Clifton Hill House loomed large over the life of John Addington Symonds. This structure, with its bright neoclassical facade and its dark Victorian interior could stand in for Symonds himself. The scholar’s luminous career also hid a brooding and tortured inner life. Clifton Hill House’s paneled living rooms full of curiosities formed the backdrop for the development of Symonds’ unique aesthetic sense, as well as his first introduction to the beauty of the male body in the art books of his family’s library. It is no surprise then that, when he sold the house his father had bought years ago, he let go of rather more than he bargained for.

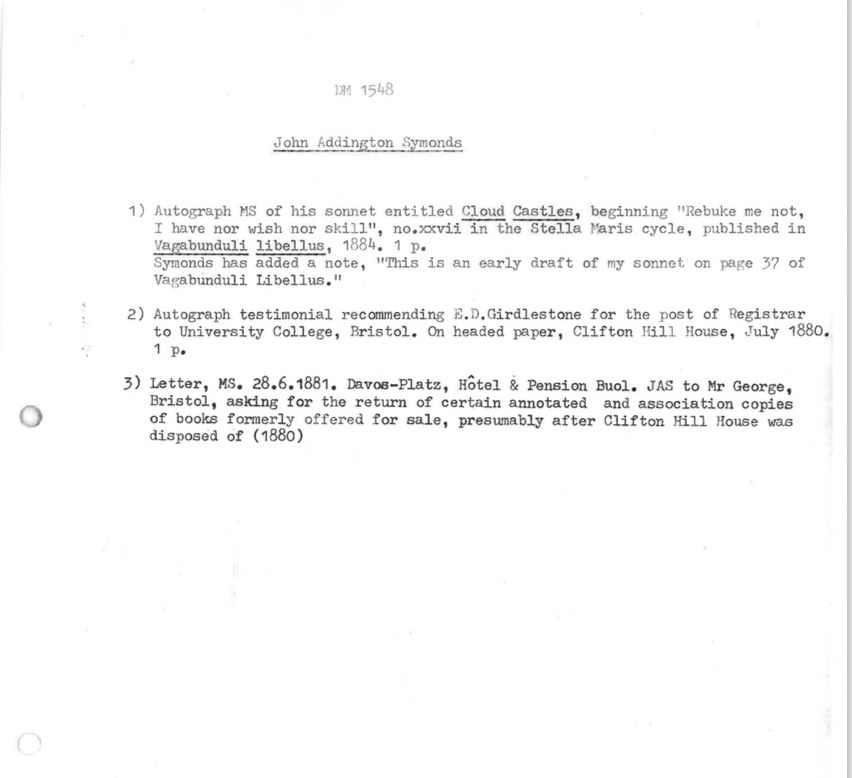

So begins our archival mystery. In the finding aide to the John Addington Symonds Archive at Bristol University, a chimeric document made piecemeal from handwritten inventories, typescript accounts, and small computer files describing donations of Symonds’ ephemera to the college after his death, we find a curious item on page 122:

3) Letter, MS.28.6.1881. Davos-Platz, Hotel & Pension Buol. JAS to Mr George, Bristol, asking for the return of certain annotated and association copies of books formerly offered for sale, presumably after Clifton Hill House was disposed of (1880)

Bristol University Finding Aid

Unraveling the complex poetics of this archive gives us a series of clues:

1. This piece of paper is the third item in a larger box containing documents related to Symonds.

2. It was handwritten on the twenty-eighth of June, 1881.

3. It was not written in England, but rather across the sea in Switzerland.

4. The letter is addressed Mr. George, a bookseller in Bristol, asking for the return of some books that were mistakenly sent out for sale. The modern archivist at University of Bristol conjectures based on the date of the letter that they were part of Symonds’ library at Clifton Hill house, and were given to the bookseller as the rest of the Symonds property was being “disposed of.”

