From John Addington Symonds’ body of work, it seems clear that Greco-Roman art and literature had a significant influence on his intellectual and sexual development. In his memoirs he describes the books in his childhood home that were influential in his personal and intellectual life.

Sculpture specifically played a significant role in Symonds adolescence, as he came into his sexuality and discovered his attraction to men. In his memoirs, he discusses his early experiences of sexual dreams which allowed him to appreciate male beauty in art, writing that “this vision of ideal beauty under the form of a male genius symbolized spontaneous yearnings deeply seated in my nature, and prepared me to receive many impressions of art and literature”.1 He then specifically describes how a photograph of the Praxitelean Cupid was particularly inspiring: “A photograph of the Praxitelean Cupid…taught me to feel the secret of Greek sculpture…[and] strengthened the ideal I was gradually forming of adolescent beauty”.2 In this way, studying the masculine form in sculpture provided an outlet for his appreciation of male beauty, a concept important in his discussion of paiderastia in A Problem in Greek Ethics.

From his account of his childhood library, Symonds seems to have had access to a number of works focused on photographs and engravings of Italian and Greek art, and sculpture in particular.3 He directly mentions two folios of the Society of Dilettanti as being among his favorite sources of Greco-Roman art. With the emphasis Symonds places on sculpture, it is reasonable to conclude that one of the folios to which he is referring is

