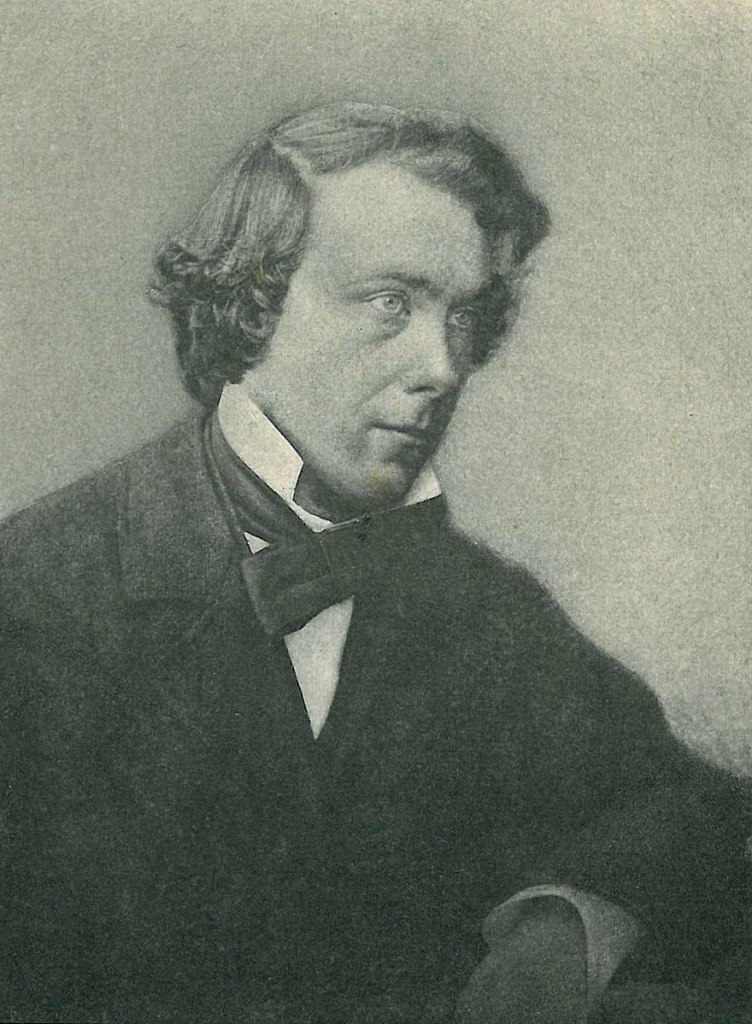

“L’Amour de L’Impossible.”

