It was the year 1872 and Symonds was 32 years old. After falling ill with possible tuberculosis in 1868, he had returned to lecture at Clifton College, and he began preparing essays such as that comprised the Introduction to the Study of Dante (1872) and Studies of the Greek Poets (1873-1876) as resource materials for teaching his classes.

He tells how he prepared these essays that summer in Austria: “I wrote the bulk of these lectures in a little tavern at Heiligenblut during the month of June, and remodeled them at Clifton” (Memoirs 438).

The chapters included in his Introduction to the Study of Dante were originally meant to make the study of Dante’s works more accessible to English readers. It was published in London in 1872, by Smith and Elder, a British publishing company that also published Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. This book is a precursor to his culminating work on the cultural history of the Italian Renaissance, entitled Renaissance in Italy, which appeared in seven volumes between 1875-1886. Dante was an important to Symonds as both a literary and historical figure.

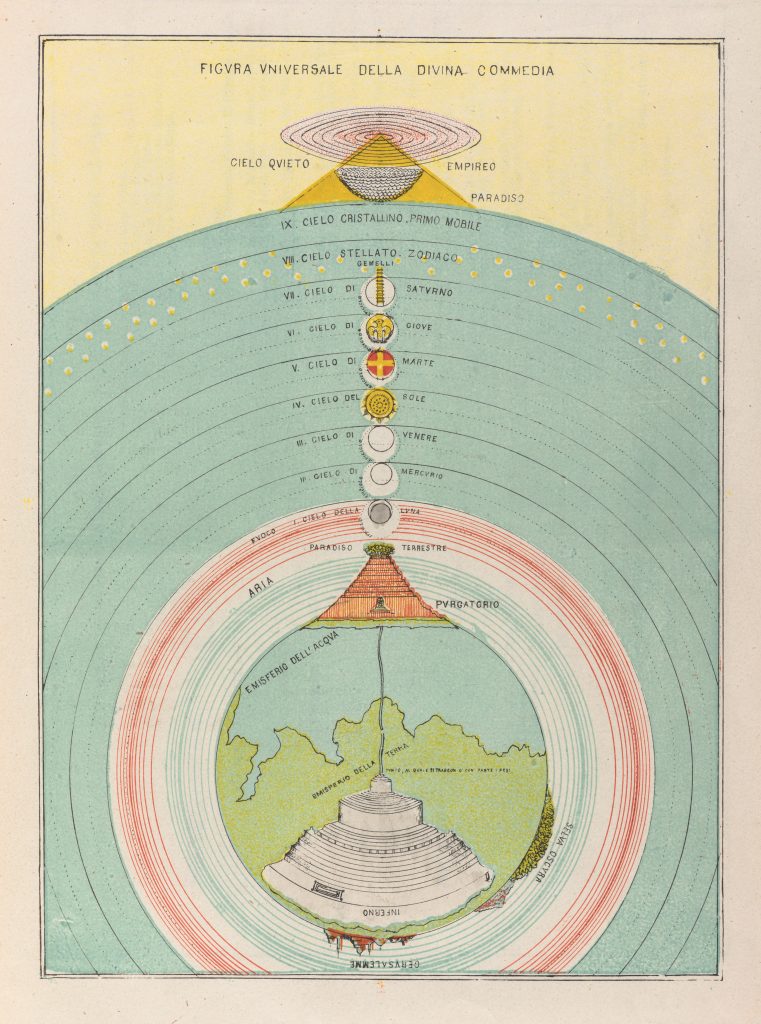

In his Introduction to the Study of Dante, Symonds begins broadly, writing first about early Italian history in the 13th century, then about Dante’s life in Florence: his literary studies, political quarrels, his relationship with Beatrice, and his exile from the city. Chapters 4 and 5 involve themes of the Divine Comedy – its allegory, satire, literary allusions, and the visual map of the Christian afterlife. Chapters 6 and 7 focus on Dante’s genius – the sublimity of his meter compared to Homer, Aeschylus, Shakespeare, and Milton and how it has influenced the later work. Chapter 8 discusses the differences between Classical Platonic love and Medieval chivalrous love, referencing Dante’s love poetry to Beatrice.

