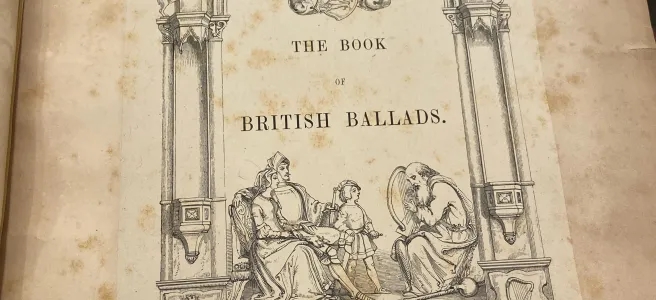

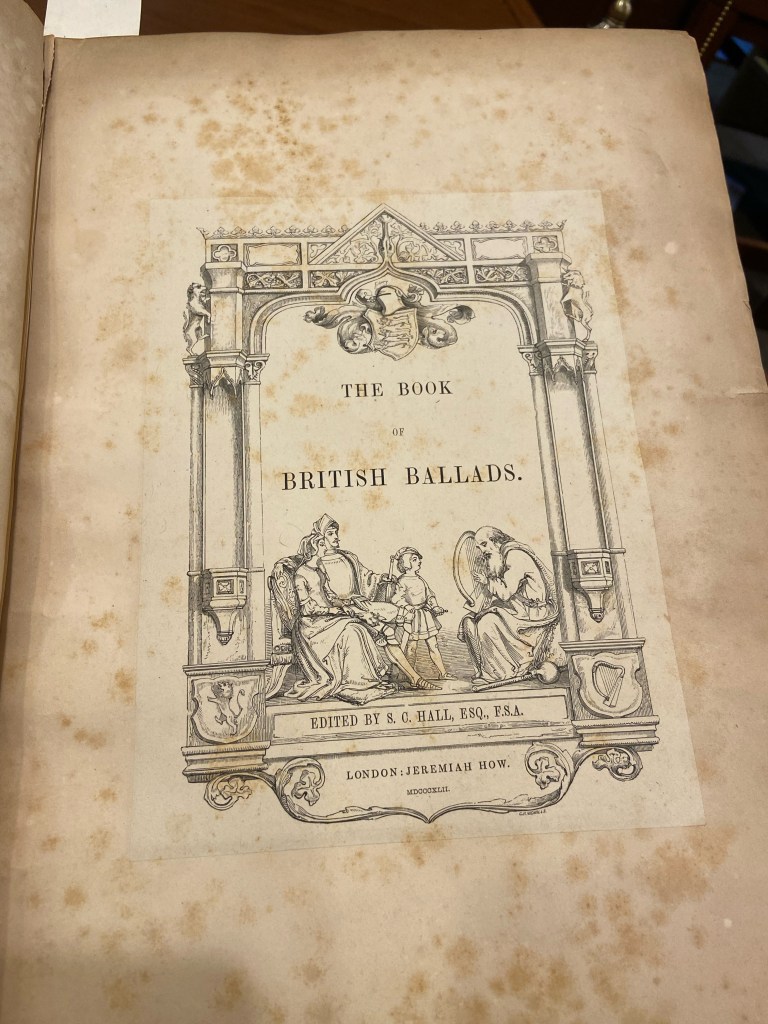

In his childhood, John Addington Symonds constantly suffered from “spiritual terrors” (Memoirs, 71). He identified several works that took hold of his imagination, including “a book of old ballads in two volumes” (ibid.). A copy of one likely candidate, The Book of British Ballads (edited by S. C. Hall and published between 1842 and 1844), is in the Special Collections of Johns Hopkins University’s library. When I first saw the book, my first instinct was to search for the pictures for three specific ballads Symonds mentions––“Glenfinals,” “The Eve of St John,” and “Kempion”––because they had brought emotional distress to young Symonds and had left him with deep impressions which were so long-lasting that he could clearly recall the exact names of all three ballads when he wrote his memoirs in his 40’s (ibid.). However, I only saw “Kempion” in the index and soon realized the book in our library was one of two published volumes.

In fact, the book in our library does not appear to be an original version, because it is obvious that the pages were removed from the original book and pasted on larger-sized pages (see the image below).

Also, near the end of this book, I observed the traces of several torn pages. Therefore, I suspected that the book in hand was not complete.