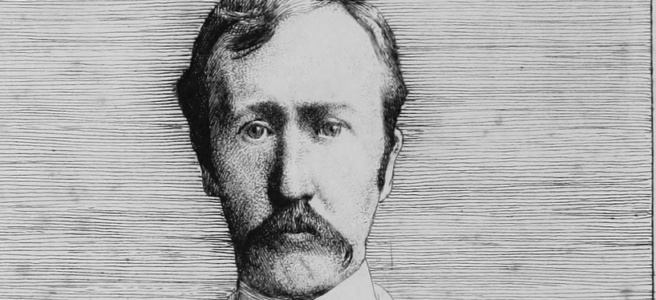

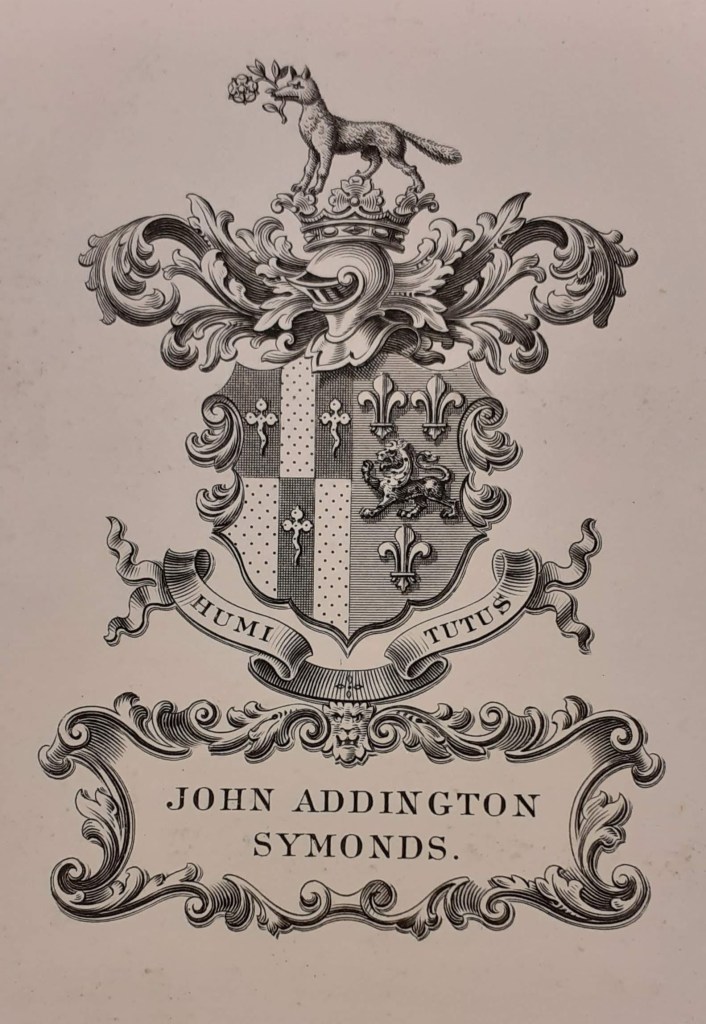

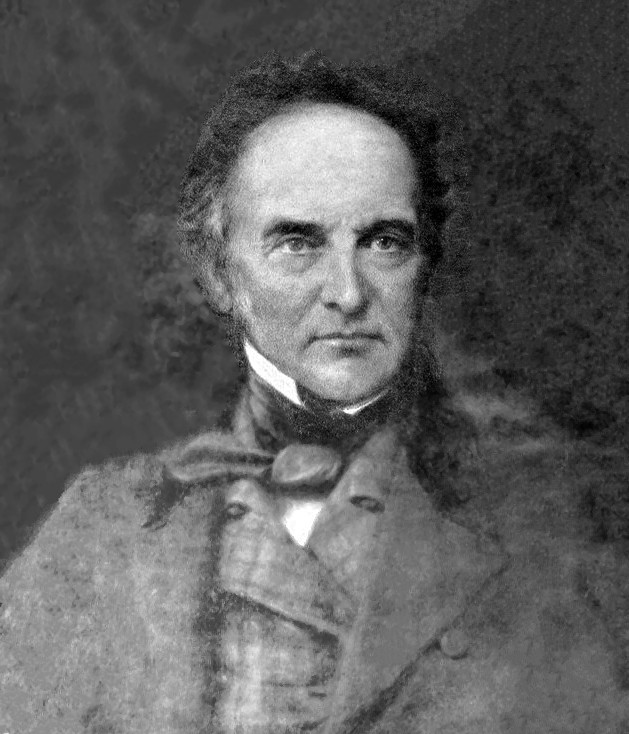

This phrase, translated as “the love of the impossible,” has stuck in my mind. It’s a frequent flier in John Addington Symonds’s diction, especially throughout his Memoirs,but I can’t help but pause— even for a moment—whenever I encounter it. There’s a dance that plays out whenever the phrase steps onto the page: l’amour, or “the love,” on one side, and l’impossible, or “the impossible,” on the other. These two parts are not polar opposites,but when put together, they create tension. Love, a fluid, dynamic concept that I associate with passion and flame, mixes strangely with impossible, that icy, uncaring boundary.

The grammar of the phrase emphasizes this tension as well. “The love of the impossible” subordinates “impossible” to “love,” but the phrase also uses the adjective “impossible” as a noun and pairs it with the article “the,” creating visual parallels between it and “the love.” This verbal visual appears much the same in French: the adjective “impossible” becomes the noun-like l’impossible and grabs an article for itself, allowing it to dance in visual (but not grammatical) apposition with its partner, l’amour.

Of course, I don’t believe that Symonds’s connection to l’amour de l’impossible ends at a mere grammar lesson. First, I think we can better understand why the tension of l’amour de l’impossible matters to Symonds by contrasting it with the similar-sounding l’amour impossible, or “impossible love.” Consider the following quote from Chapter 3 of Shane Butler’s The Passions of John Addington Symonds regarding the contents of Symonds’s love poem, “The Passing Stranger”:

“The whole stretch of time, in other words, becomes for Symonds the canvas of what he famously, and repeatedly, calls l’amour de l’impossible, “love of the impossible,” which is not, though the subtlety is often missed, itself an impossible love” (Butler 122).

“The love of the impossible” is, by definition, possible, unlike an “impossible love.” However, the possibility suggested by “the love of the impossible” inevitably clashes with the impossibility that is also suggested by the phrase. Symonds, attempting to understand his own sexuality in the 19th century, grappled with this very tension between the possible and the impossible. His Memoirs tell us that he knew very well that he loved the men he fell in love with in his personal life, but he struggled throughout his public life to find a place in his world for sexual and romantic love between men. The love he feels is well-past possible, but the queerness inherent to this love goes hand-in-hand with his seemingly-impossible task of fitting a queer mode of love into 19th century English thought.

