While reading his Memoirs, I was particularly interested in the childhood of Symonds. We often think childhood memories are important because they lead to the development of character for the rest of our lives. Symonds also had this idea, writing in his Memoirs “No one, however, can regard the first stirrings of the sexual instinct as a trifling phenomenon in any life” (Symonds 99). While Symonds remained unsure about the ultimate origin of his (or anyone’s) sexual orientation, he thought that its ultimate form must have first taken in childhood. After reading the chapter about his childhood love, I wanted to further examine his childhood loves and how they contributed to his character in his later life.

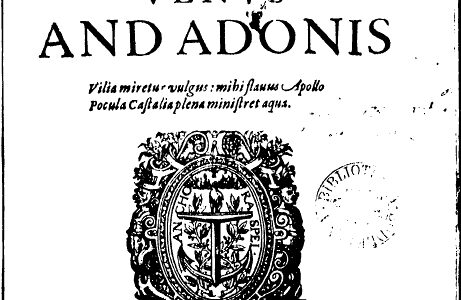

The first figure I would like to discuss is Adonis. In his Memoirs, Symonds discusses how he fell in love with Adonis by reading the poem Venus and Adonis by William Shakespeare.

“Now the first English poem which impressed me deeply—as it has, no doubt, impressed thousands of boys—was Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis […] Adult males, the shaggy and brawny sailors, without entirely disappearing, began to be superseded in my fancy by an adolescent Adonis. The emotion they symbolized blent with a new kind of feeling. In some confused way I identified myself with Adonis; but at the same time I yearned after him as an adorable object of passionate love. Venus only served to intensify the situation. I did not pity her. I did not want her. I did not think that, had I been in the position of Adonis, I should have used his opportunities to better purpose.”

Symonds Memoirs 101

I found Symonds’s love for Adonis interesting because he did not fall in love only with the physical beauty of Adonis but also with the beauty of the poem describing Adonis. From this, I was easily able to find one impact love for Adonis led to Symonds; Adonis sparked his love for the poem (and for poetry), which eventually helped to led him to become a poet himself. At the same time, Adonis is also figure from Greek myth, so it would have contributed to his becoming a classicist.

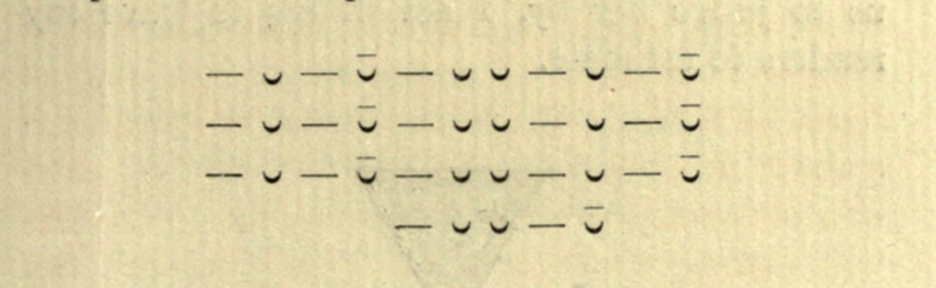

At the same time, as Symonds himself admitted, there was a dual sense of his love toward Adonis. He identified himself with Adonis, but he pursued Adonis at the same time. In the perspective of Greek love, Adonis would be the perfect example of eromenos, the “beloved.” The problem is that Symonds was too young to be the erastes, the “lover.” He rather fits the profile of the eromenos, which is why he partly identifes with Adonis. Maybe that’s why the feeling for Adonis was complex for Symonds, as if he knew he had to be eromenos from the perspective of ancient Greek sexuality. Thus, by expressing his love toward Adonis and identifying with Adonis simultaneously, he is presenting himself as both erastes and eromenos.

After looking at Symonds’s love for Adonis, I became curious whether he looked for more sources for Adonis in his adulthood—in another poet’s poetry, for example. When I first searched for Adonis in the Lost Library, I was disappointed to find out that there weren’t any books with the title “Adonis.”. Then, our newly constructed Lost Library in Hathitrust allowed me to do a keyword search, and I found a total of 101 books that contain “Adonis” at least once. For example, in Essays on Poetry and Poets, Roden Noel discusses the pathetic fallacy—the attribution of human nature to non-humans—in Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis (Noel 34). Here, Noel thinks loving Adonis provides and example of the pathetic fallacy because in myth Adonis changed into a flower after his death. Similarly, Adonis’s name can be seen in the botanical dictionary, Alpine Flowers for English Gardens, as one of the flowers. Thus, Adonis frequently appeared even in Symonds’s adult life in many different forms.

