When he began to read in his youth, John Addington Symonds was mentally precocious and aware of the amorous subtleties of Greek literature; he was particularly attracted to certain male figures, like the Adonis of Shakespeare’s poems, Hermes in Homer, and the Praxitelean Cupid (Memoirs 118). In adolescence, he enjoyed sleeping visions of beautiful young men and exquisite Greek statues, finding a poetic pleasure in ideal forms.

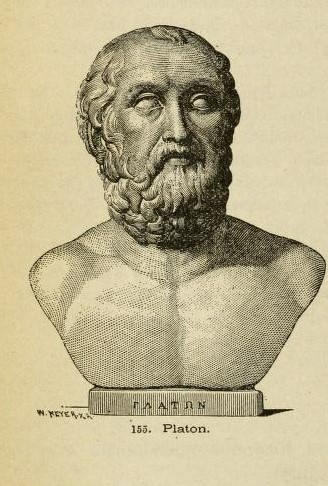

In his eighteenth year, a decisive event in his sexuality occurred: he read Plato.

Symonds’ first introduction to Plato was during summer vacation, when he joined a reading party with his friends John Conington and Thomas Green, in a farmhouse on Lake Coniston. There in July 1860, Symonds writes to Reverend Stephens, the Dean of Winchester, “Green is coaching me in Plato. He does it well, for he knows an immense deal about the Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy. On the other hand, because he is a very original thinker, he does not express himself quite clearly and fluently as such beginners as myself would like” (Letters 1.251 (149)).

Reading Plato, especially the Phaedrus and the Symposium, was a revelation for Symonds in terms of the notion of Greek ideal love; it was the catalyst for his own self-reflection on homosexuality:

“Here in the Phaedrus and the Symposium, I discovered the true Liber Amoris [Book of Love] at last, the revelation I had been waiting for, the consecration of a long-cherished idealism. It was just as though the voice of my own soul spoke to me through Plato, as though in some antenatal experience I had lived the life of a philosophical Greek lover” (Memoirs 152).

He was introduced to a new world and he felt his own nature was revealed to him. He fell for a boy, a choir boy named Willie Dyer, and the only two kisses they ever shared “were the most perfect joys he ever felt.” Symonds cites the morning he first met him, the 10th of April 1868, as “the birth of [his] real self” (Memoirs 157).

Seeing the crude sensuality of the boys at Harrow School, he believed that he was saved by finding the aesthetic Platonic idealism of erotic instinct. The study of Plato allowed Symonds the possibility of reconciling his “inborn instincts of masculine love” with his “higher aspiration after noble passion” (Memoirs 152). Plato did not think of carnal human love but of the ideal love of beauty, truth, goodness, and perfection. It is the revelation of this love that drives Symonds’ studies; he devours Greek literature and art as “love unsealed the eyes of [his] soul” (Memoirs 159).

Later at Oxford, he fell violently in love with a chorister called Alfred Brooke, with a passion both more sensual and more ideal than he had ever felt before (Memoirs 159). In describing the “genius” of Greek love, he writes a poem of his own heart’s experience, being thoroughly disarmed by the charm of this man, and holding his love as a secret from his family and friends:

Upon my bed I turn in the night-watches:

I clench my fist, and beat my brow; the flesh

Throbs in revolt, and my faint soul is faltering.

I thirst for him as thirsts the hunted hart

For water-brooks: I weep and wail for him,

For him from whom I turned aside, for him

On whom I trampled. Yea, I loathe my longing.Before my study-window once he passed:

(Memoirs 199)

The Phaedrus fell from my unheeding hands.

He smiled and beckoned, with frank open face

Wafting fair messages of fruitful joy.

I would not answer, hardly looked at him,

Holding my breath and at the curtain clutching

Till he was gone. Then down into the road

Rushed, followed him, restrained my racing feet,

Fell on the garden grass and leaves, and wrestled.

