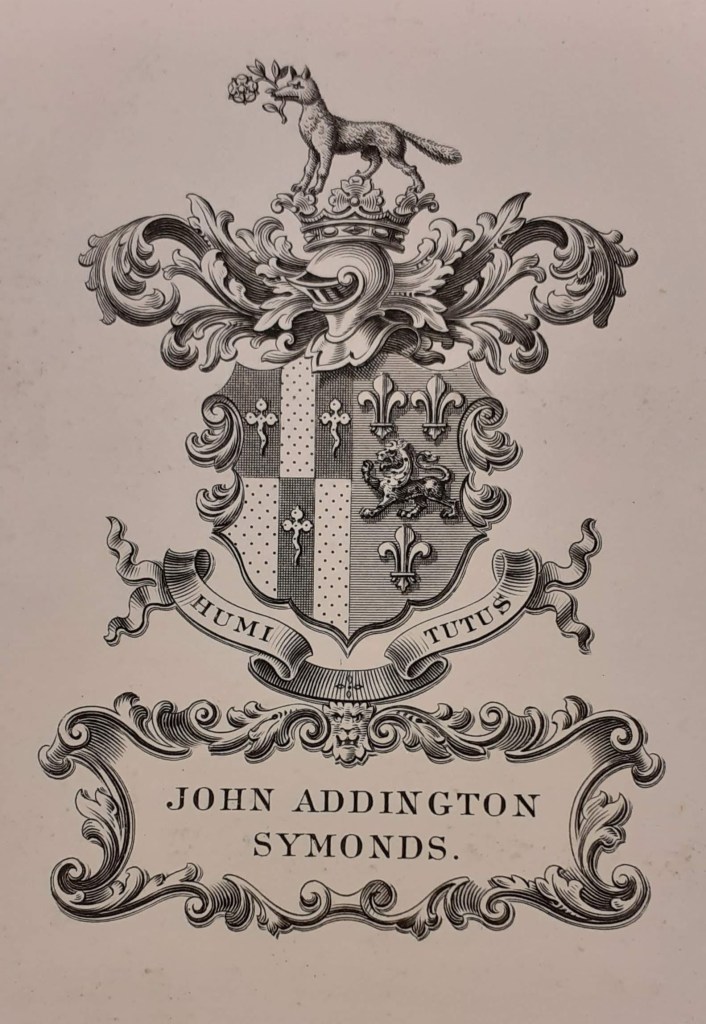

After spending time thinking about Symonds’s name and family history in my previous post (entitled “What’s in a name?”), I decided to continue along the same theme with this one. Within the Johns Hopkins University Special Collections Library appears a copy of Agamemnon: A Tragedy taken from Aeschylus that was translated by Edward FitzGerald and owned by both Symonds and William W. Gay, as evidenced by their bookplates in this copy. This book and the bookplates found within it offer several branches of research. One is Symonds’s relationship to the text itself, which has already been explored in a post by another student (visible here). Another branch explores which of these men owned this book first and thus who was given it “With the publisher’s compliments”–a manuscript inscription that appears on the front endpaper. This mystery was solved after I had the chance to read a letter, laid into this copy, from the publisher, Bernard Quaritch, to William W. Gay, dated November 5, 1912. In this letter, Quaritch explains the differences between the edition of FitzGerald’s Agamemnon that was privately printed in 1865 and the one Quaritch himself published in 1876. The fact that this letter was written nearly two decades after Symonds’s death and Gay’s need for this explanation suggest that Symonds was the original owner of this book. While this is fascinating information, as a student of art history, I was most interested in studying the bookplate itself.

The first step to deciphering this heraldic symbol was to understand the different elements represented on the bookplate. The Handbook to English Heraldry by Charles Boutell served as a resource for this research. Using this book, I learned not only the different colors and metals present on Symonds’s coat of arms but also the terms and some histories for the different heraldic symbols. To give a brief overview of terminology, coat of arms refers to “a complete armorial composition” (Boutell 1914, 109). This encompasses not only the shield of arms or shield, which derives its name from the battle-shields that would have once been decorated, but also the helm or helmet and the crest both of which are found atop the shield (Boutell 1914, 32, 133, 128-129). Any supporters, or figures that appear alongside the shield, that might exist are also considered part of the coat of arms (Boutell 1914, 152-153).

