As a well-educated English literary man, John Addington Symonds had read the ancient Homeric epics in school by an early age, and it was from these stories that Symonds first learned ideas of Greek masculine love.

In Homer’s Iliad, military brotherhood is an intense bond. It is only when Patroclus dies that Achilles overcome his anger at Agamemnon and seeks vengeance, incited by love for his slain comrade. The true turning point of the epic lies in this epic love and change in passion: Hector, the slayer of Patroclus, must be slain by Achilles, the lover of Patroclus.

From fifth century BCE writers in antiquity to modern day scholars, the nature of the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus as presented by Homer has been a controversial matter for discussion: was it a relationship of homosexual love or heroic friendship?

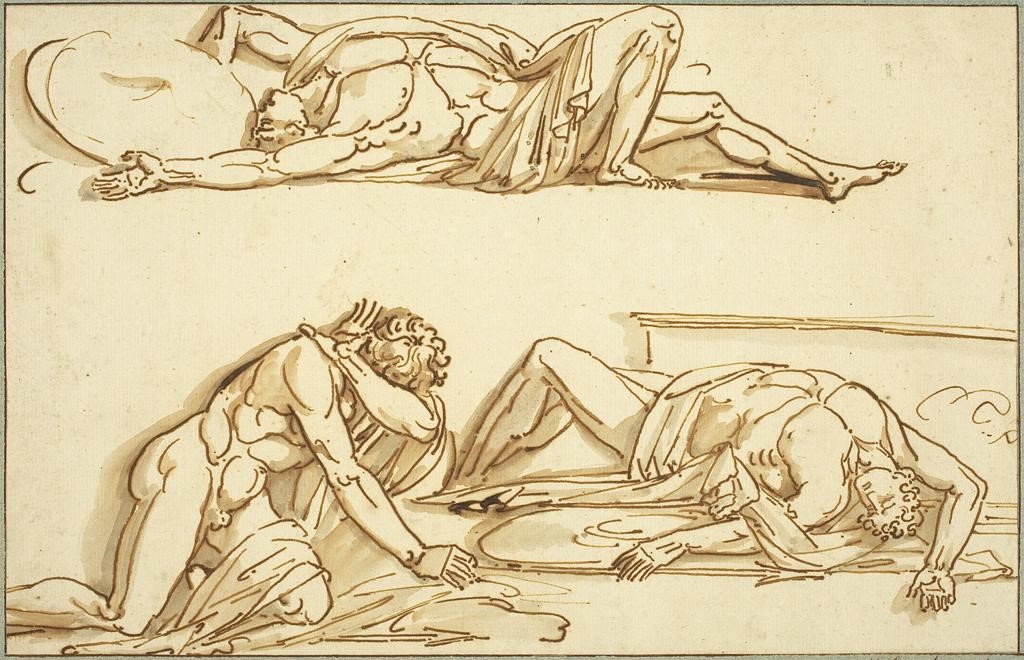

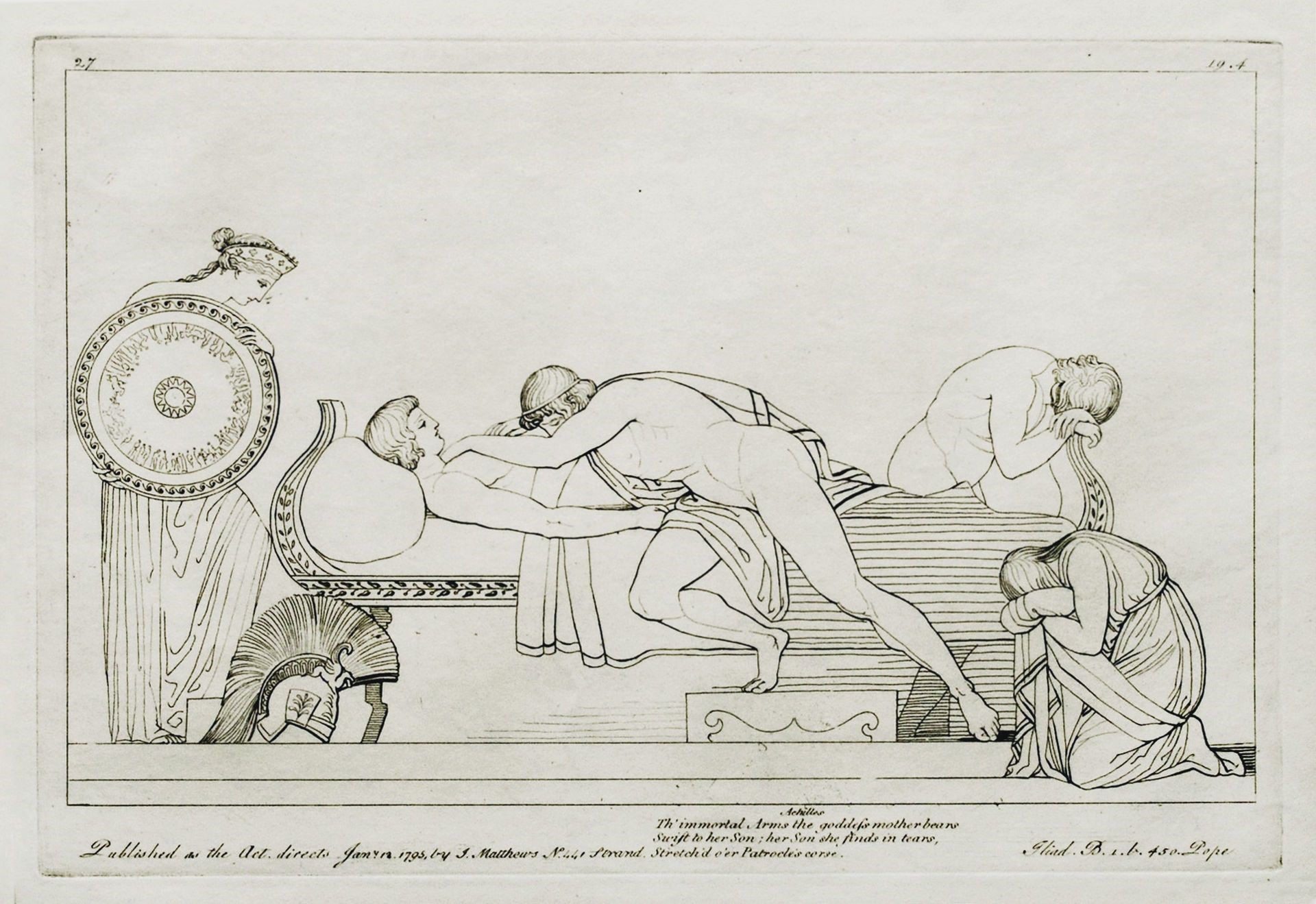

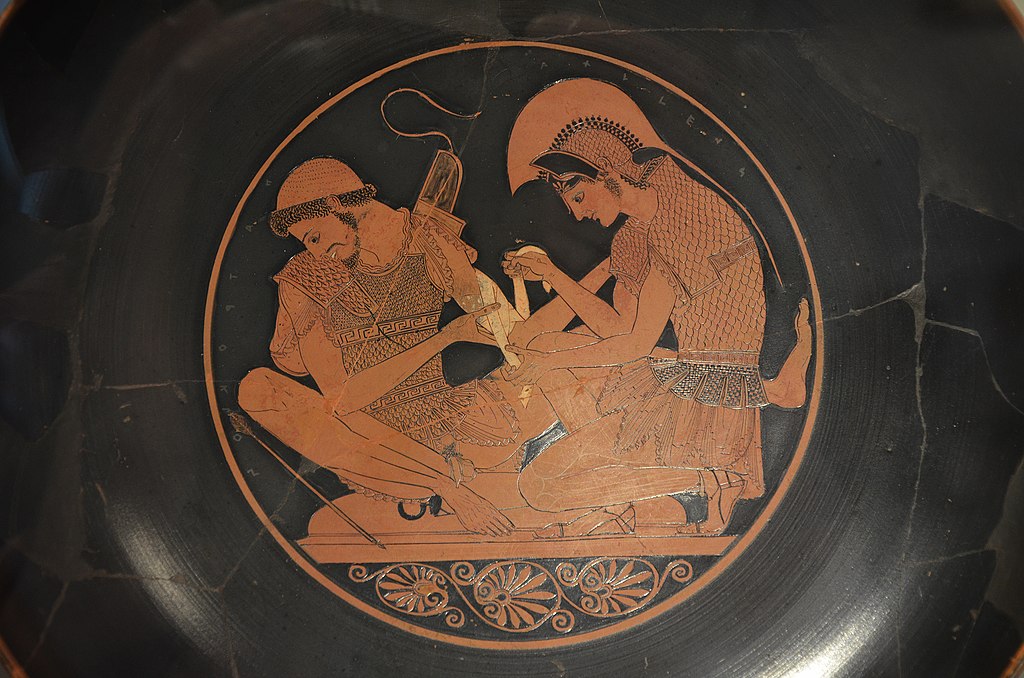

The long-term influence of the Iliad produced many illustrations of the tragic scene in modern-day reception. Throughout time, illustrations, including this kylix from Classical Greece, this sarcophagus from late antiquity, and this Hennequin drawing from modern times, are ambiguous on the exact nature of their relationship.