Ultimately, I think that Symonds’s connection to l’amour de l’impossible is exemplified by his work of the same name, “L’Amour de L’Impossible.” The work, a series of fourteen poems, is an extended meditation on love and the mind, and I argue that it is a semi-autobiographical work that encapsulates the tension inherent to “the love of the impossible.”

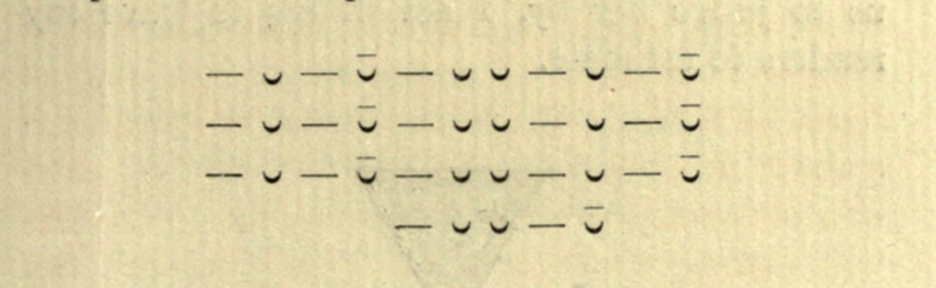

“L’Amour de L’Impossible” evokes the two-sided tension between “the love” and “the impossible.” through its overarching structure. Although the poem is ostensibly divided into fourteen parts, these parts can be divided by their contents into two larger sections, six parts each, with an interlude consisting of two parts in the middle. The first half calls forth the sparks of passion and fantasy that accompany the “possible,” while the second half evokes the feelings of anguish and wanting that come from a struggle with the “impossible.”

“Three times the Muse, with black bat wings outspread,

Darkening the night, with lightning in her eyes

And wrath upon her forehead, bade me rise

Where I lay slumbering in oblivion’s bed.

The first time I was young; and though I had shed

Hot tears for fear of that great enterprise,

I followed her, forth to the starless skies,

and sang her songs, wild songs of pain and dread.

The second time I listened and obeyed:

Presumptuous! for that same thick cloud of song

Dwelt on my manhood with a dreadful shade.

Once more she comes and calls me all night long.

Nay, Muse of Death and Hades! We have played

O’ermuch with madness! Ah, thou art too strong!” (“L’Amour de L’Impossible,” “Prooemium“)