Figure 1

With this information, we can begin to decipher the coat of arms present on the bookplate within Agamemnon (Figure 1). The animal present in the Symonds family crest is identified as an ermine by Symonds (1894, 28-29). This ermine is standing on four paws, looking forward, a position termed statant in heraldry (Boutell 1914, 85). In its mouth appears a rose that, according to Symonds (1894, 29), should be red and have green leaves. The crown supporting this crest is called a crest-coronet in heraldry (Boutell 1914, 113). This sits atop the helm of a gentleman, which is always steel-colored and which appears with “the vizor closed, and set in profile” (Boutell 1914, 129). The next element of the coat of arms is the shield. When using proper heraldic terminology, the shield depicted in Figure 1 can be described in the following terms: per pale; sable and or counterchanged, three trefoils slipped of the second on the dexter side; azure, three fleurs-de-lys argent, passant lion or on the sinister side. In layman’s terms, that means that the shield is split down the middle into two parts. On the left-hand side, there is a black and gold checker-board-like pattern on which three, gold trefoils appear in a specific design. On the right-hand side, the background is blue and three, silver fleurs-de-lys appear alongside a gold lion. To assist in visualizing this colorful coat of arms, see Figure 2. Any heraldic symbol lacking a described color (e.g., the ermine and the crest-coronet) is meant to appear as it would in real life. Given that a stoat is only called an ermine when wearing its winter coat, its coloring is white with a tail terminating in black (“Ermine”). The crest-coronet, however, can have many color variations. Also note that the artistic flourishes to the coat of arms do not appear in color in this depiction.

Figure 2

Another element generally included in a coat of arms is a motto, which oftentimes in heraldry serves as a pun on the family name (Boutell 1914, 138). For example, while the family motto on Symonds’s bookplate is “Humi tutus,”2 Symonds wrote in On The English Family of Symonds the following:

My father invented a motto: ‘In mundo immundo sim mundus3,’ which plays upon the family name as we pronounce it. A friend of mine suggested that this might be improved into: ‘Si mundus immundus sim mundus,’ which plays upon the two pronunciations of the name.”

John Addington Symonds, On The English Family of Symonds (1894, 30)

This play on names is quite common in heraldry according to Boutell (1914, 138). Interestingly, in his adulthood, Symonds (1894, 30) “ha[d] little to say” about his family’s motto only touching upon the suggestions of his father and his friend; however, the same can not be said for a much younger Symonds. As a teenager, Symonds became interested in his family genealogy and heraldry. Symonds’s own assessment of this research and of his family motto appear in a letter to his sister, Charlotte. Symonds wrote:

My inner life has been much perturbed on genealogical subjects, owing to the booklabel which Bosanquet bought me. It is a regular heraldic enigma. How cruel our Ancestors were not to pay more attention to their colours & metals! One thing settled is that our crest is correct with the substitution of a red rose for the cinquefoil. Joshua S. the surgeon of London must have been an unaspiring individual as his motto is “Humi tutus.” I wonder whether he wished to transmit this grovelling sentiment to his descendants! If so, he has been frustrated as we have certainly made a change for the better.”

Letters 1:131 (58) to Charlotte Symonds (Harrow January 17, [1858])

This excerpt is interesting for several reasons. Not only does he mention his bookplate, or at least this very first one, as being a gift—most likely from his “bosom-friend at Harrow,” Gustavus Bosanquet (Symonds 2016, 140)—Symonds also mentions that it was this bookplate that, in part, led to his interest in his family genealogy and heraldry. Further, Symonds’s early assessment of “Humi tutus” as both “unaspiring” and “grovelling” greatly contrasts with his later, seemingly disinterested stance on the subject.

