In his Memoirs, John Addington Symonds writes of his relationship with his Classics Professor John Conington at Harrow as an “almost wholly good” friendship (170). He describes Conington as a “scrupulously moral and cautious man,” yet also as someone that “sympathized with romantic attachments for boys” (170). Based on Symonds’ account, their relationship was not erotically charged, yet we can infer that Conington likely saw elements of himself reflected in Symonds’ interest in his male peers. This is further supported by the fact that Conington gave Symonds a copy of Ionica by William Johnson, later known as William Johnson Cory.

According to a note from a reprinting of the 1891 volume, the 1858 edition of Ionica that Symonds possessed contained forty-eight poems, which were formally published by Smith, Elder, and Company. One of the preeminent publishers of the era, Smith, Elder, and Company were most well-known for publishing Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (albeit under a pseudonym). Thus, it isn’t entirely shocking that they were willing to risk printing Ionica despite its references to love between men. As for Johnson himself, we might imagine that his highly respected status as the head of Eton afforded him the benefit of the doubt to a greater degree than most.

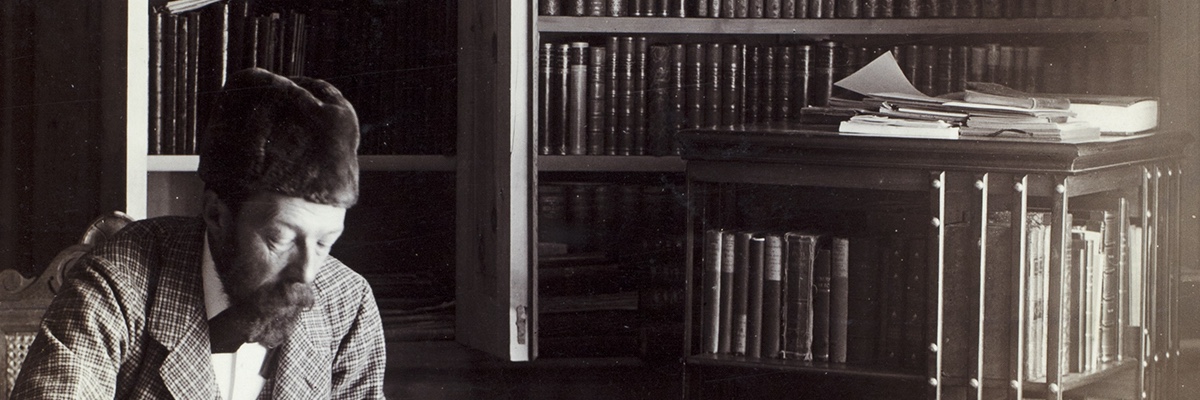

Still, it appears that by 1877 even Johnson felt the need to exercise greater caution. He privately printed a second, anonymous volume of twenty-five poems under the title of “Ionica II.” This second collection did not even include a title page. Interestingly, it also did not contain punctuation, extending a kind of non-conformity to its structure. Evidently, as is supported by Symonds’ Memoirs and the need for multiple reprintings, Ionica and Ionica II captivated an engaged readership. Given this, in 1891, a volume combining both sets of poems – eighty-five in total – was formally published. Hopkins possesses a copy of this edition in its Special Collections.

Symonds writes in his Memoirs that it was through reading Ionica that he first learned of Johnson’s “affair” with Charlie Wood, one of his “pupils” (170). This “love story” struck Symonds, “straight to my heart” and “inflamed my imagination” (170). Lines such as “For him who led me through that park; / And though a stranger throw aside / Such grains of common sentiment, / Yet let your haughty head be bent” from the poem “Desiderato” resonated with Symonds (Cory). However, their influence was not benign. In his own words, Symonds writes that they “helped to form a dream world of unhealthy fancies about love” (170).