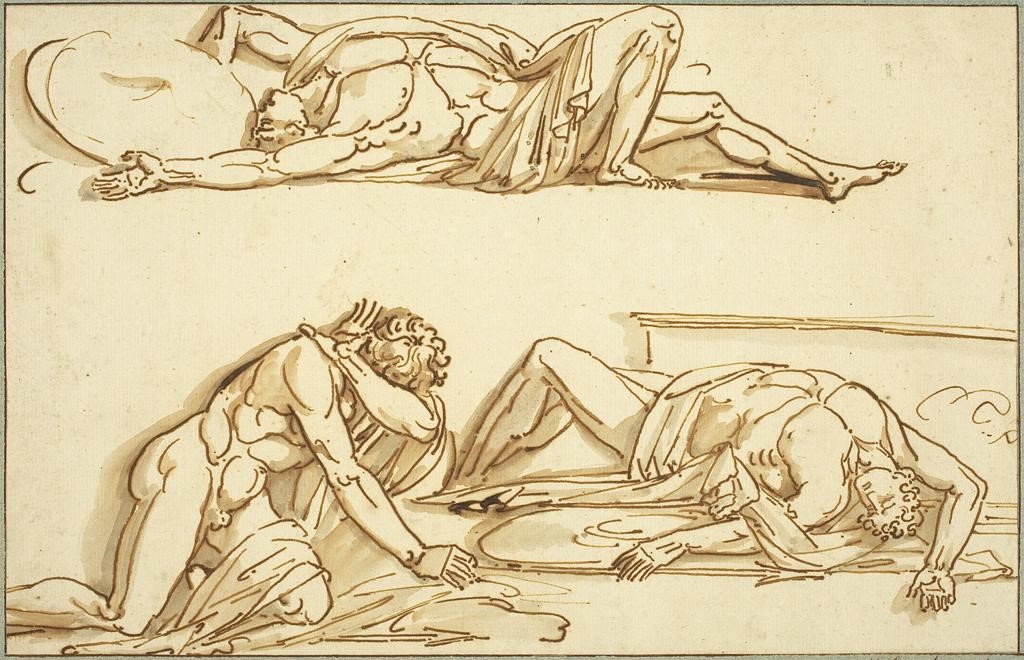

Part I (“Prooemium“) invokes a Muse, who introduces the speaker with a “great enteprise” which he will first sing uncertainly, then later with strength to the point of madness. Connecting this Muse to Symonds’s life, Symonds tells us in Chapter 2 of his Memoirs that one of his earliest memories of sexuality was a waking dream in which he “crouched upon the floor amid a company of naked adult men,” a dream which he believes was “so often repeated, so habitual, that there is no doubt about its psychical importance (Memoirs 100). This dream, which Symonds uses in his Memoirs to remove agency from his younger self regarding the development of his sexuality, mirrors the divine Muse which drives the speaker to sing the songs which would later “dwell on [his] manhood with a dreadful shade.” Symonds informs us throughout the following chapters of his Memoirs of his draining, life-long struggle living as a homosexual man in a society that is hostile to his sexuality, a conflict that he considered an “inexorable and incurable disease,” and his efforts to confront said struggle through his work in sexuality. Thus, the Muse of the “Prooemium” (“beginning,” or “prelude,” in Latin) reflects both the passivity which Symonds associates with his personal introduction to sexuality and the impossible struggle of reconciling his sexuality with the society in which he lived. Importantly, the “Prooemium” also reflects Symonds’s efforts to take on the challenge of said struggle.

“Chimaera, the winged wish that carries men

Forth to the bourne of things impossible

Maya, the sorceress, who meets them when

Their hearts with vague untameable longing

swell;

These wait on wrinkled Madness, in her den

Crouching with writhen smile and mumbled spell.

Dread sisters! Though thou hadst the strength of ten,

Down shalt thou go into the depths of hell,

Should one of those once make thy spirit her prize.

Who love what may not be, are sick of soul;

And sick of soul who seek with thirsting eyes

Wells where the desert’s mirage mist-wreaths roll.

Who wed discretion, they alone are wise;

And who place limits on their lusts, are whole.” (“L’Amour,” “The Furies”)

“ἐρᾶν ἀδυνάτων νόσος τῆς ψυχῆς

Childhood brings flowers to pluck, and butterflies;

Boyhood hath bat and ball, shy dubious dreams,

Foreshadowed love, friendship, prophetic gleams;

Youth takes free pastime under laughing skies;

Ripe manhood weds, made early strong and wise;

Clasping the real, scorning what only seems,

He tracks love’s fountain to its furthest streams,

Kneels by the cradle where his firstborn lies.