This disposal held great significance for Symonds, as he recounts in a letter to Henry Sidgwick on July 8, 1880:

‘I have parted with my past by destroying nearly the whole of my correspondence…It was rather pretty to see Catherine and my four children all engaged in tearing up the letters of a lifetime! We sat on the floor and the old leaves grew above us mountains high. By the same fell stroke I destroyed the correspondence of my forefathers from the 17th century–from an old Independent Minister who had known Bunyan–downwards…I feel rather like a criminal to have burned the tares and the wheat together of this harvest. I was driven to do so by having to break up this our home, and to go forth homeless. Old letters must have been put into a box to be rummaged and destroyed by my executors. I preferred a solemn concremation in my garden underneath the trees, attended with the conclamatio [shouting] of my spirit as I said to the flaming pages “Avete atque valete.” [“Goodbye and farewell.” ref. Catullus, Carmina 101] So you see we are about to leave Clifton Hill house: “To be let or sold”!’ (Letters 1186)

Symonds, Letters 2:639-641, to Henry Sidgwick (Clifton July 8 [1880]).

When he lit the match in the garden that day, Symonds freed himself from his own past. However, he says goodbye with pointed reference to another, more remote past, that of the ancient Roman poet Catullus. The phrase “avete atque valete” directly recalls the final line Catullus Carmina 101 (linked above), which portrays the poet returning to Rome for the funeral of his brother and weeping over the “mute ash” of the funeral pyre. With Catullus in mind, Symonds’ bonfire is more than a documentary concern to him. This reference shows that the Victorian viewed the pieces of paper that made up his heritage as a body to be consumed by the flames, as a collection of voices to be made silent. Disposing of the remains of Clifton Hill house, then, was for Symonds a funeral rite, an act of mourning that perhaps would allow him to move into a new chapter of his life.

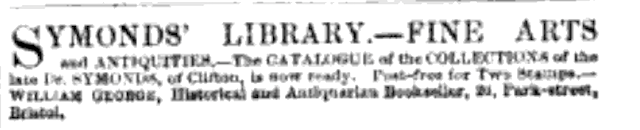

5. In the letters throughout the following months, Symonds discusses auctioning off his father’s valuable collection of books and art objects. Although he doesn’t mention George by name, this advertisement in The Academy is presumably for the sale of at least a piece of the Symonds estate from Clifton Hill house. It identifies our Mr. George as William George, founder of William George and Sons bookshop in 1847. This shop, having been bought by the chain store Blackwells in the 1920s, still sold books on Park street in Bristol until 2012, when the Blackwells location was bought by Jamie Oliver’s fast casual restaurant “Jamie’s Italian.” (Image of the shop’s new look available here. For an entertaining review of “Jamie’s Italian” click here.) What will become of the building after the ignominious demise of Oliver’s foray into the restaurant business remains to be seen.

This leaves one pressing question: What was Symonds’ letter to William George really about? If Symonds was trying to make a new start, why did he need these books back so badly?

6. A perusal of the year 1881 in The Letters of John Addington Symonds, edited by Schneller and Peters, reveals that this letter to Mr. George is conspicuously absent. However, he is mentioned by Symonds one other time, and what he says about him and the missing books provides at least a partial solution to our question above:

I have been receiving letters from Mrs Wilson (School House) about a book wh once belonged to me & is full of Ms notes–how many of such indiscretions had got into circulation I am afraid to think. The Wilsons bought it of George the bookseller [in Bristol].

Symonds, Letters 3:365 (1709), to Henry Graham Dakyns (Am Hof, Davos Platz, Switzerland: March 27, 1889).

