In 1909, 16 years after Symonds’ death, a prominent bookseller in Bristol published a catalogue of Symonds’ home library, shedding light on his literary preferences and direct influences. Our ability to partially reconstruct his lost library through the catalogue gives us the chance to understand Symonds not just as an author, but also as a philosopher, historian, traveler, and avid reader. Among the books of poetry, art, sexology, and classical antiquity that once were on his bookshelves, a seemingly fun adventure novel by a name I knew caught my attention.

In 1846, Herman Melville published his travel book Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life During a Four Months’ Residence in a Valley of the Marquesas. Not many years later, Symonds owned and likely read a copy of this book, and we can only postulate on why.

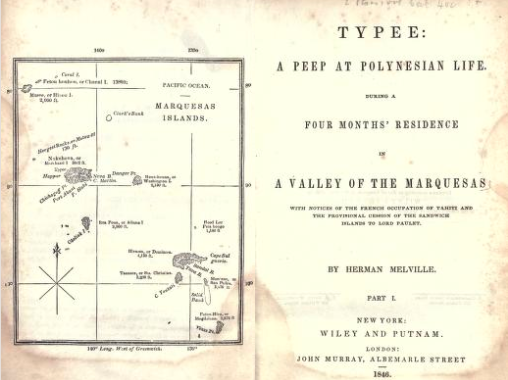

Frontispiece and title page of Herman Mevile, Typee… (New York: Wiley and Putnam, and London: John Murray, 1846). From the University of California Libraries via the Internet Archive

Typee, Melville’s first book, is a highly romanticized and fictionalized account of his one-month stay in the Marquesas. Melville drew from his experiences, from his imagination, and from accounts by Pacific explorers, departing from the truth of what actually happened to make a more entertaining story. Typee is a story of escape, capture, and re-escape, alluding to themes of cannibalism, colonialism, natural beauty, and the perceived simplicity of “native” lifestyle.

While Symonds never visited the Pacific islands, he was an avid traveler and travel writer – and in these writings can occasionally be discerned a sympathy for Melville’s South Seas experience. During a trip to Normandy, for instance, Symonds kept a diary, a “misty guide book,” in which he describes his own seaside isolation:

“Like a formless Monaco, but with so much more of suggestion in the northern sea. The Channel Islands are visible from the terrace of the town, and long stretches of arid dunes stretching away northwards, salt, barren, uninviting.”

(Memoirs, 298)

The emotions that the coast evoke in him is fodder for Symonds’ own poetry. In the summer of 1867 in London, he writes the Song of Cyclades, describing the burden of loneliness that he shares with the islands.

“The burden of Cyclades, the burden of many islands, of islands on the sea of my own life. (There is firm ground beneath; I am not all islands and sea.)

The hours of weeping because I was not strong, and no companions sought me; nor beautiful, and women did not love me; nor great, and no poems were in me.

The hour of passionate weeping for the sin and shame upon me—the hour of wailing for the unkindness of friends—the hour of hot blushing for the thoughts of my own soul: solitary, self-centred, judgment and confession hours. “

Memoirs, 318

The first edition of Typee was published in New York (Wiley and Putnam) and London (John Murray) in 1846 as part of a collection of travel books. It was Melville’s first published book after a stint of articles and short stories. After the publication of Typee, Melville became a more successful and well-known writer, with the help of his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, eventually publishing his whaling novel Moby-Dick in 1851.

The first edition was published as part of “Murray’s Colonial and Home Library,” a collection for readers in the British colonies to compete with piracies, often by American publishers. We know from the 1909 William George’s Sons catalogue that the edition Symonds owned was published in 1861, the year in which John Murray published it in London. The small octavo edition sold for two shillings and six pence. The 1861 edition is in all likelihood a reprint of the first edition, published cooperatively with an American publisher

Did Symonds read Melville’s Moby-Dick? The author is not mentioned at all in his Memoirs or his Letters, so we cannot know for sure. But Melville was a contemporary of Symonds’ time, and Symonds was familiar with the works of other American writers such as Walt Whitman. If Symonds read Typee, it is possible he also read the better-known Moby-Dick, first published in 1851. Symonds could have become better acquainted with Herman Melville’s works after the publication of Moby-Dick and gone to read more of his lesser-known works, buying a later 1861 edition of his earlier book, Typee. Perhaps these naturalistic adventure novels were what he read as part of his research in travel writing.

