One of the lab’s tasks for this semester included extracting data for the Lost Library from the letters of John Addington Symonds. Working with this new source of evidence has raised new questions: How can we determine degrees of book ownership? How can we be certain Symonds owned a specific edition of a work? Can different non-book printed materials such as a photograph or a libretto count as a new entry? All these matters have prompted us to reexamine how we add evidence to the Lost Library and how we justify our decisions.

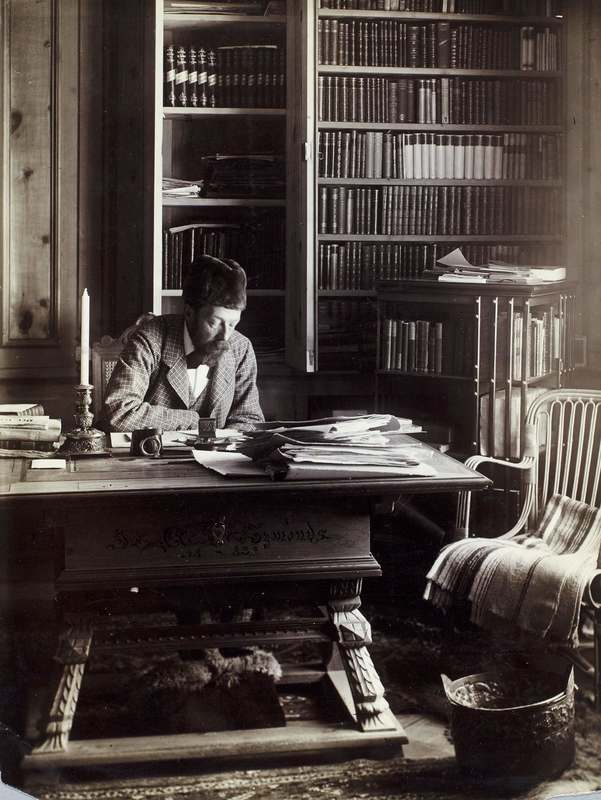

For earlier lab cohorts, the main sources of evidence for books to include in the Lost Library included the entries from auction catalogs (created when books from Symonds’s library were sold) and titles Symonds mentioned in his Memoirs. A few works were also recorded by analyzing a large-scale photograph of Symonds in his study and reading the titles from the book spines. These methods allowed for strong confidence in our knowledge regarding the books Symonds owned or read.

Extracting data from the Letters has posed new challenges that our cohort has worked through. Students read through each letter and recorded titles mentioned, relying primarily on the footnotes provided by editors Herbert M. Schueller and Robert L. Peters for details. Some footnotes provided enough information for a researcher to find the work that was in Symonds’s collection or that he read. However, sometimes we encountered titles mentioned in passing within a letter with little to no information with regards to edition, publication, or ownership status–raising questions about the best practices for recording such works and how, or whether, to include them in the Lost Library. As mentioned, our new inquiries include deciding which edition of a work to list if it is unclear, defining the boundaries of the types of materials in the library, and deciding on the degree of ownership and importance a given work has.

The group has articulated a few standard practices regarding the choice of an edition if one is not listed in the footnotes. Students originally adopted the practice of locating the first edition of the work we could find (choosing an edition published in London over an American publication), though recent practice has been to prefer instead the prior edition closest to the date of the mention. There were also issues about choosing editions for famous works in the literary canon, such as a Shakespeare play or books of the Bible. In these cases, we are still not sure if Symonds had a specific Shakespeare collection or Bible he frequently read. In some cases, we can narrow down the options. For example, we can deduce that the family Bible the Symonds household most likely read was the King James Version. We have left such works to the side for now, and we hope to find more evidence in the future that will point towards which editions of these works the author most likely owned.

Another subject that frequently came up was what material types are allowed in the Lost Library. A student might find a reference to a photograph or painting that seemed important to Symonds, but prompted greater questions about how we define the scope of the library. In one discussion, a student brought up a question about a libretto for Franz Joseph Haydn’s oratorio The Creation (composed in the 1790s) that Symonds wrote about in a letter. The student recorded that Symonds saw the renowned British soprano Clara Novello perform the oratorio. After discussing the work with the team, the researcher couldn’t confidently deduce that Symonds owned a physical copy of the libretto. However, questions remain about the influence that this and other artistic or musical works had on the author. The Creation surely must have had a great effect on the author for him to mention it. If he had a copy of the libretto, he very well could have stashed it in his physical library. These uncertainties about different material types make us re-think what the Lost Library is. Should the collection include any work that we think was important to Symonds? We defined the boundaries of the library to focus mainly on books that we know he owned or that we can justify were important to him. However, the significance of other mediums such as music, art, and photography are interesting subjects that can be explored in depth in the future.

Lastly, some of the most interesting conversations arose around questions about degrees of ownership and the importance of a book to Symonds. Is his ability to quote excerpts from a work by heart a sign of ownership? Does this ability mean that the work had a profound impact on him? Is his expression of interest in purchasing a book from the shop an indication of potential ownership? When grappling with such questions, students had to find convincing evidence in the letters that made us think he owned a book or if it greatly impacted him in some way. The justification of our decisions whether to include a work or not has sparked many conversations about addressing the question of ownership as we have generated data for the library.

Despite these challenges, examining the Letters gave our group a nuanced view of Symonds’s literary interests and influences. As our team talked about during our final discussion, studying them has allowed us to truly appreciate the variety of works the author engaged with during his lifetime. Reading a firsthand account of books he found interesting during a trip or what was popular in his day has allowed us to value the rich diversity of his library, beyond what an auction catalog can offer. Our group of researchers was able to join Symonds on his literary journey as we read through his letters. We found works ranging from serial magazines to schoolbooks that he engaged with as a young man and growing author. Finally, the efforts of our cohort to define best practices when investigating the Letters should prove helpful to future researchers and should give readers an understanding of our process. We look forward to finding what insights into the literary life of John Addington Symonds the remaining volumes of the Letters have to offer.