Now that all the elements of Symonds’s coat of arms have been discussed, there is an interesting twist to this story: Symonds believed the coat of arms present on the bookplate to be inaccurate. In fact, Symonds (1894) dedicates a significant portion of On The English Family of Symonds not only to the history of the family coat of arms but also to a series of corrections the shield should have. In his opinion, “the proper arms and crest of my own immediate family” would have a shield designed with the following specifications:

Quarterly 1 and 4: per fess sable and or, a pale counterchanged, three trefoils slipped of the second: 2 and 3 azure three trefoils or. […] Crest, on a ducal coronet an ermine statant holding in his mouth a rose gules stalked and leaved vert.”

Symonds 1894, 28-29

According to Symonds, while the crest is accurate, the shield that appears on the bookplate would need several corrections. First, the shield should be split into four separate parts with each diagonal pair sharing the same characteristics. The top-left and bottom-right sections of the shield should have the same black and gold pattern that appears on his bookplate as well as the same three, gold trefoil designs. The top-right and bottom-left sections should have a blue background and three, gold trefoils rather than three, silver fleurs-de-lys. There is no mention of a lion in this design. Figure 3 creates one possible rendition of this “proper” coat of arms, though positioning for the gold trefoils on the blue background can be varied. Note again that the colors chosen for the crest-coronet can also vary.

Figure 3

The differences between the coat of arms on the bookplate in the Johns Hopkins University collection and the one that Symonds considered correct carry with them one important question: did Symonds ever change his bookplate to match the proper coat of arms? While I have only come across this one design in my own research, it does appear that at least two versions of his bookplate might exist. After all, as a teenager, Symonds wrote that there was a “cinquefoil” present on the crest of the coat of arms that should be replaced by a “red rose” (Letters 1:131 (58) to Charlotte Symonds (Harrow January 17, [1858])). The bookplate in Agamemnon: A Tragedy taken from Aeschylus and in other works I have seen (e.g., The Life and Death of Jason: A Poem, in the Sheridan Libraries collection) includes this adaptation, so it is not impossible to imagine other changes occurring. Additionally, if there is not and never was a bookplate with Symonds’s corrections, that begs the question as to why the changes were never made. These questions are worth exploring in future attempts to understand Symonds’s relationship with his past and how it affected his present.

Endnotes:

1. My own description from heraldic information in Boutell.

2. Translated by Herbert M. Schueller and Robert L. Peters as “Safe on the ground” (Letters 1:132 (58) n4 to Charlotte Symonds (Harrow January 17, [1858])).

3. Translated by author as “In an unclean world, I am clean” using Harper’s Latin Dictionary (1907) edited by Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short, pp. 895, 911, and 1175.

4. Translated by author as “If the world is unclean, I will be clean” using Harper’s Latin Dictionary (1907) edited by Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short, pp. 895, 1175, and 1688-9.

References:

Boutell, Charles. 1914. The Handbook to English Heraldry. Edited by A. C. Fox-Davies. London: Reeves & Turner. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/23186/23186-h/23186-h.htm.

“Ermine.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Last modified June 6, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/animal/ermine-mammal.

Harper’s Latin Dicitonary, ed. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. `1907. New York, Cincinnati, and Chicago: American Book Company.

Morris, William. 1868. The Life and Death of Jason: A Poem. London: Bell and Daldy. From Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University.

Quaritch, Bernard. Bernard Quaritch to William W. Gay, November 5, 1912. Letter. From Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University.

Symonds, John Addington. 1894. On The English Family of Symonds. Oxford: Privately printed. Google Books. https://www.google.com/books/edition/On_the_English_Family_of_Symonds/sQMPAAAAQAAJ

Symonds, John Addington. 1967. The Letters of John Addington Symonds. Edited by Herbert M. Schueller and Robert L. Peters. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Symonds, John Addington. 2016. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Edited by Amber K. Regis. London: Palgrave Macmillan.