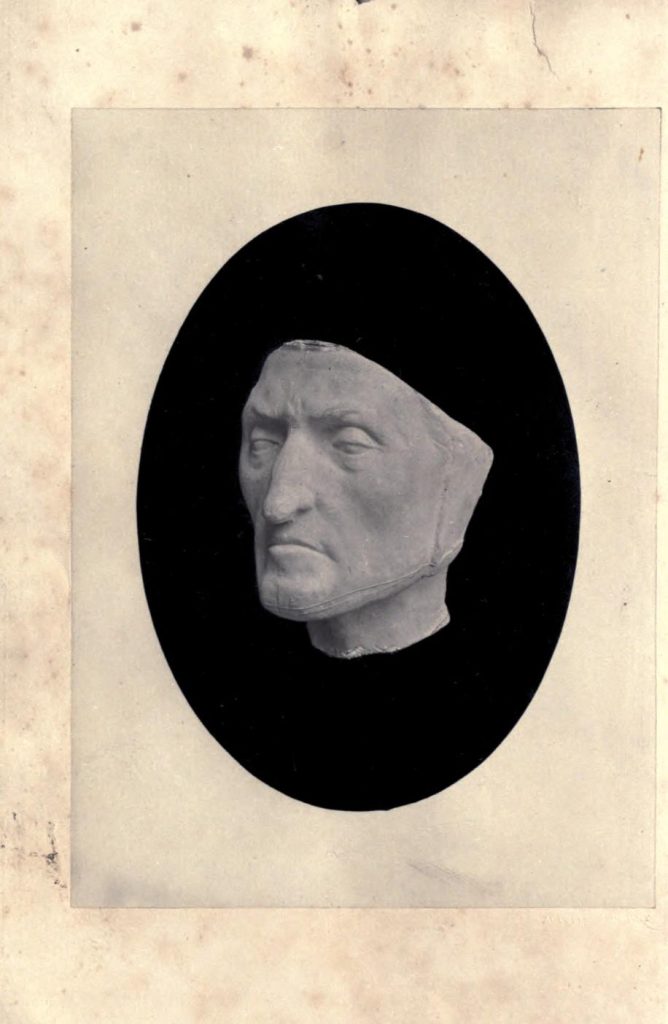

The photograph that serves as the book’s frontispiece is taken from a cast of Dante’s face in death which was given to Symonds by Mr. Kirkup of Florence, to which he ascribes physiognomic characteristics:

“The eyes are half-closed, as in death. The mouth is shut as though silence or paucity of words habitually dwelt upon the lips. The whole face is very calm and sad and grave”

(Introduction 88)

Dante was an important figure for Symonds, both in his studies and also in his personal life. While writing in London, Symonds first turned to Dante for words to describe his own sorrowful malaise and sexual repression. In a letter to Henry Sidgwick, he writes

“But at times, when my nervous light burns low in solitude, when the fever of the brain and lung is on me, then the shadows of the past gather round, and I feel that life itself is darkened…I am often numb and callous; all virtue seems to have gone out of me, the spring of life to have faded, its bloom to have been rubbed away. I dread that art and poetry and nature are unable to do more for what Dante with terrible truth called li mal protesi nervi” 1

(Memoirs 316)

His mental suffering reached a peak during his last few weeks at Cannes, France in 1869 when he contemplated suicide. He likened his own senseless desperation to Dante’s slothful in the fifth circle of Hell:

“Fixed in the mire they say, ‘We sullen were

In the sweet air, which by the sun is gladdened.

Bearing within ourselves the sluggish reek’ ”

(Inferno 7.121-3)

In December 1868, Symonds was introduced to Norman Moor, with whom he delighted in romantic affection. But while Norman reciprocated Symonds’ feelings in part, they never attained the Greek ideal union of lover and beloved, causing great pain for Symonds.

“The result was that I had to suffer from jealousy, from the want of any definite hold upon my adored friend, from the dissatisfaction of incomplete spiritual possession, and from the hunger of defrauded longings” (Memoirs 381).

The medieval trope of courtly love was one with which Symonds was familiar, both in his studies and in his personal homosexual endeavors. It is quite possible that Symonds likened his courtly love to that of Dante’s love for Beatrice.

In the summer of 1872, Symonds vacationed with Norman around Europe, and they reach a mutual unspoken agreement that the time for “amorous caresses” had gone by, yet Symonds still held a tender affection for him.

