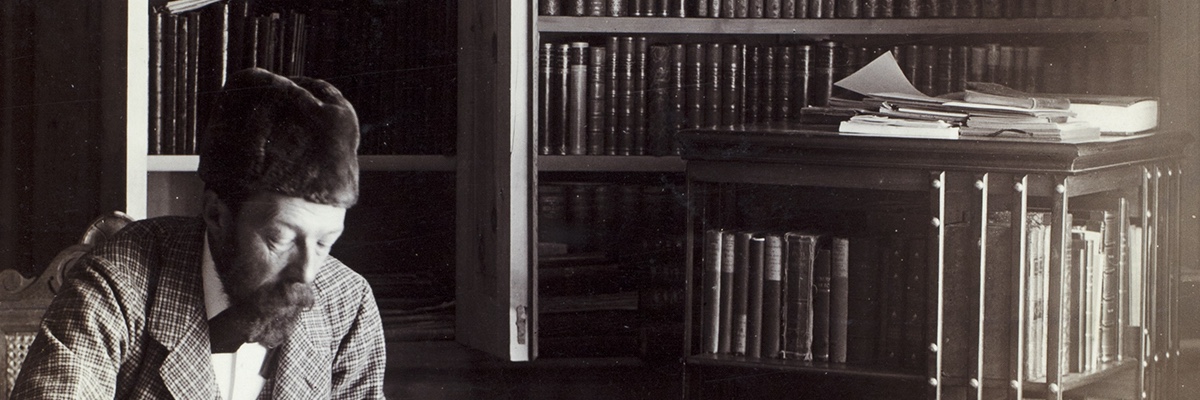

In his Memoirs, Symonds wrote that his “house was well stocked with engravings, photographs, copies of Italian pictures and illustrated works upon Greek sculpture” and more. He considered “the two large folios issued by the Dilettante Society” as “among his chief favorites” (118). The Society of Dilettanti, the group of men that compiled such collections, was founded in 1734 and consisted of young, educated Brits who had been on a so-called “Grand Tour” of Italy, as was fashionable at the time. The impact of the collections of engravings and sculptures that they published is evidenced by Symonds’ passion for consuming such compilations and, later, his own time abroad in Italy.

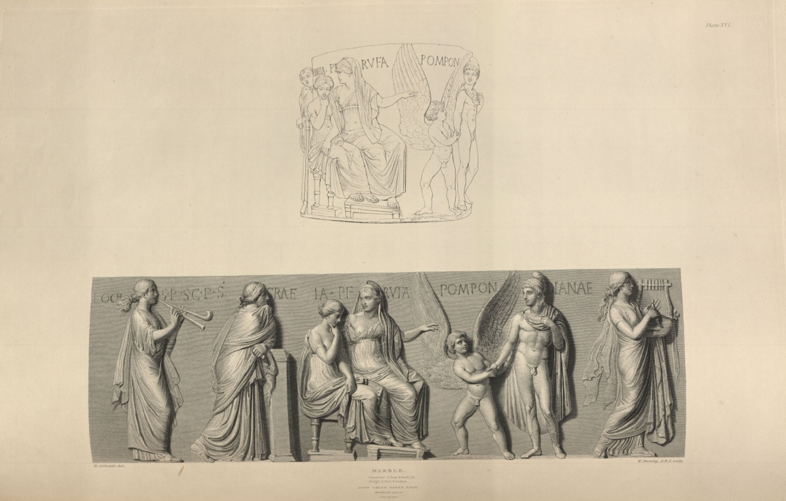

The image above is a unique art object featured in one of the Society’s catalogs. While it shows a relief that currently adorns a vase, the work was believed by the Society to have originally been a Περιστομιον, a decorative engraving around the mouth of a well. It portrays the introduction of Paris to Helen by Venus, who shares in the task with the three muses, Polyhymnia, Erato, and Euterpe, and, of course, Love himself (as personified by the winged boy) (31). The presence of this Cupid-like vision of Love is what makes this image particularly striking, as we know from Symonds’ memoirs that he was so enraptured with Plato’s the Phaedrus and the Symposium, two of the most well-known dialogues on the subject of love,that he read them in one-sitting, until “the sun was shining on the shrubs outside the ground-floor room in which I slept” (152).

Today, while they may take on new forms like Instagram poetry or advice columns, conversations surrounding the nature of love live on and retain the power to offer us perspective that help us to feel less alone. One hotly debated topic remains whether or not falling in love is something we can control. In their description of the image above, the Society of Dilettanti writes that “the conduct of Helen is invariably represented as the effect of an irresistible destiny” (Specimens). In other words, Helen’s position, surrounded by those conspiring to make her fall for Paris, leaves her vulnerable; there is nothing she can do to resist her fate. Interestingly, in his Memoirs, Symonds expresses a similar lack of agency, writing that his “enthusiasm for male beauty” has “ruled him from childhood” (152).

While this image portrays Love acting upon a man and a woman, we can imagine Symonds identifying with the kind of experience of an all-encompassing, undeniable attraction depicted. This is all the more powerful when considered in conjunction with Plato’s Symposium, especiallyPausanias’ argument that “there is dishonor in yielding to the evil, or in an evil manner; but there is honour in yielding to the good, or in an honourable manner” (181a). Helen herself may have met a dire end, but the Symposium emphasizes that so long as one’s love is characterized by noble qualities, succumbing to the influence of its larger-than-life power can better both of the parties involved. As Symonds writes, through reading this ancient text, he realized the “moral charm” and “sublimity” in the love he shared for other men and, in this way, discovered a means of beginning to find “harmony” (152).

Works Cited

Dorment, Richard. “The Dilettanti: Exclusive Society That Celebrates Art.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 2 Sept. 2008, www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/3559589/The-Dilettanti-exclusive-society-that-celebrates-art.html.

Plato. Symposium, Translated by B. Jowett, 2013. Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1600/1600-h/1600-h.htm.

Specimens of Antient Sculpture, Ægyptian, Etruscan, Greek and Roman: Selected From Different Collection In Great Britain. London: Printed by T. Bensley for T. Payne, and J. White and co., 1809.

Symonds, John Addington. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Edited by Amber K. Regis. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.