By referring to a digital version of the first volume of The Book of British Ballads, I discovered that the current version in our library leaves out a page from the original book with the text, “A SECOND SERIES OF THIS COLLECTION IS IN PROGRESS, AND WILL BE COMPLETED BY CHRISTMAS, 1843.” Therefore, I searched for the second volume of The Book of British Ballads online and discovered that the second volume had the complete index to the whole collection (both volumes), which includes all three ballads that Symonds mentions. “Glenfinals” and “The Eve of St. John” are in the second volume. Given that Symonds was born in 1840, the publication date, paired with Symonds’s explicit description of the book “in two volumes,” makes it a plausible candidate for the book of old ballads that evoked horrible imaginings in his young self, though he misremembers Daniel Maclise as one of the illustrators to this book (Memoirs, 92). (A Maclise illustration was used as the frontispiece to a later edition published in 1879, but not in the original volumes.) Finally, I managed to put together all the pictures in an attempt to find what they share and why they may have made Symonds “uncomfortable” (ibid.). Due to Symonds’s preoccupation with “spiritual terror,” my analysis will focus on analyzing pictures with supernatural components.

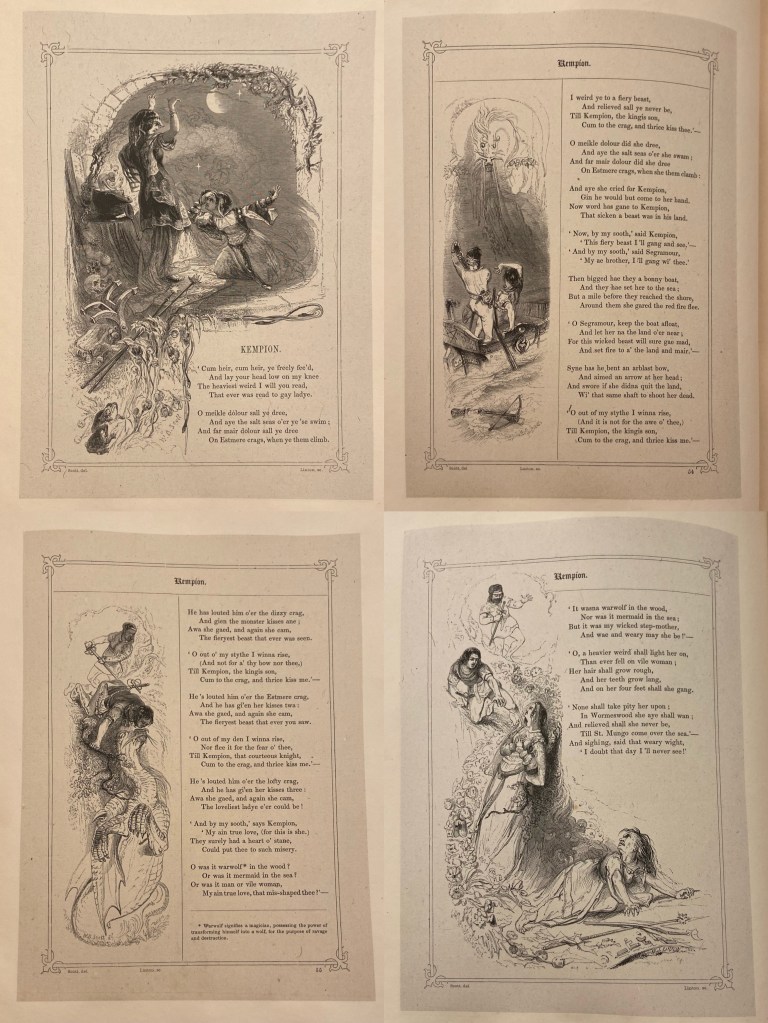

Although The Book of British Ballads is a collection of ballads by different authors, all three poems that impressed Symonds were by Walter Scott, a Scottish historical novelist and poet. In “Kempion,” the heroine is turned into a beast (illustrated as a dragon) by her stepmother, who curses her to remain so until the king’s son, Kempion, comes to kiss her three times. After knowing the beast is in his land, Kempion comes to see her with his brother. The beast lures Kempion to a crag and persuades him to kiss her three times. After the third kiss, she turns back into a lovely woman and accuses her stepmother of cursing her. There are four illustrations to this poem, all of which contains supernatural elements: 1) the wicked stepmother casting a spell on the heroine in order to turn her into a beast; 2) the beast breathing out fire towards Kempion and his companion; 3) Kempion kneeling by the edge of the crag and kissing the beast; 4) the stepmother becoming a beast walking on four feet, staring at Kempion and her stepdaughter.