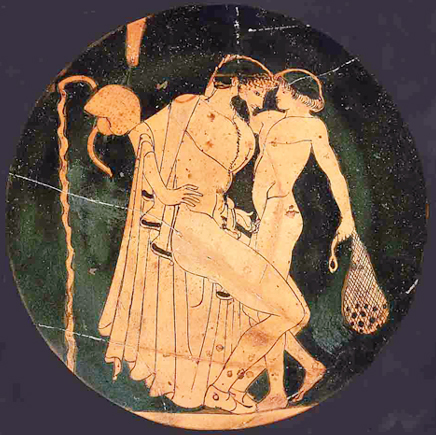

To Symonds, the sensual appetites were, theoretically at least, excluded from Platonic idea love. It was, as Plato says, the divine in human flesh: “the lightening vision / the radiant sight of the lover” (Greek Ethics xv)

By 1865, Symonds was well-read in Plato and was aware of the controversy that surrounded the topic of the Greek ideal love between a man and an adolescent – paederastia (παιδεραστία). Yet this social opprobrium did not hinder him from pursuing this love in his studies. If anything, it encouraged him to share and discuss it with his friends. Symonds sends Wright’s translation of Plato’s Phaedrus and Protagoras (1848) to Clementina Strong as recommended reading, with a caveat that “you will find some things that jar upon our modern taste but nothing that ought to shock the most refined sensibilities” (Letters 1.575 (434). While he was aware of the “sexual perversion,” he still wished to pursue it on a scholarly and personal level.

In his scholarly field, Symonds had a few disagreements with his Classics professor Benjamin Jowett, who intended to publish an essay on Greek male love as part of his translated edition of Plato’s Dialogues but decided to abandon the idea. Symonds was surprised that Jowett saw Plato’s treatment of Greek male love as “mainly a figure of speech” and wrote a letter to him in 1889, insisting that it is actually an “innate passion” and “injurious to a certain number of predisposed young men.” (Letters 3.345 (1894)).

Here Symonds expressed his idea of Platonic Greek male love as a revelation to many people, later including himself. He believed that Greek history and literature confirmed the admitted possibility, and that ideal male love was still a “present poignant reality” to some whom find it personally interesting, reading Plato as their version of the Bible.

Symonds began to understand Greek masculine love as more a condition of the mind and heart, rather than a psychological disease. While working with Havelock Ellis on their publication of Sexual Inversion, Symonds sent him a letter discussing the chapter on the Greek history of sexuality: “One great difficulty I forsee: It is that I do not think it will be possible to conceal the fact that sexual anomaly (as in Greece) is often a matter of preference rather than of fixed physiological or morbid diathesis” (Letters 3.787 (2062)).

Greek love was in its origin and essence militaristic; fire and valor rather than tenderness or tears were the external expression of this passion and effeminacy had no place in it. In his A Problem in Greek Ethics, Symonds references a speech from Plato’s Symposium 12: Phaedrus says, “For what lover would not choose rather to be seen by all mankind than by his beloved, either when abandoning his post or throwing away his arms? He would be ready to die a thousand deaths rather than endure this. Or who would desert his beloved or fail him in the hour of danger? The veriest coward would become an inspired hero, equal to the bravest, at such a time; love would inspire him; that courage which, as Homer says, the god breathes into the soul of heroes, love of his own nature inspires into the lover.” (Greek Ethics vii).

The citations from Plato showed Symonds, as well as us, how real and vital was the passion of Greek love. Symonds even says, “It would be difficult to find more intense expressions of affection in modern literature” (Greek Ethics vii).

For reference:

Plato (428-348 BCE) was an ancient Greek philosopher, student of Socrates, teacher of Aristotle, and author of many philosophical works. In the Symposium, the characters discuss the topic of Love: interpersonal relationships through love, what types of love are worthy of praise, and the purpose of love. In the Phaedrus, the characters Lysias and Socrates present speeches on erotic love, the immortality of the soul, rhetoric, and the madness of love.

Title image: Anselm Feuerbach, Plato’s Symposium, 1869. Oil on canvas, 598 cm x 295 cm. From the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe via Wikimedia Commons.

Works Cited:

Featured image “The Banquet of Symposium” by Anselm Feuerbach (1869). Oil on canvas, Kalrsruhe, Germany. Wikimedia Commons.

Johns Addington Symonds (1840-1893) and Homosexuality. “Chapter 2: A Problem in Greek Ethics.” Palgrave Macmillan Publishing. Basingstoke, 2012. Print.

The Letters of Johns Addington Symonds. Wayne State University Press. Detroit, 1967. Print.

Symonds, John Addington. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Palgrave Macmillan Publishing. London, 2016. Print.

One thought on “Symonds’ Self-Revelation in Plato’s Ideal Masculine Greek Love”