate Symonds’ interaction with Whitman.

Through correspondence between Whitman and Symonds, we can see that Symonds used Leaves of Grass specifically as a catalyst for his interaction with an expanding community of interlocutors. In January of 1877, Symonds wrote to Whitman,

“I do so now [i.e., write you], however, begging you to send me copies of Leaves of Grass & Two Rivulets… I shall then have copies for myself & copies to give to a friend.”(1)

This letter shows us that Symonds is beginning to expand his social circle using Whitman’s poetry. Throughout the next few years, Symonds continued to write to Whitman, developing an infatuation with the poet and his work. Through these letters we see that Symonds uses the writings as a means to interact with the kind of people to whom Whitman refers in “In Paths Untrodden” as “all who are, or have been, young men.” (2)

In June of 1886, Whitman wrote to Symonds, “I write a line to introduce & authenticate a valued personal & literary friend of mine, Wm Sloane Kennedy, who will send you this. He is every way friendly & [sic] rapport with ‘Leaves of Grass’ & with me.” (3) Whitman is responsive to Symonds’ sentiment and widens the circle of men bonding over Leaves of Grass. Within Symonds’ world this collection of poems becomes a way to unite people across countries and continents. Perhaps for Symonds this meant feeling less alone as he thinks about his sexuality.

Leaves of Grass is a way to make new connections as well as to deepen already established relationships. Symonds tells Whitman that, “I gave him [Symond’s nephew] a copy of Leaves of Grass in 1874, & he knows a great portion of it now by heart.” (4) Symonds also included some of his nephew’s poetry in the letter. The collection allows Symonds to share a sort of emotional vulnerability with people. Symonds clearly hoped that the people with whom he chose to share the poet’s words would interpret the words as he had. Symonds thus allows Whitman’s words to express his own feelings.

Symonds’ equating of Leaves of Grass to the Bible reveals that, in a way, he uses the collection as some use religious texts. It is a medium by which to spread a message and create a community. Symonds specifically cites the “Calamus” cluster of poems. He writes, “Inspired by ‘Calamus’ I adopted another method of palliative treatment, and tried to invigorate the emotion I could not shake off by absorbing Whitman’s conception of comradeship,” (Memoirs, 368) this last word being the term Whitman used and Symonds adopted as a kind of code for male-male attachment. It may have been this idea that prompted Symonds to do his best to connect with as many men as possible through the text. The poem, “In Paths Untrodden” in particular would likely have resonated with Symonds:

“That the soul of the man I speak for, feeds, rejoices only in comrades…

I proceed, for all who are, or have been, young men,

To tell the secret of my nights and days,

To celebrate the need of comrades.”(5)

Symonds’ interaction with Leaves of Grass provides us the ability to understand how he used the text to create a community. It is undeniable that the collection of poems is something profound that Symonds wishes to share.

Footnotes:

(1) “John Addington Symonds to Walt Whitman, 23 January 1877.” The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. Accessed 14 October 2019. <https://whitmanarchive.org/biography/correspondence/tei/loc.04208.html>.

(2)Whitman, Walt. “In Paths Untrodden.” Leaves of Grass, Whitman Archive, 1860-1861. <https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1860/poems/77>.

(3) “Walt Whitman to John Addington Symonds, 20 June 1886.” The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. Accessed 14 October 2019. <https://whitmanarchive.org/biography/correspondence/tei/loc.04965.html>.

(4) “John Addington Symonds to Walt Whitman, 12 July 1877.” The Walt Whitman Archive. Gen. ed. Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. Accessed 14 October 2019. <https://whitmanarchive.org/biography/correspondence/tei/loc.04063.html>.

(5) Whitman, Walt. “In Paths Untrodden.” Leaves of Grass, Whitman Archive, 1860-1861. <https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1860/poems/77>.

Works Cited:

Symonds, John Addington. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Edited by Amber K. Regis, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

“The Walt Whitman Archive.” Edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, The Walt Whitman Archive, whitmanarchive.org.