Imagine dwelling in your father’s library for the whole day, devouring Greek literature. When your eyes need a break, you look out from the windows of Clifton Hill House. The city’s towers, the River Avon, and the sea-going ships are gleaming. Or, you feast your eyes with engravings, photographs, copies of Italian pictures and illustrated books about Greek sculpture. The adolescent Symonds nurtured himself in these ways. Symonds is dreamy and whimsical. He frequently appears to his friends as “languorous” in real-world pursuits as he explains that he “live[s] into emotion through the brooding imagination” (Memoirs, p. 181).

Before Symonds’ imagination could take flight, he needed images that could inspire and suggest. The actual images he took in became elements with which to build sceneries and characters in his fantasy world; no one but himself was able to enter this world of imagination. Nevertheless, it is possible for us to get closer to his fantasy world by looking at images that might have had an impact on him. Doing so, we can begin to visualize his imaginative world using our own imagination. In this blog post, I am going to experiment with this idea by presenting one image from Symonds’ visual library.

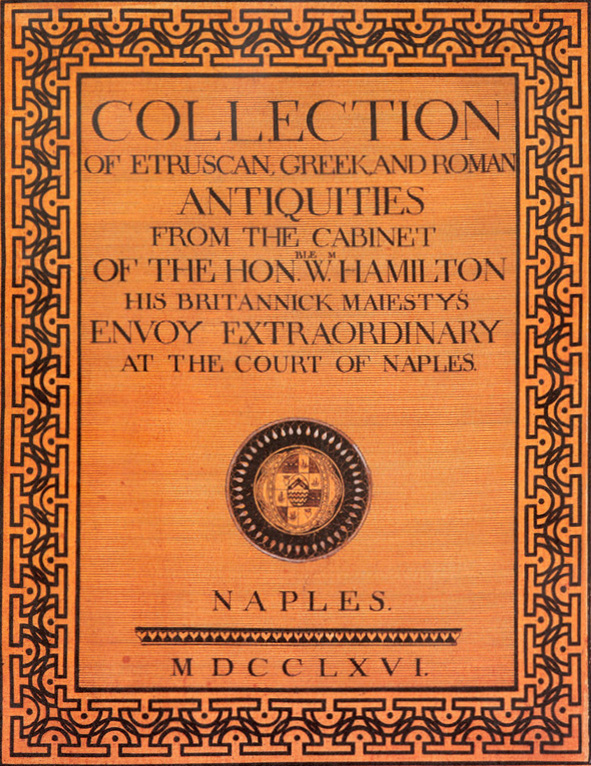

Among Symonds’ favorite picture books was a book of engraved reproductions of the collection of Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803). Hamilton was famous for his large collection of Etruscan, Greek, and Roman antiquities. As the Envoy Extraordinary to Naples for the British empire, Hamilton possessed a charismatic personality that attracted patrons who help with his collecting project, enabling him to amass and study in depth a large number of antiquities. He stood out from his peers, upper-class, rich Englishmen, mainly for his scholastic pursuits in antiquity and, surprisingly, volcanology. With his scientific observations of volcanos, he intended to “convince the world that volcanoes should not be seen as destructive, but on the contrary as extraordinarily productive natural phenomena” (Pierre-Francois, preface). Similar things can be said about Hamilton’s love of antiquity. His motivation went beyond a simple collecting frenzy. As Pierre D’ Hancarville noted in his introduction to the book, Hamilton’s collection merited reproduction because it was “useful to Artists, to Men of Letters and by their means to the World in general” (Pierre-Francois, preface ). So it was not unnatural for Symonds to be drawn to Hamilton’s collections, which would have appealed to him not just because of its contents, but also for its painstaking dedication to a comprehensive understanding of art and culture.