The image above is from a collection of illustrations based on scenes from Homer’s Iliad. This engraving by Tommaso Piroli, based on the original line drawings of John Flaxman, depicts Achilles lamenting the death of Patroclus. The image presents us with a scene of passionate mourning, with figures covering their faces and tensing their bodies, yet it does not imply anything homoerotic. This Flaxman drawing shows the ambiguity of this famous relationship: is it depicting a man lamenting the death of his best friend and comrade in war, or his romantic companion and sexual partner? The beauty in this engraving lies in the interpretation of its viewers – it can be whichever one chooses.

This book, published about 40 years before Symonds was born, could likely have been in his family’s library, something he would have seen as a child that would have shaped his understanding of ancient Greek literature. Since Homer became so essential to Symonds’ conception of ideal Greek male love, it is not hard to imagine him poring over visual depiction of the epic love story of Achilles and Patroclus. We can picture Symonds gazing at this drawing just as we are now, lamenting the untimely death of the Greek hero alongside Achilles and empathizing with the bitter emotions of those in the image. Perhaps Symonds would have even thought of his own male lovers, Willie Dyer and Alfred Brooke, and reminisced about the emotions he himself felt after losing those men.

Symonds references Homer often throughout his collected works, and many of the allusions concern the story of Achilles and Patroclus. In his essay A Problem in Greek Ethics, Symonds states that, at least in Homer, their companionship was not paiderastia – male love for a male youth – but simply heroic friendship (Greek Ethics 44). However, Symonds himself seems to doubt this definition of their relationship, considering that in later Greek history the love of Achilles for Patroclus became the canonical model and “almost religious sanction to the martial form of paiderastia” (Greek Ethics 44).

Later in his essay, Symonds contends that even ancient Greek students of Homer must have seen this friendship as an example for ideal masculine love. He describes their love as “a powerful and masculine emotion, in which effeminacy had no part, and which by no means excluded the ordinary sexual feelings…the tie was both more spiritual and more energetic than that which bound man to woman” (Greek Ethics 45). Even before the concept of paiderastia was established in Greek custom, the erotic often had a place in intimate male relations.