Then for the soul athirst, life’s circle run,

Yet nought accomplished and the world unknown,

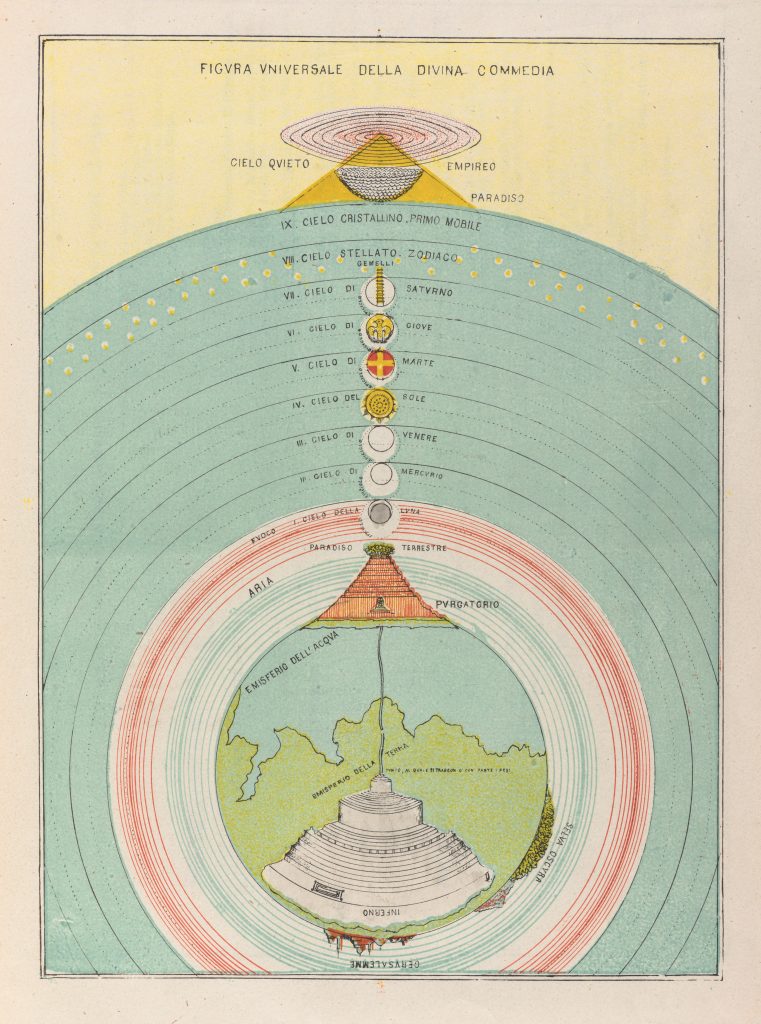

Rises Chimaera. Far beyond the sun

Her bat’s wings bear us. The empyreal zone

Shrinks into void. We pant. Thought, sense rebel,

And swoon desiring things impossible.” (“L’Amour,” “Chimaera“)