Perhaps Symonds never even read Moby-Dick, but specifically sought out Typee for its interesting take on travel literature, by combining fiction and fact. Symonds himself wrote many travel books that combined his own experiences with a scholarly assessment of the land, society, and culture, including his book Sketches and Studies in Southern Europe (1880) and his book Our Life in the Swiss Highlands (1892) written cooperatively with his daughter Margaret.

Symonds himself loved to travel; here we see what Symonds may have read for when he wished to travel in his mind– a wild adventure story with tales of far-away travel that combines whimsy with the eloquent skill of an established author, undoubtedly influential in Symonds’ own later works. Exploring the lost library of Symonds allows us to appreciate him as a person and better understand his life outside of academia.

For reference:

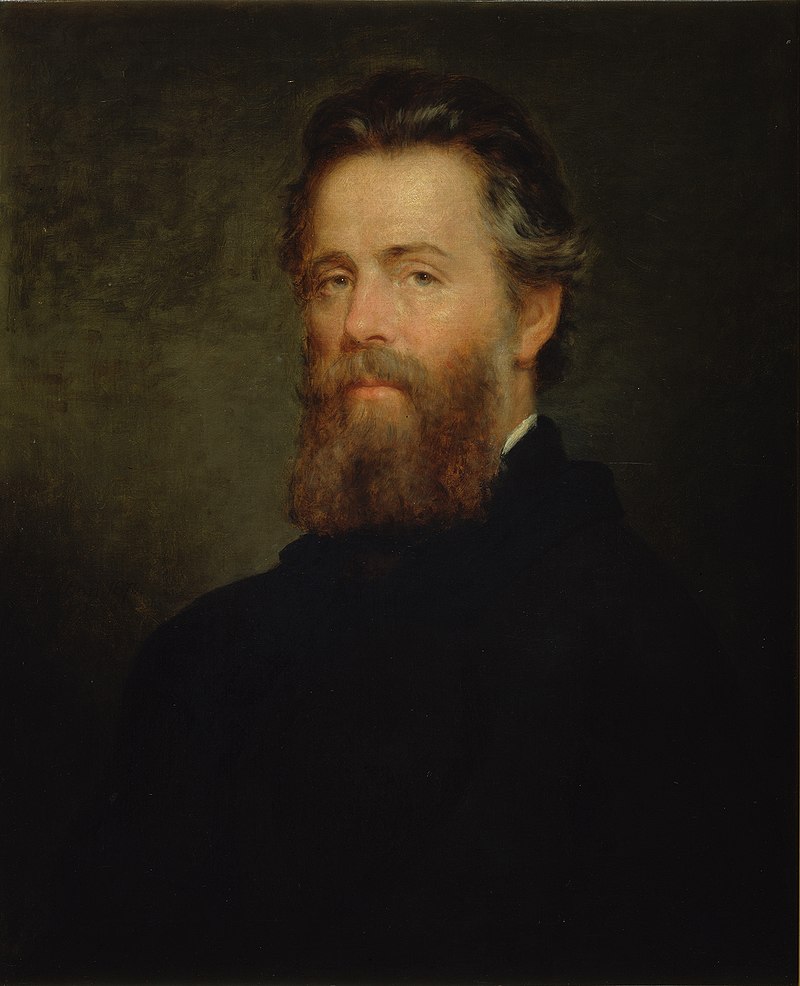

“Herman Melville.” 1870. Oil painting by Joseph Oriel, commissioned and presented to the family by Melville’s brother-in-law, John Hoadley. Houghton Library, Harvard University. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons.

Herman Melville (August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period best known for Typee (1846), a romantic account of his experiences in Polynesian life, and his whaling novel Moby-Dick (1851). His work was almost forgotten during his last thirty years. His writing draws on his experience at sea as a common sailor, exploration of literature and philosophy, and engagement in the contradictions of American society in a period of rapid change.

Works Cited:

Featured image is “Mekong pirogue at sunset in the 4000 islands.” Wikimedia Commons: Featured Pictures.

Melville, Herman. Typee, or Four Months’ Residence in the Marquesas. London: John Murray, 1861.

The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Amber K. Regis, editor. London: Palgrave Macmillan Publishing, 2016, pp 1-587. Print.