Right after their foreign tour, on September 19th, 1872, Symonds received his first published copy of the Introduction to the Study of Dante. He cited the publication of this book and the natural end of his episode with Norman as happening concurrently; one bitter ending brings another exciting beginning:

“Thus my entrance into authorship took place exactly at the moment when a final reconciliation of opposites was effected in the matter of my love for Norman. He became a schoolmaster, married, and is now the father of children” (Memoirs 402).

Besides the Newdigate prize poem on the Escorial (1860) and the Chancellor’s prize essay on the Renaissance (1863), Symonds had not yet published anything with his name attached to it until this essay.

In February 1871, his father died, never knowing a world where his son was a known author. Just a year later, in the spring of 1872, Symonds rose to literary success and published his lectures of Dante, which were “favourably received upon the whole, and added to my reputation” (Memoirs 439).

Symonds then compared the physical, sensual passion of Classical love poetry to the love of medieval, chivalric poetry – the amorous devotion heightened to religious worship:

“God was the ultimate object of the worship of the chivalrous lover; but the lady stood between his soul and God as the visible image and perpetual reminder of the heaven to which he ardently aspired. Thus Petrarch and Dante both constantly repeat that it was the thought of their lady which had ennobled them, and turned their souls to God” (Introduction 243).

The state of feeling generated by this love was called Joie; it was the ecstasy which filled the heart of the true lover with delight and capable of deeds almost more than mortal. Like the ideal Greek love Symonds so ardently desired, chivalric love existed independent of the marriage-tie; the lady who inspired it was often already married or otherwise unattainable. Symonds compares this courtly love to the mania of Greek love described by Plato in the Phaedrus, in which love led the way to heaven and raised a man above himself. Both the Classical and medieval chivalric love are idealized states, for which Symonds spent his life looking.

“Both set forth an idea of love, pure from the grossness of the flesh, not to be confounded with matrimonial affection or sensual passion, by means of which the spirit of man is rendered capable of self-devotion and high deeds” (Introduction 245).

While Symonds ultimately does not find his Beatrice in Norman, he does go through a harrowing pilgrimage of his own during the writing and publication of An Introduction to the Study of Dante. Just as Dante enters the darkness of the underworld scared and confused2 only to find his way up to the blessed salvation of Heaven,3 Symonds begins 1871 lost and depressed, having just suffered the loss of his father, but ends 1872 with the publication of his first official book and a renewed sense of creativity.

For reference:

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) was an Italian statesman, political theorist, and poet of the Late Middle Ages. He is most known for his Divine Comedy, an allegorical poem writing in the Italian dialect that depicts Dante the pilgrim’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. He is cited as an influence on John Milton, Giovanni Boccaccio, Geoffrey Chaucer, and Alfred Tennyson among others for his literature and theology. He also published the Vita Nuova (The New Life}, a book of verse poems detailing his tragic, unrequited love for Beatrice. He immersed himself in the politics of Florence, where he fell out of favor and was exiled for life by leaders of the Black Guelfs.

1 “sin-excited nerves” (Inferno 15.114).

2 “I found myself within a forest dark / For the straightforward pathway had been lost” (Inferno 1.2-3)

3 “But now it is turning, my desire and will / the Love which moves the sun and the other stars” (Paradiso 33.143-145).

Featured image: Gustave Dore, “Inferno Canto 6.” From Dante Alighieri, The Vision of Hell. Trans. Rev. Henry Francis Cary. London: Cassell, 1892. From Project Gutenberg via Wikimedia Commons.

Works Cited:

“Dante Alighieri – The Life.” Unione Fiorentina, Museo Casa di Dante, 2018. Website. Digital Access.

Symonds, John Addington. An Introduction to the Study of Dante. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1872. Internet Archive, University of California Libraries SRLF 302444. Digital Access.

Symonds, John Addington. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Amber K. Regis, editor. London: Palgrave Macmillan Publishing, 2016. Print.

N.B. The translations of Dante’s Divine Comedy that Symonds cites in his Memoris are from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1867). Columbia University, Website. Digital Access.

One thought on “The Years 1871-1872, or Symonds’ Dantesque Pilgrimage”