It seems very possible that Symonds held the same viewpoint, not as that of Homer, but as that of later Greeks, who read into the sentiments and passions of the text to find a romantic relationship between Achilles and Patroclus. Symonds cites Aeschines, in his Oration Against Timarchus, who discusses this question of Achilles’ love, saying “[Homer] indeed conceals their love, and does not give its proper name to the affection between them, judging that the extremity of their fondness would be intelligible to the well instructed men among his audience” (Aeschines 142).

Symonds would indeed fall under this “well-educated audience,” in which Achilles’ affection does not have to be overtly stated, as it is already implied. Fourth century BC Aeschines, like nineteenth century English scholars, could read Homer through the lens of homoeroticism, and Symonds himself shows real empathy to this idealistic Greek love in his own analysis.

Symonds read the Iliad along with other Greek classics in school and then went on to teach lectures on it. In an 1886 letter to Norman Moor, Symonds addressed the influence of homosexuality in classical literature in public schools. He believed that young boys “have been initiated into the mysteries of paiderastia unofficially long before their reading of the classics,” yet he thought that while they do read the Iliad in school, “it does not occur to them that there was anything between Achilles and Patroclus.” Here it seems that Symonds himself subscribed to the belief that there is a sexual and romantic component to the relationship of the two Greek heroes, but only if one is receptive and mature enough to perceive it. As he said in his Memoirs, it was not until age 18 when he read Plato that he encountered the catalyst for his own self-revelation of erotic male love, but once he acknowledged this in himself, he agreed that Patroclus and Achilles could be read as examples of Greek lovers.

Additionally, Aeschylus’ tragedy the Myrmidones, now lost, which would have been a popular sight in fifth century BCE Athens, portrays Achilles and Patroclus as lovers. Symonds was familiar with this story, in which Aeschylus presents Achilles as the erastes [lover], speaking to his dead beloved Patroclus, the eramenos [beloved]. In one fragment of the play, Achilles laments over the corpse of his friend, his lower limbs uncovered – the same scene depicted more modestly on Flaxman’s engraving above – with unmeasured passion that describes the intimate love between the two heroes. Here Achilles mournfully reproaches that, in his forbidden advance against the Trojans, Patroclus had been heedless of his dear affection:

“For the pureness of the thighs, you have no reverence, O most ungrateful for my frequent kisses!” (Athenaeus, Deipnosophists xiii.79 13.602e frag. 64)

As the Iliad is a work of fiction, the question of a possible homosexual relationship here is not one of historical accuracy. In Piroli’s engraving, as well as in many late Greek stories and illustrations from antiquity to modern-day, it seems that Achilles and Patroclus did have an intimate relationship as lovers. But it does not really matter to us whether this would have been possible in Homeric society. Instead of pondering over hypotheticals, we can find in the Iliad a familiar love story told in romantic discourse. For us, and for Symonds, we can relate to their timeless relationship, and the possibility of seeing queer love in such an ancient story.

At least for Symonds, it is likely a depiction of historically bounded ideal Greek love, the idealist homosexual affection he himself had experienced and dedicated his life to studying. Yet it does not matter whether or not Homer really intended to portray the relationship of Achilles and Patroclus as ‘heroic friendship’ or that of lovers, for from 4th c. BC Greece onward, their relationship has become the canonical representation of Greek male love.

Works Cited:

Featured image: Philippe-Auguste Hennequin, “Achilles and Patroclus,” 1784. Pen and brown ink with brown-grey wash on laid paper. Sheet: 20.5 x 30.9 cm. The National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C), Joseph F. McCrindle Collection Inv. No. 2009.70.141, via Artstor.

Johns Addington Symonds (1840-1893) and Homosexuality. “Chapter 2: A Problem in Greek Ethics.” Palgrave Macmillan Publishing. Basingstoke, 2012. Print.

The Letters of Johns Addington Symonds. Wayne State University Press. Detroit, 1967. Print.

Symonds, John Addington. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition. Palgrave Macmillan Publishing. London, 2016. Print.