If there is a theme that could perhaps define Symonds’ academic career, outside of Classic Greek literature, a case could certainly be made for his attachment and fascination toward Italy, something that can be gleaned by inference, looking at his catalog of work and his personal library. With one of the main pillars of the Renaissance taking place in Italy, Symonds’ love of classics would naturally lead him to Florence and Rome, and writers like Dante who took their cues from the writers of old. Much of Symonds’ body of work is concerned with not only the literature that came from the modern surroundings of Rome, but also the aesthetics and culture of the country. Symonds wrote multiple books such as Sketches in Italy and Greece that demonstrated an interest in the classical countries, beyond just tracing their literary history. Symonds also owned books such as those dealing with Italian architecture, and prominent Italian figures. Symonds also had personal reasons to be attached to Italy, between one of his friends owning a house where he often stayed in Venice, as well as his lover being a gondolier in the city of canals. Symonds’ personal connection to Italy, as a person and a scholar, is an undeniable part of his character.

Italian Byways is one of the books that catalogues the breadth of Symonds’ work, as it unites all of his interests in Italy in a way that fits someone with as unique a character as Symonds possessed. The book covers Italian architecture, but in a way that encompasses the historical context behind them, as well as Symonds’ scholarly background. While the book is ostensibly about some of the architecture in Florence and other parts of Italy, it is synthesized with Symonds’ own thoughts on art and the various legendary figures that inhabited those streets at other points in time. It showed he was a free thinking person in a time that could perhaps be called one of great conformity, if his sexual orientation and the frankness of his memoirs didn’t indicate that already, as well as how learned he was, showing off comparisons to classical architecture and drawing comparisons that displayed how much time and effort he had put into researching the architecture, as well as the history of certain classical adjacent authors.

But to me, by far the most interesting aspect of this book is Symonds’ own thoughts that he intersperses and elucidates throughout the book. He describes art (like architecture) as “in the business of creating an ideal world.” The tangible parts of art are “the mode of presentation through which spiritual content manifests itself.” As an English major myself, this resonated with me as it’s the very reason I was so interested in literature in the first place. All of those characters, stories, the beautiful representations of the potential of humanity, the acknowledgment of how far we could descend into depravity, that is what is so attractive about literature. It connects to something deep within us that recognizes our potential, for good or for ill, and puts it into a form digestible to us, analogous to Plato and the cave in which the captives can see shadows. As a person who could not be more different than Symonds in terms of background, it is a moment of respite to see how much we shared in this regard, of how we both saw how art required a certain connection to spirit to function. The human spirit is what invests art with meaning, what allows us to recognize why the form appeals to us so. That perhaps, is the most timeless thing that Symonds left us, the acknowledgment that art transcends time and touches upon humanity for a reason we all can understand, but not necessarily fathom.

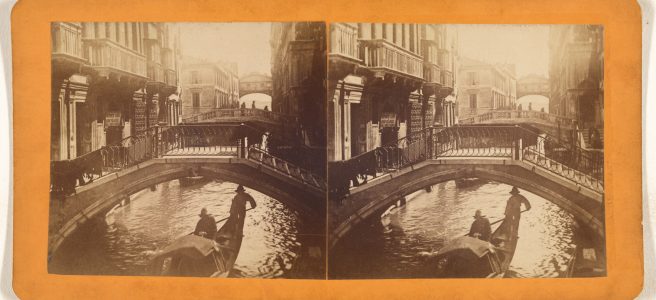

Featured image: Unknown maker, Italian, photographer [Canal, Venice, Italy], about 1865 Albumen silver print The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XC.873.8035. https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/107EM9