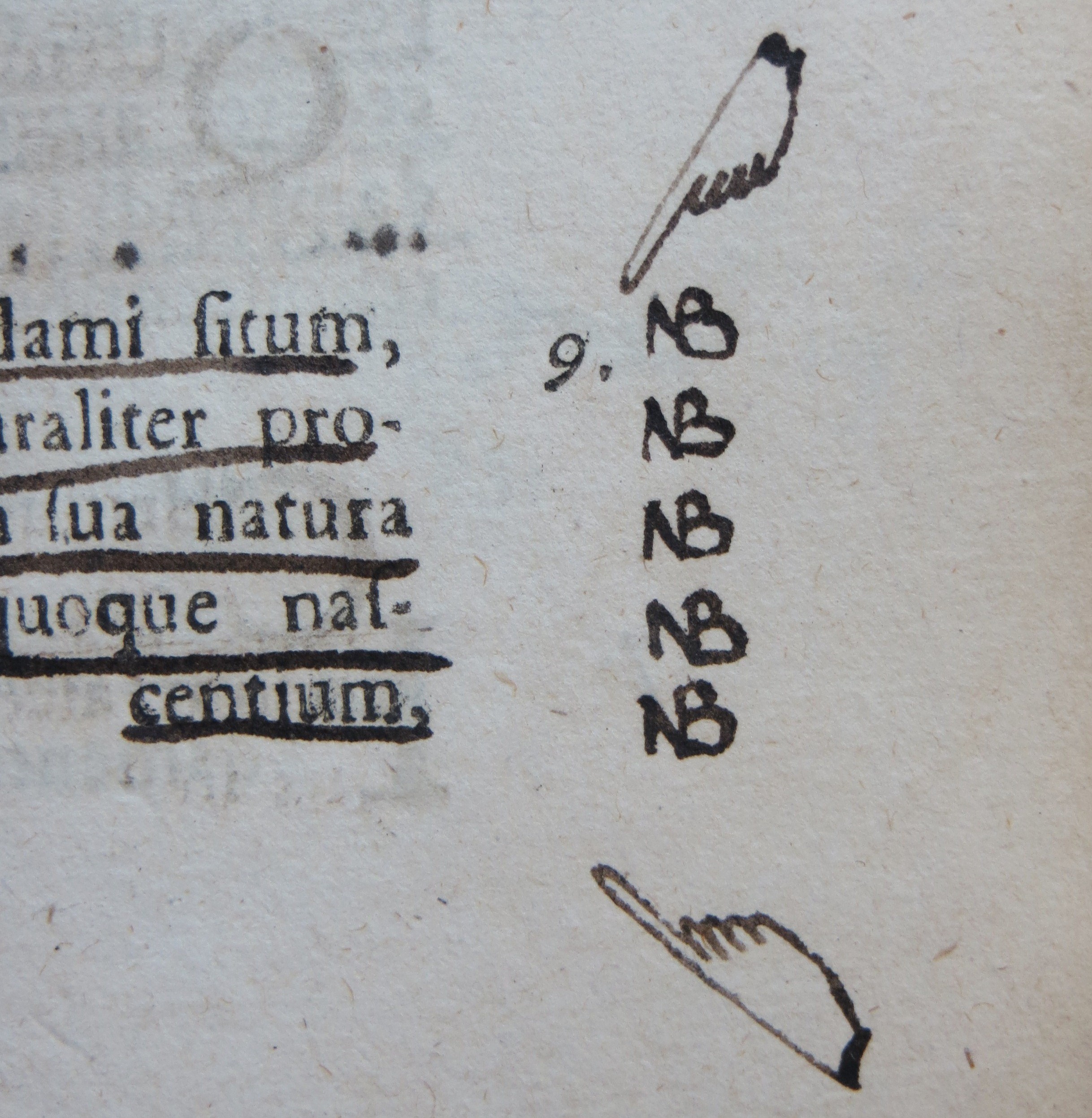

From this we can conjecture that it wasn’t the loss of the books themselves that had upset Symonds, but the exposure of the handwritten notes left in the margins. To someone that reads with pen in hand, the things written in a book are an extension of the mind. We can only imagine the horror that gripped Symonds, who thought he had made a definitive break with his English past, at the thought of his private thoughts spreading through the bookshops of England like a slick of oil on a London puddle. What would he feel now, given that our task, as not only detectives but historians, is to track down those very thoughts and lay them bare?

So where did the books go? Is the solution in the estate of Mrs. Wilson, wife of the head of Clifton College at the time, or perhaps in some catalogue kept by Mr. George and lying in wait for us in a digital repository somewhere? The truth remains to be seen, and the Symonds lab is on the case!