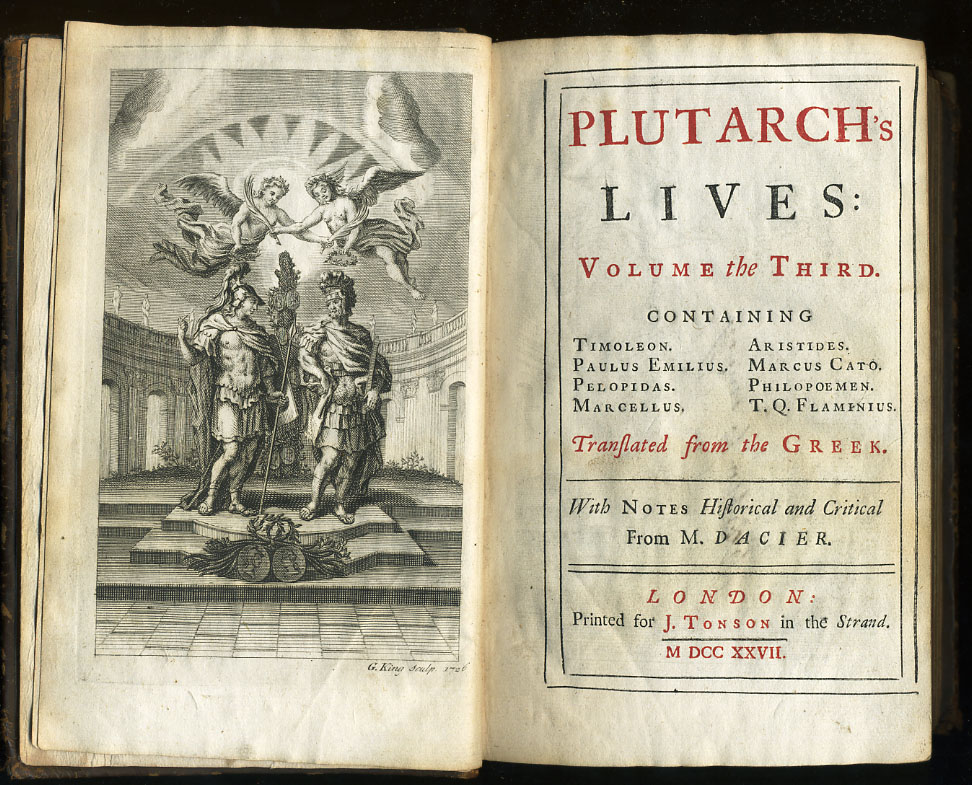

Two ways to look deeply into an ancient culture are to read about the lives of its people and the social ideologies they formed. Plutarch produced one work for each. As an essayist, Plutarch has a collection of articles, Moralia, including essays and transcribed speeches, shedding light on the Greek and Roman livings in general. As a biographer, Plutarch is known for Lives/Parallel Lives, which chronicles a series of famous Greek and Roman people (Mark Antony for example) in a detailed manner. Like Karl Marx to a sociology class, Plutarch is one of those names you are unlikely to miss on your Classics 101 (says me who is not a classics major, yet) reading list as his works provide a basic understanding into the social, philosophical, and spiritual frameworks of ancient Greek culture.

It is curious to see how our protagonist John Addington Symonds, who is a classics scholar and to whom Greek life is “of intense personal interest,” came across Plutarch. Several times in his memoirs and letters, he mentioned reading Plutarch as part of his personal life. On his trip to Italy, JAS brought Plutarch with him to read all day long in a cabin and in Sicily. He expressed his feeling of being in Italy as to “get so many of the good things of the world,” Plutarch being one of them. In another letter, he mentions that his 10-year-old Janet read Plutarch’s Lives with him every day after breakfast.

What, then, did JAS find so invaluable in Plutarch’s works? As aforementioned, Plutarch’s works are more like an encyclopedia of Greek livings and society. It is therefore crucial and intriguing for us to see what is it that draws the most attention from JAS among the plethora of ancient Greek characters and ideologies Plutarch has to offer. We might also want to ask what the connection is there between those characters and JAS’s personal life and beliefs.