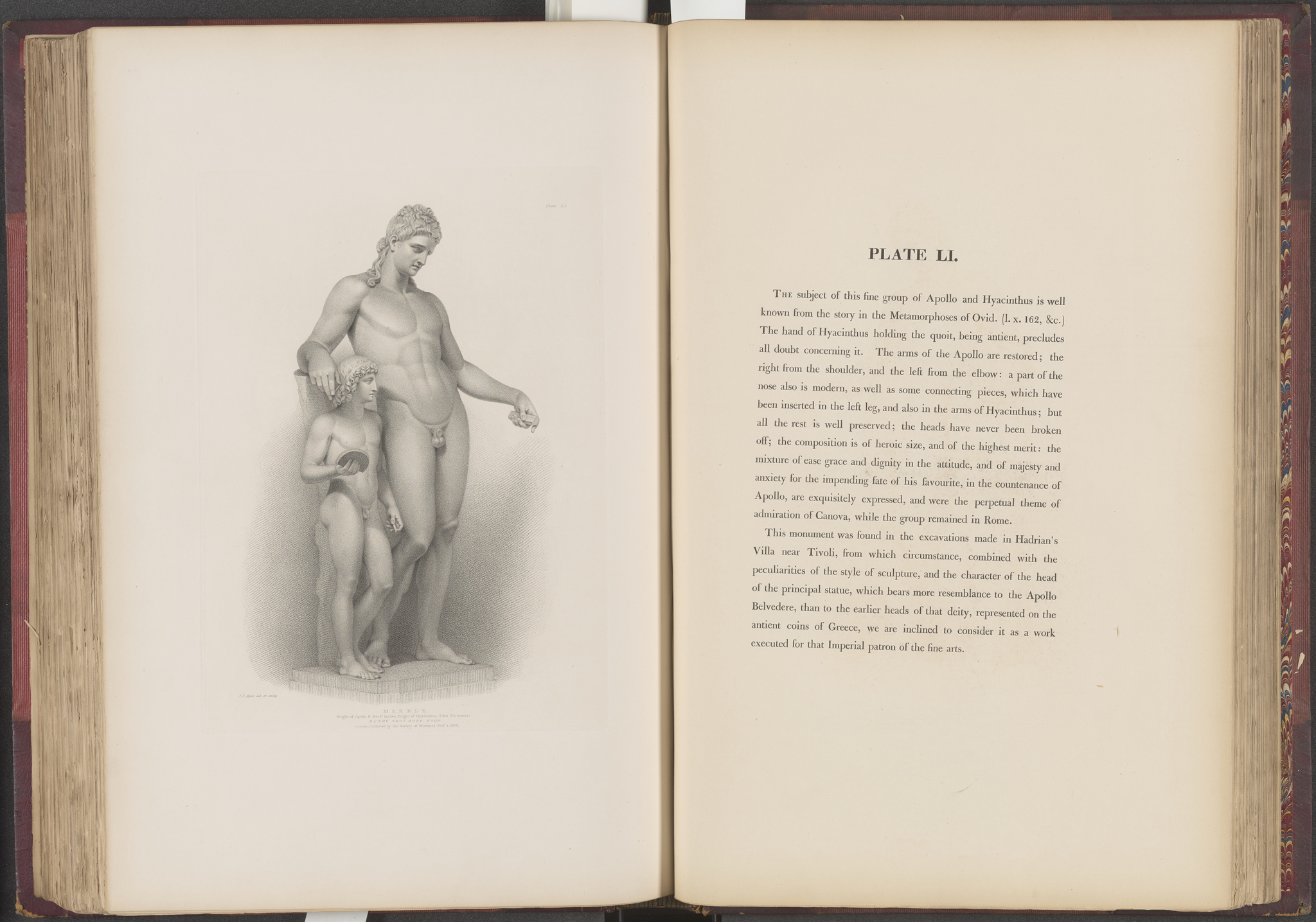

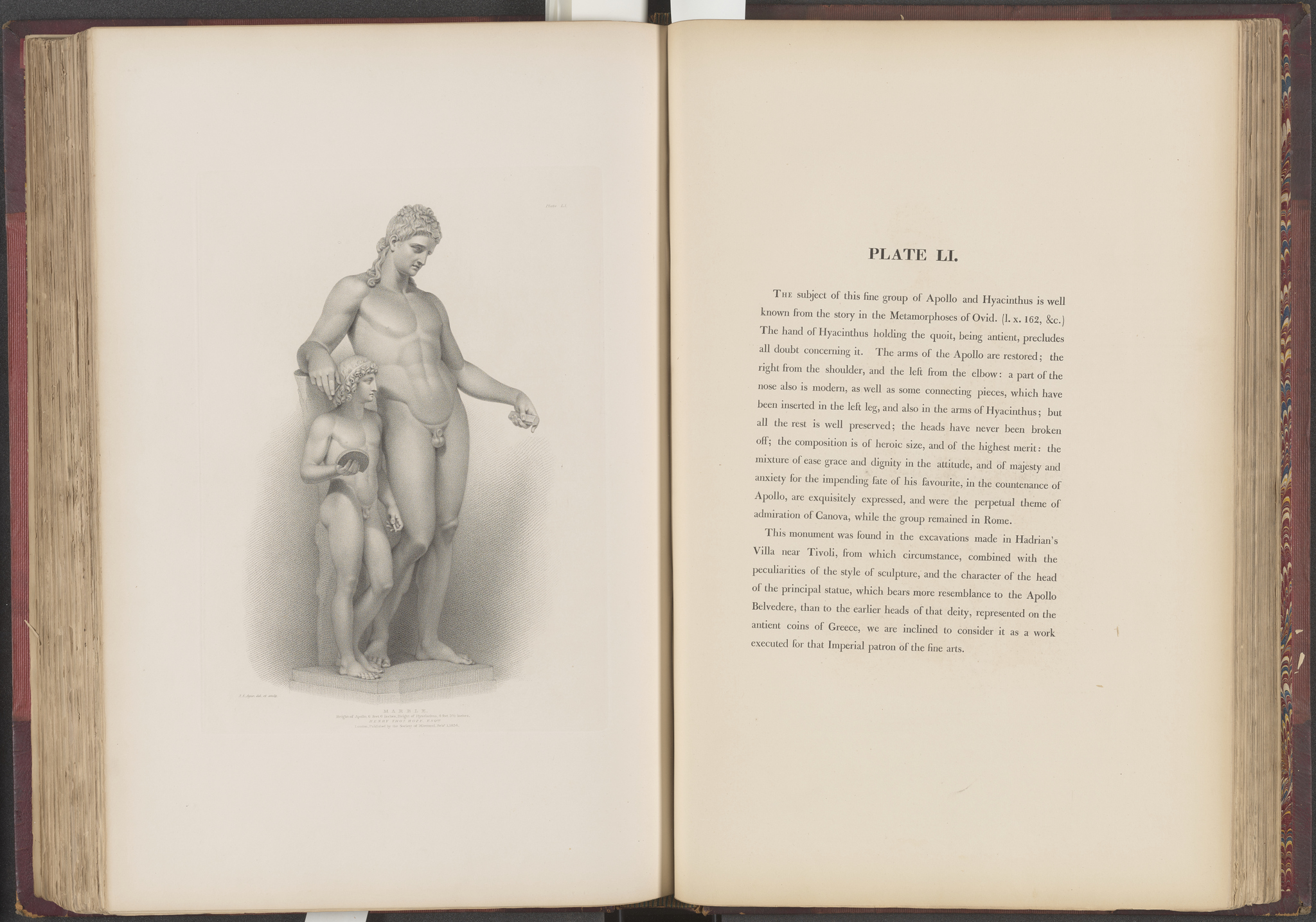

Specimens of antient sculpture, Ægyptian, Etruscan, Greek and Roman: selected from different collection in Great Britain. Published in 1809, it is likely that the folio gained popularity and became culturally significant for an educated man like Symonds, so that he would have read it in his youth and adolescence. Within the plate book are images of a multitude of sculptures representing men, women, and various scenes. While a number of images could have been meaningful to Symonds, a particular image was of note to me, shown below in Plate LI.

The image shows a sculpture of Apollo and Hyacinthus, likely from Hadrian’s villa near Tivoli—as noted in its description.4 The pair are known from the tenth book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which the two have a love affair that appears to be a paiderastic relationship, with Hyacinthus being a young boy in this loving and likely sexual relationship with an adult Apollo.5

“[Apollo’s] zither and his bow no longer fill

his eager mind and now without a thought

of dignity, he carried nets and held

the dogs in leash, and did not hesitate

to go with Hyacinthus on the rough,

steep mountain ridges; and by all of such

associations, his love was increased.”

The story takes a tragic turn when Apollo’s discus takes an unfortunate bounce off the ground, striking and killing Hyacinthus.6

“My own hand gave you death

unmerited — I only can be charged

with your destruction.—What have I done wrong?

Can it be called a fault to play with you?

Should loving you be called a fault? And oh,

that I might now give up my life for you!

Or die with you! But since our destinies

prevent us you shall always be with me,

and you shall dwell upon my care-filled lips.”

Beyond the context of the image, the details of the sculpture are worth noting. From the image in the plate book, the sculpture looks incredibly well-made; the figures look extremely lifelike, seeming less of marble and more of flesh and bone. Here we can see the idealism often associated with classical art, of perfect human form. It is no wonder the image served as a reinforcement of male beauty for Symonds. There also seems to be a tenderness in the figures’ poses, with Apollo’s hand resting on Hyacinthus’ hair and Hyacinthus’ arm on Apollo’s thigh, suggesting a sense of intimacy between the pair. Such a depiction of two men could have been extremely influential to Symonds and his burgeoning sexuality, providing a classical example of his own feelings towards men. These features, along with the mythological context, create the potential for a huge impact on Symonds, not only in understanding himself, but informing his future scholarship.