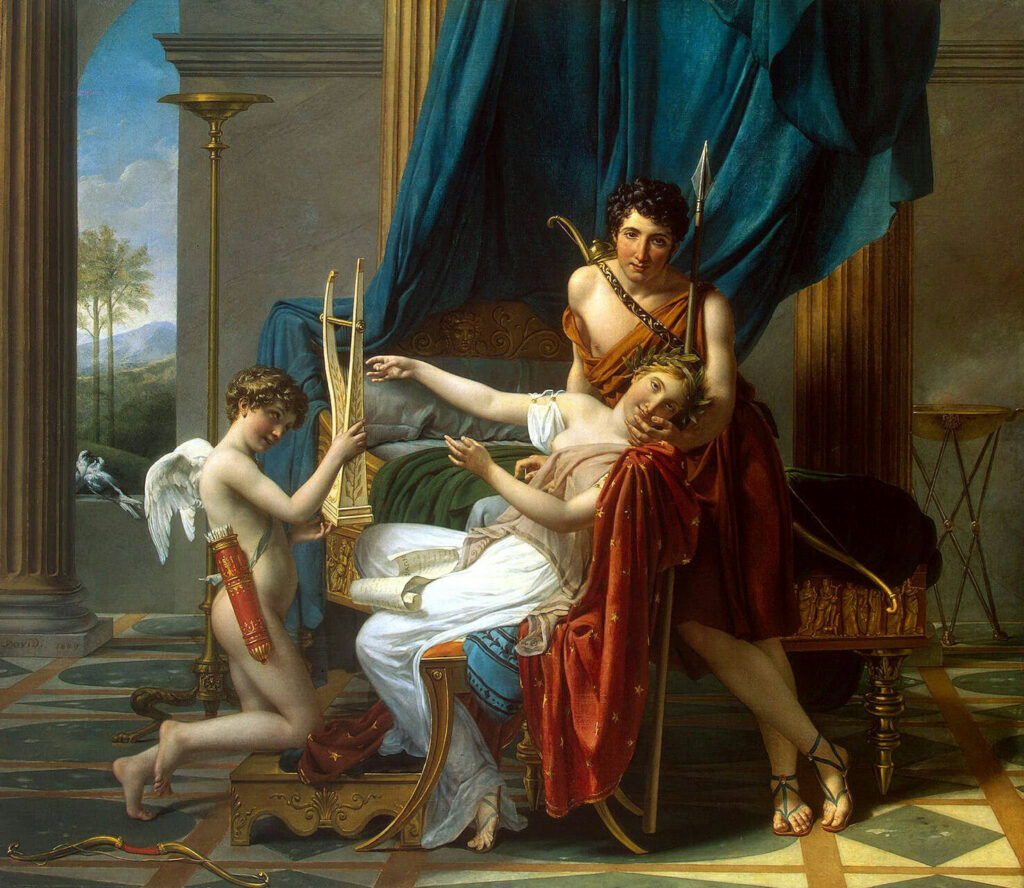

The other figure Symonds fell in love with is the statue of Cupid:

“A photograph of the Praxitelean Cupid: that most perfect of antiques They call the Genius of the Vatican, Which seems too beauteous to endure itself In this mixed world— taught me to feel the secret of Greek sculpture. I used to pore for hours together over the divine loveliness, while my father read poetry aloud to us in the evenings.”

Symonds Memoirs 118

Once again, it was straightforward to find the connection of love for Cupid to Symonds’s later life. Picture of the statue of Cupid allowed him to find interest in statues, and artworks in advance. Cupid is also a Classical figure, so it further sparked his interest in Classics. Thus, along with Adonis, Cupid might have motivated Symonds to study Classics.

Then, there is a question of whether Symonds actually saw this photograph in his childhood. Shane Butler, in The Passions of John Addington Symonds, points out the earliest photograph of Cupid was taken between 1855 and 1859, which is after the time Symonds claimed he saw the photo (Butler 208).

If we think Symonds fell in love with the statue of Cupid as an adult, this would fit into Greek pederasty by having Symonds as erastes and Cupid as eromenos. However, that does not seem to be the intention of Symonds. As he already did in the case of Adonis, he is presenting himself as erastes in his childhood. With this, he is emphasizing that his love for male youth occurred before he became an adult.