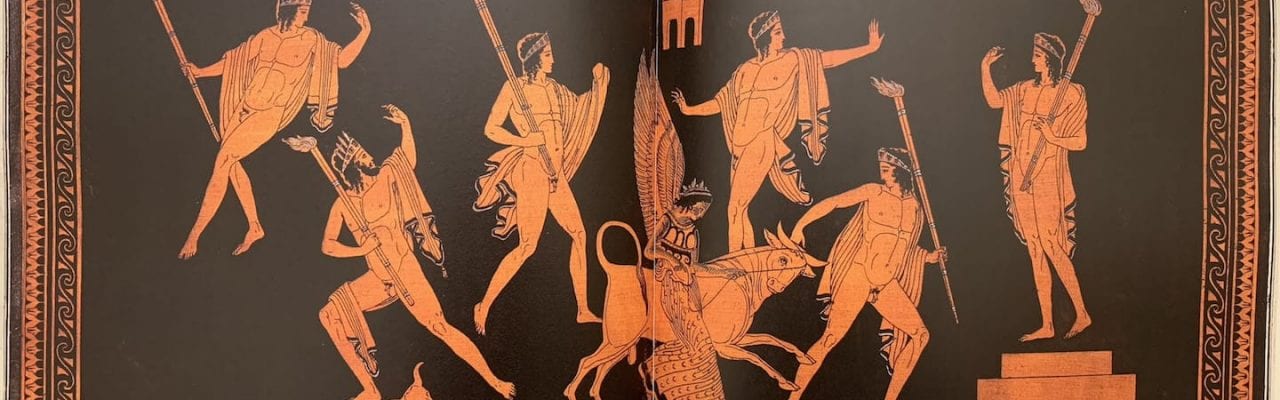

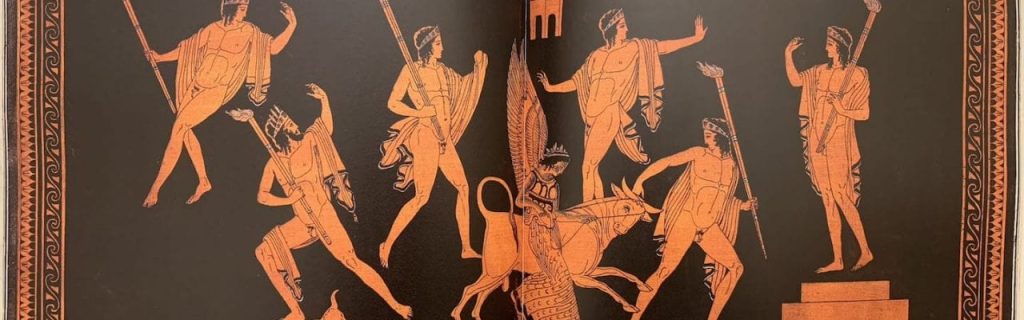

The picture here (on the left) is from an Attic, a region of Greece that contained Athens, bell-krater, labelled III-36 from Collection of Etruscan, Greek and Roman Antiquities from the cabinet of the Hon.W. Hamilton. I chose this image to analyze as the flexible bodily gestures of six half-naked youths here immediately remind me of some similar scenery descriptions I have frequently come across in Symonds’ memoirs. The image is captioned “Surrounded by six youths (five torch-bearers), Nike leads a bull towards a base with two steps.” In Greek mythology, Nike is the goddess of victory. Unlike many other Greek goddesses, Nike is not given many personal histories and characteristics. In other words, she appears more as a symbol than a person. This makes the theme of the image less clear: there are no prominent figures such as Achilles or the brothers Castor and Pollux here that readers could relate to a background story. Paintings like this entail a lesser sense of story-telling, which allows the reader to focus solely on the aesthetics. In other words, since there is not an established setting, it is open to the reader’s interpretation.

Several aspects of this picture stand out to me; the first one is the masculine bodies. The six nude youths in the picture are similar, as they are all well-built with a sheet of muscle between the abdomen and chest. This painting therefore serves as a perfect exemplar for demonstrating Symonds’ own description of his viewing of pictures, aimed at satisfying his desire for “the love of a robust and manly lad, even if it had not been wholly pure.” Such visual experience, he adds, “must have been beneficial to a boy like me [him]” (Memoirs, p.118). Another notable feature of this painting is that it depicts six masculine youths, rather than one or a couple. More than anything, the painting strikes me first as a reminder of Symonds’ account of how he “used to fancy” himself “crouched upon the floor amid a company of naked adult men: sailors.” It is worth noting that the awakening of Symonds’ erotic imagination here entails scenes of a group of masculine youths (sailors) rather than a single one. The painting at hand would satisfy exactly this secret desire.

Nike, the only female here, is placed in the center of the painting. Nike’s covered body, tender gesture, and her state of being protected by the brawny youths around her might very well have tempted Symonds to fantasize in the same way that he did about Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis, about which he reflected, “those adult males, the shaggy and brawny sailors, without entirely disappearing, began to be superseded in my fancy by an adolescent Adonis…She [Venus] only expressed my own relation to the desirable male.” (Memoirs, p.101). In this case, Nike would be in the position of “Venus” for him, a symbol that only intensifies his yearning for the nearby youths.

Nevertheless, I would argue that the picture is more than a graphic representation of Symonds’ erotic ideal. The torches in the hands of the youths around Nike indicate that it is night time. Oddly enough, in the painting, Nike doesn’t hold a torch herself, which suggests that she is not just guarded, but is also guided by the six young men; they are leading the way for her to travel in the darkness. In return, Nike brings victory to the youths. Such a relationship itself resembles the comradeship that Symonds often mentions, which surpassed the realm of sexual imagination. The relationship of guarding, guiding, and eventually needing one another is akin to what Symonds craved in a romantic relationship, independent of bodily desire. As Symonds rested his eyes on the painting, both his romantic and erotic imaginations would have been inspired; these two elements worked in tandem to enhance his sensual pleasure.

Works Cited:

- Regis, Amber K. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK , 2016.

- Pierre-Francois Hugues D’Hancarville, The Collection of Antiquities from the Cabinet of Sir William Hamilton. Cologne: TASCHEN, 2004.