Plutarch’s Lives as a source that demonstrates the military origin of Greek love. The Life of Pelopidas brings up the Sacred Band, an army led by Pelopidas, and is “cemented by friendship grounded upon love” between soldiers. The Sacred Band, is said to be invincible as lovers would never want to appear base in sight of the beloved, as supported in Plutarch’s The Dialogue on Love: “For love makes a man clever …the coward brave, just as men make soft wood tough by hardening it in the fire.” Symonds also touches lightly on other similar stories to support this claim. Such love that bred in a military setting rests on what Symonds calls comradeship, the “companion in battle…in public and private affairs of life,”The relationship between Pelopidas and Epaminondas in the Life of Pelopidas fits this description. Both being free of a vanity towards “personal wealth and glory,” they are bonded by a “divine desire of seeing their country glorious by their exertions.” The affection between them further ferments through participating in public actions and fighting together at battles. Evidence from Symonds’ memoirs and letters suggest that such friendship infiltrates its influence from his scholastic to personal life, exciting his romantic imagination. Symonds describes his affection for Willie Dyer, his first love, as “a passionate yet pure love between friend and friend…the vision of a comrade, seemed at the time to be made actual in him [Willie]”. As a boy, Symonds wrote an unpublished poem, “Epaminondas,” which is mentioned in his letters. Although we as readers cannot see the actual poem, it is hard not to draw a connection between Epaminondas and Symonds himself, both of whom are voracious in philosophizing and engaged in boy love. Moreover, in his memoir, Symonds confesses his attraction towards masculinity which indicates a possibility of him projecting himself on Epaminondas; he has an unusual friendship with Pelopidas, who is keen on bodily actions. It is funny to read that Pelopidas and Epaminondas once worked together as colleagues “in supreme command and gained the greater part of the nations there, including all Arcadia.”, comparing this to the fact that Symonds famously euphemizes his ideal Greek love as the “Arcadian Love,” distinguishing it from Greek love which includes also a baser form of paiderastia.

Symonds’ referral to Plutarch is centered on the debate about love and the characters that exemplify a pure, passionate relationship seen in the Greek military, which drives his intellectual inquiry and unworldly personal imagination. However, upon reading Plutarch, I also recognize traces of other morals from Plutarch that might have been correlated to Symonds’ life. As stated by Arthur Hugh Clough, “Plutarch is a moralist, not a historian.” Plutarch’s own moral values are made apparent in his Lives, partly reflecting the ideals the Greek society had aspired to. Besides the Life of Pelopidas, Symonds mentions the Life of Solon quite frequently as well. According to Plutarch, Pelopidas, Epaminondas, and Solon share one commonality: they are “no admirers of riches.” Symonds, at a very young age, had also discovered that he “felt no desire for wealth, no mere wish to cut a figure in society,” In this light, it is Symonds’ whole nature, or at least some nature more than mere sexual orientation, that resonates with the essential virtues of the Greek heroes as portrayed by Plutarch. Thus, this observation suggests to me that his indulgence into the ancient Greek history and literature would not be a choice, but a destiny.

Featured image: Detail from cover of Plutarch’s Lives, trans. John Dryden, rev. Arthur Hugh Clough. Modern Library: 1977.

Works Cited:

Sean Brady and John Addington Symonds, “A Problem in Greek Ethics,” essay, in John Addington Symonds (1840-1893) and Homosexuality: a Critical Edition of Sources (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 21.

Regis, Amber K. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK , 2016.

Symonds, John Addington, and Horatio F Brown. Letters and Papers of John Addington Symonds. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1923.

Symonds, John Addington. A Problem In Modern Ethics: Being an Inquiry Into the Phenomenon of Sexual Inversion. London, 1896.

Plutarch. “Plutarch’s lives” London, Dent; New York, Dutton [1969-71; vol. 1&2, 1970] Dryden ed., rev. with an introd. by Arthur Hugh Clough.