Such an image could have been very significant to Symonds, in helping him understand his own sexuality as well as the paiderastic relationships he would discuss in A Problem in Greek Ethics. He mentions Apollo and Hyacinthus across different works when discussing paiderastia and male friendship. In Letter 476 in Volume I of his Letters, he references the lovers when describing “the divine youths and maidens of Hellenic dreams…some Hyacinth bewept by Phoebus”.7 In Volume II of Studies of the Greek Poets, Symonds again references the pair when providing quick examples of tales describing male friendship in Greek mythology and history.8 The story was able to provide Symonds with more evidence of the prevalence of paiderastia within mythology and history to inform his position on paiderastia even further.

The tale of Apollo and Hyacinthus, the associated sculpture, and its image seem then to have had significant influence on Symonds on the development of his sexuality and insight into paiderastic relationships in mythology. The lovers’ different forms symbolize paiderastic love as well as masculine beauty, both of which are ideas which contributed to Symonds’ sexual awakening and intellectual stimulation.

- Regis, Amber K. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

- Regis, Amber K. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

- Regis, Amber K. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

- The Society of Dilettanti. Specimens of antient sculpture, Ægyptian, Etruscan, Greek and Roman: selected from different collection in Great Britain. 1809.

- Ovid. Metamorphoses, in the Perseus Digital Library. http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:latinLit:phi0959.phi006.perseus-eng1:10.143-10.219

- Ovid. Metamorphoses, in the Perseus Digital Library. http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:latinLit:phi0959.phi006.perseus-eng1:10.143-10.219

- Symonds, J. Addington., Peters, R., Schueller, H. M. The letters of John Addington Symonds. Vol I. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. 1967.

- Symonds, J. Addington. Studies of the Greek Poets. Vol II. London : Smith, Elder. 1873.