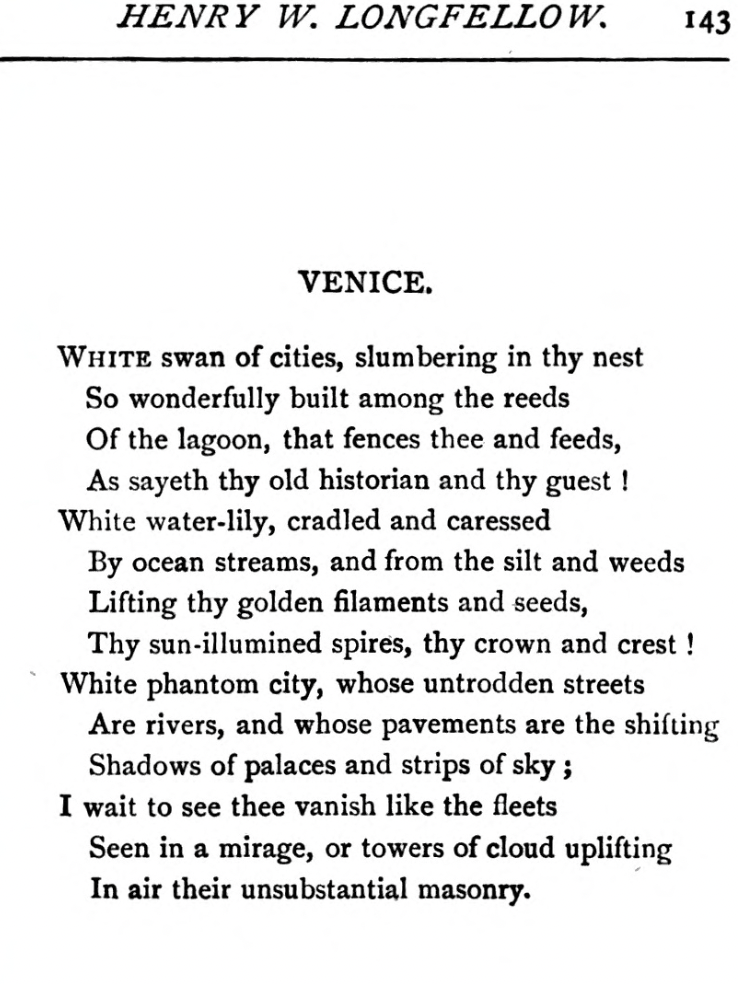

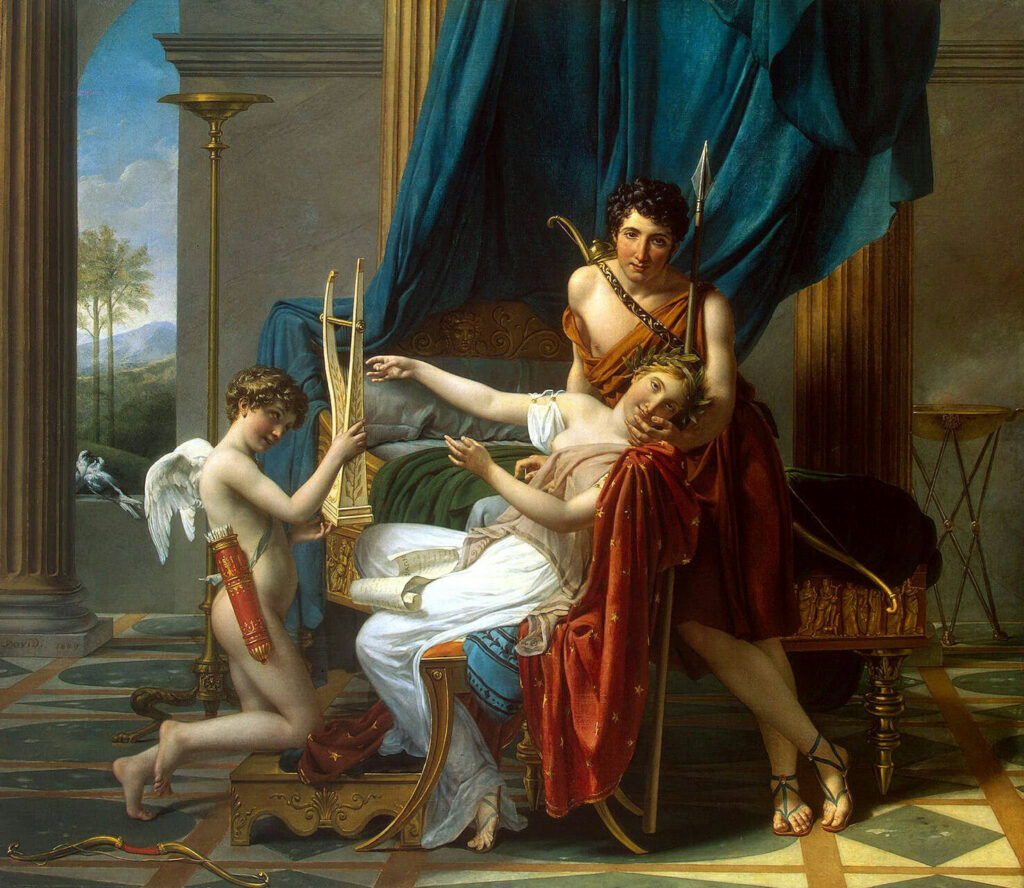

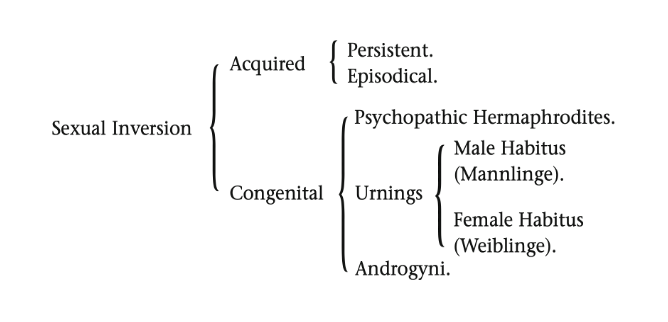