The final figure I would like to discuss is actually Symonds’s earliest but most peculiar love: his erotic vision of naked sailors.

“Among my earliest recollections, I must record certain visions, half-dream, half-reverie, which were certainly erotic in their nature, and which recurred frequently just before sleeping. I used to fancy myself crouched upon the floor amid a company of naked adult men: sailors, such as I had seen about the streets of Bristol. The contact of their bodies afforded me a vivid and mysterious pleasure. Singular as it may appear that a mere child should have formed such fancies, and unable as I am to account for their origin, I am positive regarding the truth of this fact. The reverie was so often repeated, so habitual, that there is no doubt about its psychical importance.”

Symonds Memoirs 100

This fantasy draws on something Symonds would have seen in his daily life, as he mentions that he regularly saw sailors on the streets of Bristol in his youth. At the same time, Symonds notes that this vision was “halfdream” and “half-reverie,” meaning this imagery was not exactly what he had seen. Thus, his imagery of naked sailors was the combination of what he actually saw in his daily life and his imagination.

From the perspective of Greek love, this fantasy of naked sailors seems problematic. Symonds as a boy was too young to be erastes, and sailors too old to be eromenoi. In fact, according to Greek love, it is Symonds who has to be eromenos and the naked sailor erastes. Also, the imagery of naked sailor has less connection with the other two figures he fell in love with: Adonis and Cupid.

Indeed, this vision of naked sailors could be seen as the outlier. He even admits that this vision “began to be superseded” by Adonis. At the same time, Symonds stresses the importance of vision of naked sailors by saying it happened often. He also says the vision did not entirely disappear even after he fell in love with Adonis (Symonds 101). That’s why I looked at his adult life to see if his love for adult male re-emerges.

Then, reading a draft of my colleauge Rex Xiao’s blog allowed me to recall that Symonds fell in love with Angelo Fusato on his trip to Venice. In his Memoirs, Symonds describes Angelo Fusato when he first met him:

“He was tall and sinewy, but very slender—for these Venetian gondoliers are rarely massive in their strength. Each part of the man is equally developed by the exercise of rowing; and their bodies are elastically supple, with free sway from the hips and a Mercurial poise upon the ankle […] Short blond moustache; dazzling teeth; skin bronzed, but showing white and delicate through open front and sleeves of lilac shirt.”

Symonds Memoirs 513-514

Some characteristics of Angelo Fusato, tall and sinewy but slender, are characteristics of Greek youths. Angelo Fusato was also younger than Symonds. Meanwhile, Angelo Fusato had mustache, which is against Greek youth as they are beardless or just began to have their beard growing. t is also interesting to see that Angelo Fusato’s occupation was gondelier, so there is loose connection with sailor. Given this, his fantasy toward an adult male reappeared when he fell in love with Angelo Fusato, but com, combined with his love toward youth.

After examining three fantasies of Symonds in his childhood to adolescence, I found unique common aspects. Symonds’s love, as he describes it, was primarily directed at the beauty of the male body. It is also interesting that all three figures were out of reach. Likewise, it is important to note that he fell in love with the statue of Cupid from the photograph, so he was not able to actually touch the statue of Cupid (much less Cupid himself). Even imagery of naked sailors is half-manipulated, and they appeared in half-dreams.

What would this mean? For one, I think this shows that Symonds’s desires were strongly visual, described in terms of privilege watching rather than doing. For instance, he leaves a comment after he mentions one incident when he watched a handsome boy masturbating in his presence:

“The attractions of a dimly divined almost mystic sensuality persisted in my nature, side by side with a marked repugnance to lust in action, throughout my childhood and boyhood down to an advanced stage of manhood.”

Symonds Memoirs 100

For one, this might be because he was too young to understand sexual intercourse. However, in his later adolescence period in Harrow, he hated the sexual relationship between male students. Probably this rejection of sexual action was already present in his childhood and developed in his adolescence. Thus, it may be no coincidence that several of the figures he loved were seen from afar.

Works Cited

Butler, Shane. (2022). The Passions of John Addington Symonds. Oxford University Press.

Noel, R. (1886). Essays on poetry and poets. London: K. Paul, Trench & Co..

Robinson, W. (William)., Bailey, W. Whitman. (1879). Alpine flowers for English gardens. 3d ed. London: Murray.

Symonds, John Addington. (1883). A Problem in Greek Ethics.

Symonds, John Addington. (2016). The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical

Edition, (Amber K. Regis, Ed.). Palgrave Macmillan Publishing. London.