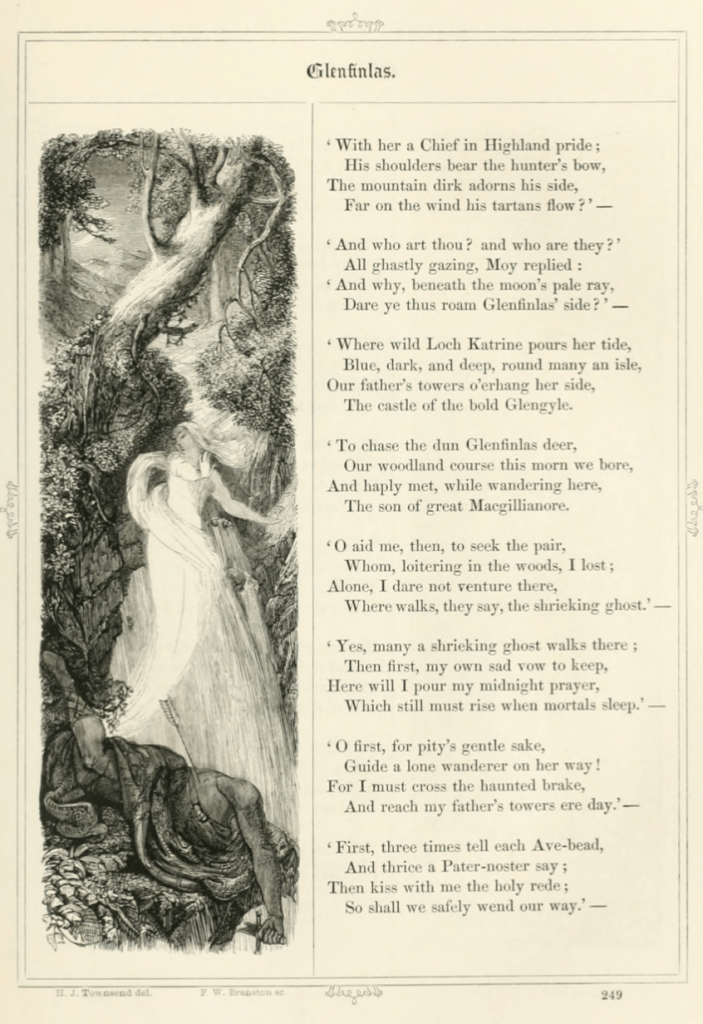

In contrast, the remaining two poems contain real names and appear to be more reality-based. “Glenfinlas” narrates a story happening in Glenfinlas, “a tract of forest-ground, lying in the Highlands of Perthshire, not far from Callender, in Menteith” (The Book of British Ballads, 242). In the ballad, the Highland chieftain Lord Ronald and Moy, another chief from a distant Scottish island, go on a hunting expedition in the wilds of Glenfinlas. Telling Moy that his sweetheart Mary is also hunting with her sister Flora, Ronald leaves Moy in the cabin and goes to a tryst with Mary in a nearby dell, yet never comes back. At midnight, a huntress appears and attempts to lure Moy out, but he refuses. The huntress, revealed as a spirit, flies away, and brings a rain of blood and body fragments upon Ronald. Besides the first illustration depicting a romantic implication of hunting through interactions among a group of god-like figures (they are standing on clouds), there are six pictures with a supernatural element, the huntress spirit. Unlike the ugly beast in “Kempion,” this female figure appears to be a beautiful young woman in all illustrations. However, one picture reminds the reader that her beauty is a disguise for her fatal threat, by placing the corpse of Ronald under her perfect nude body.