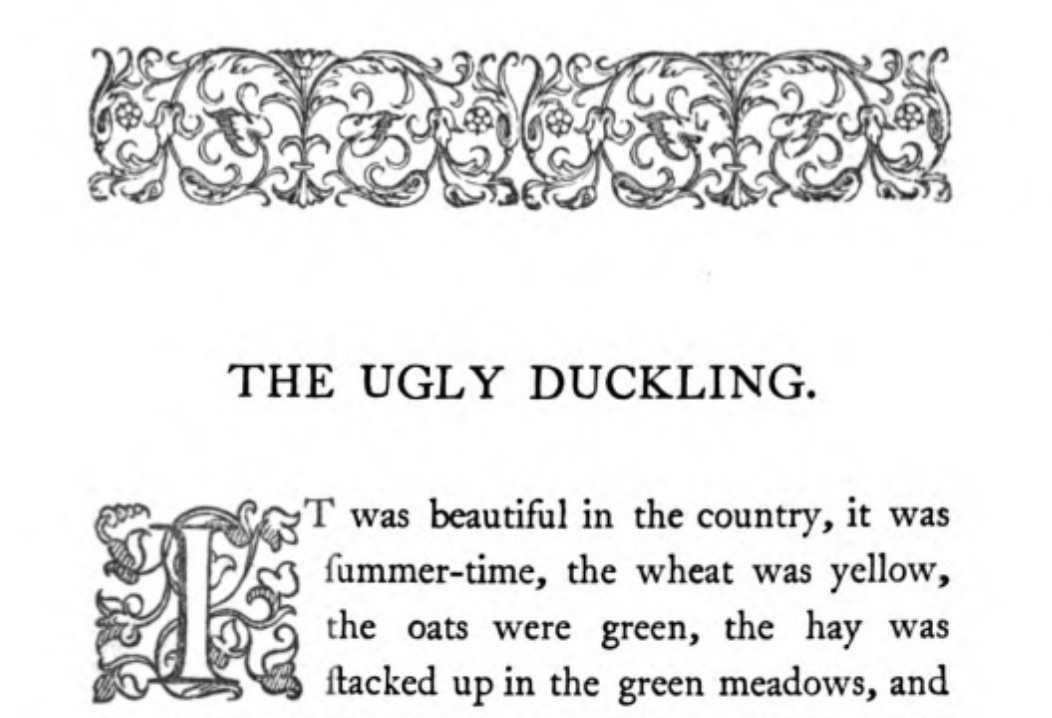

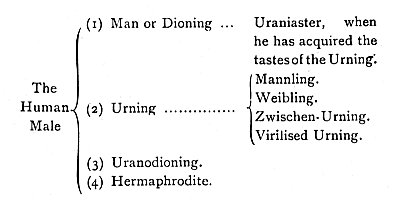