He was so moved by Ionica, that Symonds wrote to William Johnson Cory seeking advice on “the state of my own feelings,” his love for his male peers (170). According to Symonds, Johnson replied with a letter on the practice of Greek “paiderastia in modern times” (170). This correspondence seems likely to have influenced Symonds’ essay on the topic of male love in Ancient Greece, “A Problem in Greek Ethics,” which, although it was initially printed only privately, found a similarly enthusiastic audience as Ionica.

Ionica not only left an indelible impact on Symonds and his mode of thinking about sexuality, it also played a role in facilitating a conversation between Symonds and Conington that would alter several of their peers’ lives. It was during a discussion of “passion between male persons” spurred by Ionica that Symonds revealed to his professor that his former headmaster, C.J. Vaughan, and his classmate at Harrow, Alfred Pretor, had engaged in an affair (171). While his friends, including Pretor himself, felt betrayed and ended their relationships with Symonds, Symonds viewed revealing what he knew as his moral obligation. The subsequent chain of events led to Vaughan stepping down from his position at Harrow and declining two bishoprics (174). It is ironic that, rather than existing as a bridge between Symonds’s concept closer to an empathetic understanding of his peers’ affairs, Ionica figured prominently in his memory as associated with the ruin of several of his closest friendships.

Works Cited:

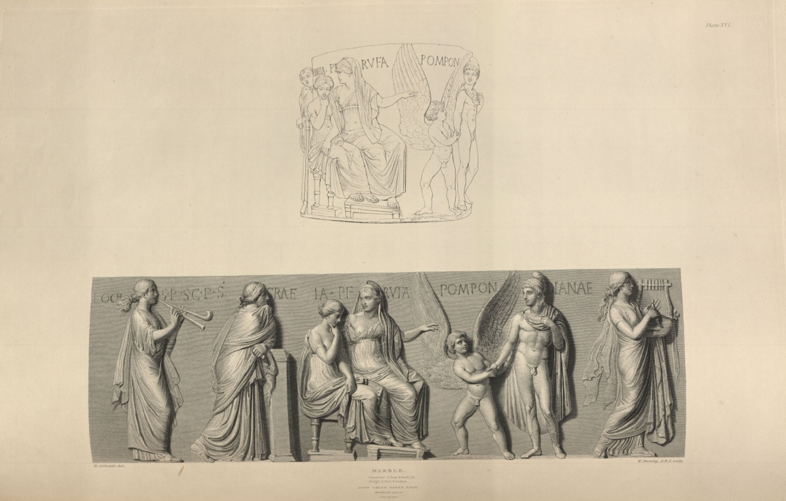

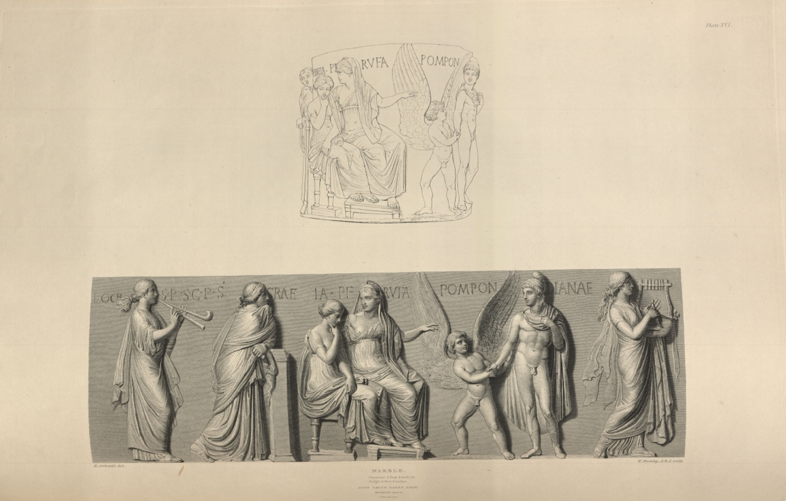

Cory, William Johnson. Ionica. London: G. Allen, 1891.

Symonds, John Addington. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Edited by Amber K. Regis. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.