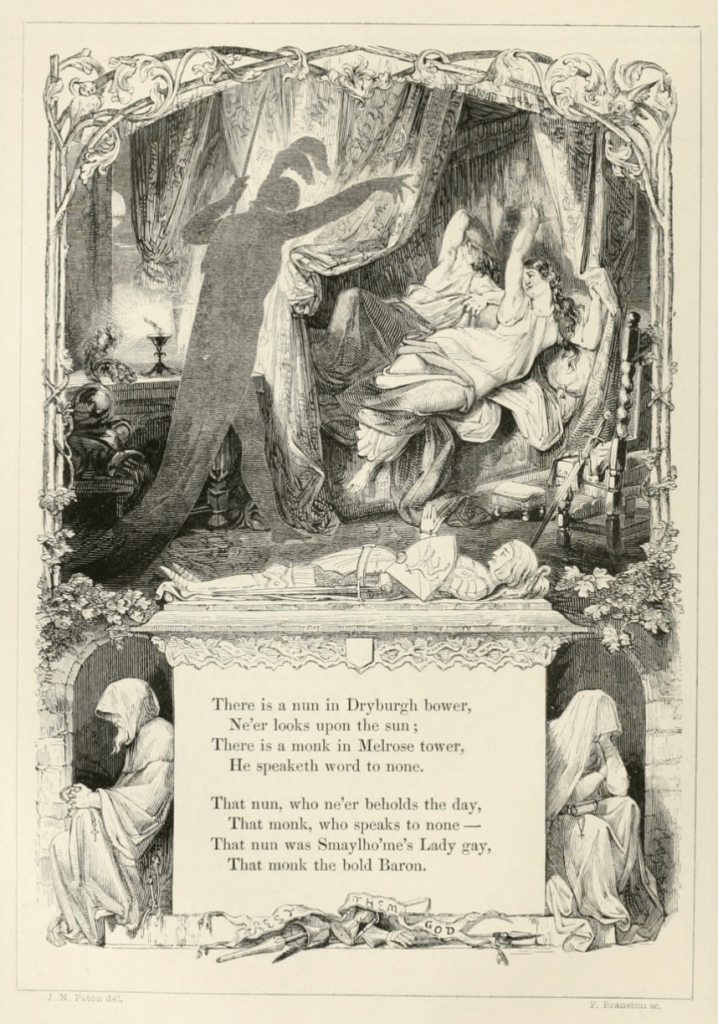

“The Eve of St John” refers to the battle of “Ancram Moor” that took place in 1546. In the poem, the Baron of Smaylho’me has just come back from the battle and learns from his attendants that his lady has fallen in love with a knight and has scheduled a tryst with him on the eve of St. John. However, after knowing the knight’s name, the lord is frightened, because the knight has been killed and buried. At midnight, when the Baron has fallen asleep, the spirit of the knight comes for his lover and tells the truth, leaving his fingermark on her wrist. Since the fact that the knight is a spirit is revealed at last, most illustrations to this poem, except for the last one, appear to be normal. Nevertheless, the last picture, depicting the visit of the knight at midnight, presents a nightmarish scene.

Juxtaposing all three poems and their illustrations, it becomes clear that they convey interchangeability between mankind and supernatural beings. In “Kempion,” the heroine and her stepmother appear as normal humans in the first picture. However, in the next three pictures, they turn into terrifying beasts. In both “Glenfinlas” and “The Eve of St. John,” there is a figure who takes the form of a human being (the huntress in the former and the knight in the latter) but ends up being a spirit. I suspect this interchangeability strengthened by those illustrations could have fostered a sense of distrust towards one’s perception of daily matters, with an intrusive doubt in mind: is what I see real? The boundary between reality and imagination was further blurred by dreams and visions. Symonds writes,

Dreams and visions exercised a far more potent spell. Nigh to them lay madness and utter impotence of self-control.

(Memoirs, 70)

Therefore, the spiritual terrors that Symonds used to experience might have influenced his early personality, which he recognizes as “[b]eing sensitive to the point of suspiciousness” (Memoirs, 68). Meanwhile, Symonds was fully aware that, as opposed to powerful supernatural beings, he was one of the human beings, “things of flesh and blood, brutal and murderous as they might be, [which] could always be taken by the hand and fraternized with” (Memoirs, 69-70). This terrified him.

Also, it is noteworthy that the horrible scenes in “Glenfinlas” and “The Eve of St. John” happen at night. In the Memoirs, Symonds explicitly recalls various things that he used to fear at night: “phantasmal noises, which blended terrifically with the caterwauling of cats upon the roof,” the fancy of “a corpse in a coffin underneath [his] bed,” a recurrent nightmare about a little finger, only visible to him, creeping slowly into the room, etc. (Memoirs, 68). The illustrations might have served as confirmation for Symonds that horrible things tended to happen at night. According to Symonds’s imagination, another spirit dwelling in his childhood home was “the devil [living] near the door-mat in a dark corner of the passage by [his] father’s bedroom” and “[appearing] to [him] there under the shape of a black shadow” (Memoirs, 69). The last illustration of “The Eve of St. John” corresponds to this black shadow, likely triggering Symonds’s fancy of the devil.

Reference:

Hall, Samuel Carter, ed. The Book of British Ballads. London: Jeremiah How, 1842-44.

Symonds, John Addington. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Edited by Amber K. Regis. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.