Karl Heinrich Ulrichs’ series of twelve pamphlets, Forschungen über das Rätsel der mannmännlichen Liebe (“Research on the riddle on male-male love”), published between 1864 and 1870, comprise a seminal work in the history of sexuality. For Symonds, Ulrichs’ texts lay the foundation for his understanding of “sexual inversion,” the more common term and concept before they were supplanted by “homosexuality,” which Symonds himself was the first to borrow from the language of German sexologists.

Symonds references the idea of “Urnings,” a term that Ulrichs uses to describe men who are attracted other men. In particular, Symonds references “Uranian Love,” as it is described in Plato’s Symposium, in A Problem in Greek Ethics:

“The offspring of the heavenly Aphrodite is derived from a mother in whose birth the female has no part. She is from the male only; this is that love which is of youths, and the goddess being older, has nothing of wantonness.”

(Plato, Symposium 181, trans. Jowett, quoted in Symonds, Greek Ethics XIII)

The etymological origin for the term “Urning” is Uranus, based on the idea that Aphrodite’s origin is from Uranus’s testicles, as Plato explains in the Symposium. For Ulrichs, Urnings “form a sex apart—having literally a feminine soul included within a male body,” in reference to Aphrodite’s contrasting lineage and form (Symonds, Sexual Inversion, 102). This framing is epitomized by the “woman in male form” motif in Ulrichs’ explanation of sexual inversion. Ulrichs’ use of a classical framework resembles Symonds’ use of a classical framework in his Memoirs. Symonds states that:

Our earliest memories of words, poems, works of art, have great value in the study of psychical development.

(Memoirs, 101).

For Symonds, classical art provides a place where an analysis of the kind that all of the sexologists of his day try to do with psychological theories because it focuses on the individual lived experience. The response to art—in Symonds’ case, art from classical antiquity—provides an insight into what Symonds perceives as the ideal form of human relationships. Most psychological studies of Symonds’ time dealt with explanations of phenomena like sexual inversion from the outside looking in, figuratively speaking, by using theoretical models to explain behaviors. Symonds inverts that paradigm, by building out from experience toward a larger theory of sexology. When one views artistic depictions of bodies, there can be an underlying sexual reaction to the artistic representation of the body.

In A Problem in Modern Ethics, Symonds references Ulrichs as the first scholar to offer “serious and sympathetic treatment” of the topic of sexual inversion (159). For Symonds, Ulrichs “proceeds to argue that the present state of the law in many states of Europe is flagrantly unjust to a class of innocent persons, who may indeed be regarded as unfortunate and inconvenient, but who are guilty of nothing which deserves reprobation and punishment” (ibid. 159). In large part, Symonds agrees with Ulrichs’ view of the legal oppression of same-sex relations, and in that sense, Symonds sees Ulrichs as one of the first scholars to take a more research-based approach to the issue.

Symonds notes that the German lawyer wrote his pamphlets with the intention of establishing “a theory of sexual inversion upon the basis of natural science, proving that abnormal instincts are inborn and healthy in a considerable percentage of human beings” and therefore “that they do not owe their origin to bad habits of any kind, to hereditary disease or to wilful depravity” (ibid. 159).

Symonds argues that of the twelve pamphlets that were published, the seventh is the one that introduces the major concepts of Ulrichs’ theories: “Memnon may be used as the textbook of its author’s theories” (ibid. 159). In his seventh pamphlet “Memnon,” Ulrichs states that:

“The primitive hermaphrodite is reshaped into an Urning. There arises a man, but not in the strict sense, endowed with a female sexual drive, who, therefore, although he has testicles, feels himself attracted through the inner sexual drive, not to women, but to (young) men, hence an Urning.”

(Ulrichs 303)

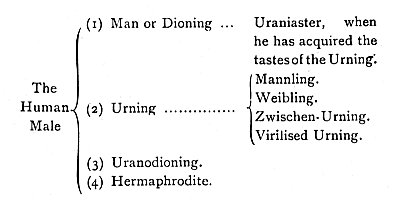

Ulrichs’ theory then splits the Urning into different types, distinguished based on the behaviors of the Urning: “the Mannling and the Weibling. Mannlings’ physical characteristics…are completely masculine; only the bare mental sex, the direction of the yearning towards the male sex, is feminine,” while Weiblings are physically and sexually “completely feminine; only the biological sex is masculine” (ibid. 306). To these basic categories he added a series of subcategories and hybrid categories.

Symonds relates to Ulrichs’ sexological theories at a personal level, not just on an academic level. “With regard to Ulrichs, in his peculiar phraseology, I should certainly be tabulated as a Mittel Urning , holding a mean between the Mannling and the Weibling ; that is to say, one whose emotions are directed to the male sex during the period of adolescence and early manhood; who is not marked either by an effeminate passion for robust adults or by a predilection for young boys” (Memoirs , 103).

While Ulrichs’ influence on Symonds can been seen in his understanding of sexual inversion and the common connection with the classical framework of Uranian love, Symonds was by no means completely in agreement with Ulrichs. In his Memoirs, Symonds notes some of these disagreements and explains his own understanding of sexual inversion: “It does not appear to me that either Ulrichs or the school of neuropathical physicians have solved the problem offered by individuals of my type” (102). Specifically, Symonds agrees with Ulrichs’ general hypothesis about the natural origin of sexual inversion, but he sees a disconnect between Ulrichs’ theories and his own lived experience and personal view of idealized love between men.

As a result of his disagreement with previous scholarship on sexual inversion, Symonds argues “that the abnormality in question is not to be explained either by Ulrichs’s theory, or by the presumptions of the pathological psychologists. Its solution has to be sought far deeper in the mystery of sex, and in the variety of type exhibited by nature” (Memoirs, 103). In other words, Symonds places himself as a descendant and a critic of the ideas put forth by previous scholars.

Works Cited

Plato. Jowett, Benjamin, translator. Symposium. MIT. Internet Classics Archive, http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/symposium.html.

Symonds, John Addington. Regis, Amber K, editor. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

Symonds, John Addington. A Problem in Greek Ethics. Sexual Inversion. Bell Publishing Company, 1984.

—. Symonds, John Addington. A Problem in Modern Ethics.

Ulrichs, Karl Heinrich. The Riddle of “Man-Manly” Love: The Pioneering Work on Male Homosexuality. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash, vol. 2, Prometheus Books, 1994.