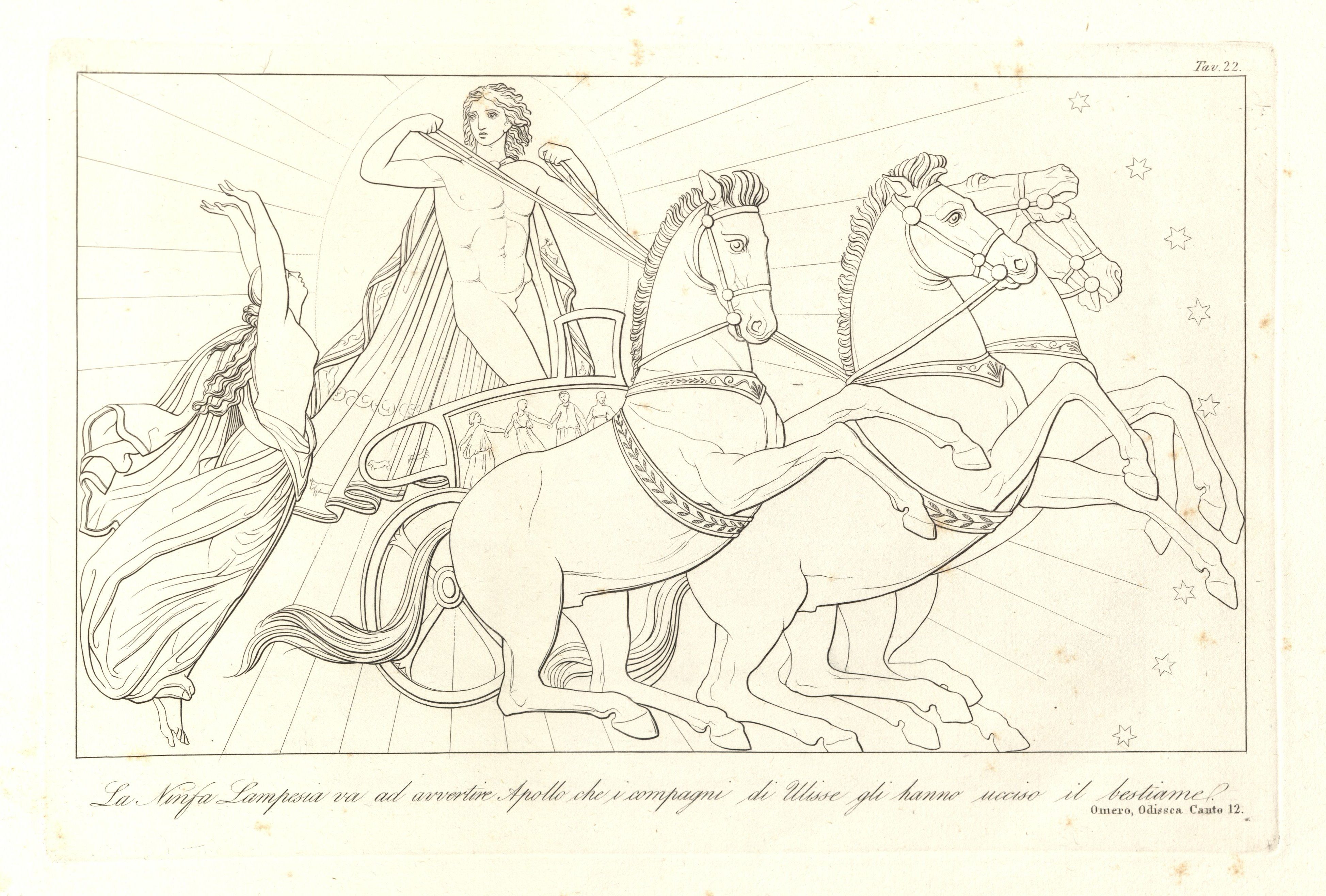

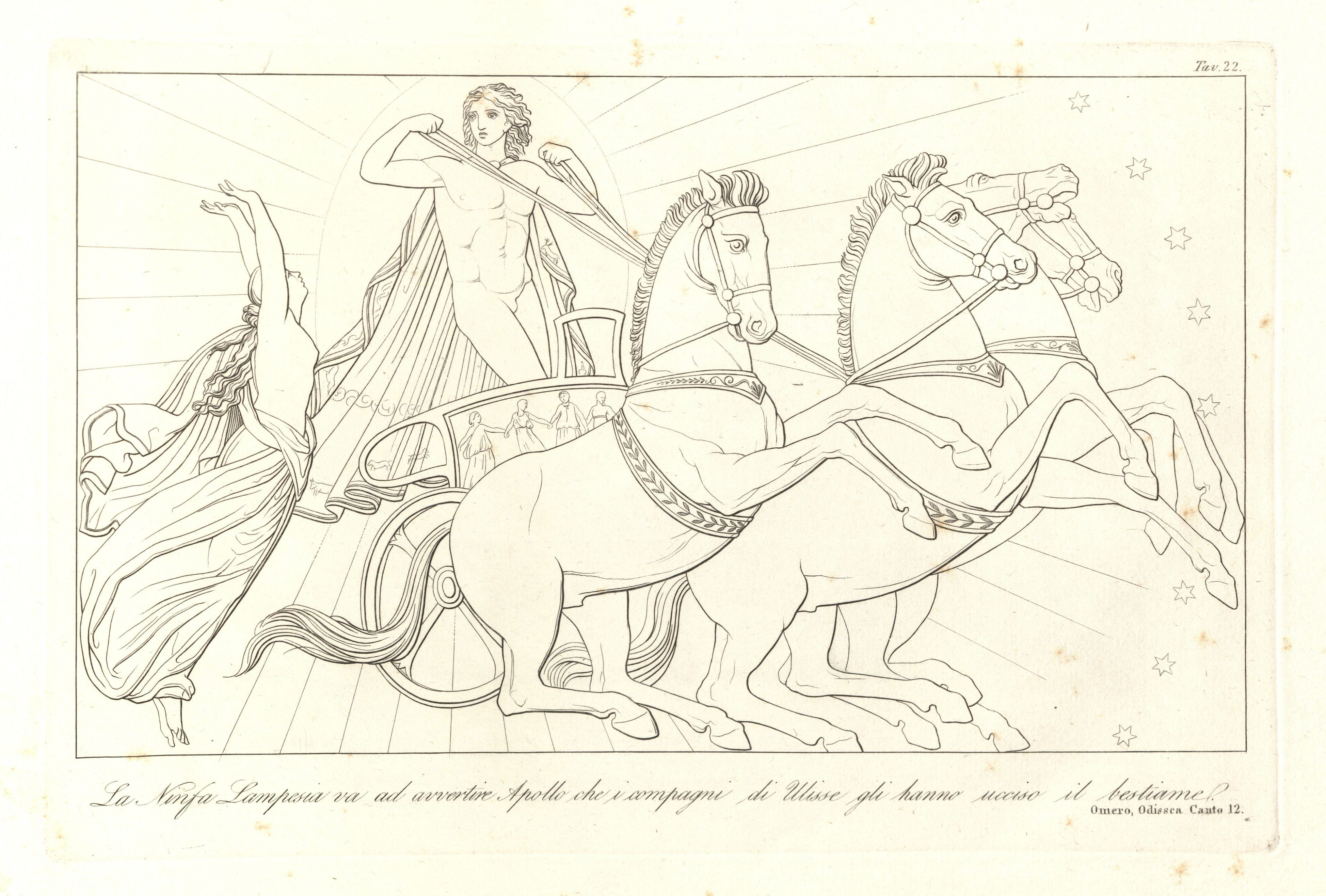

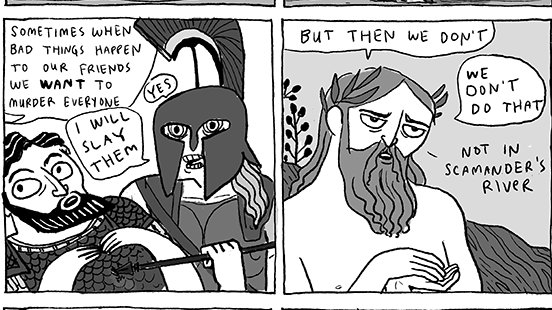

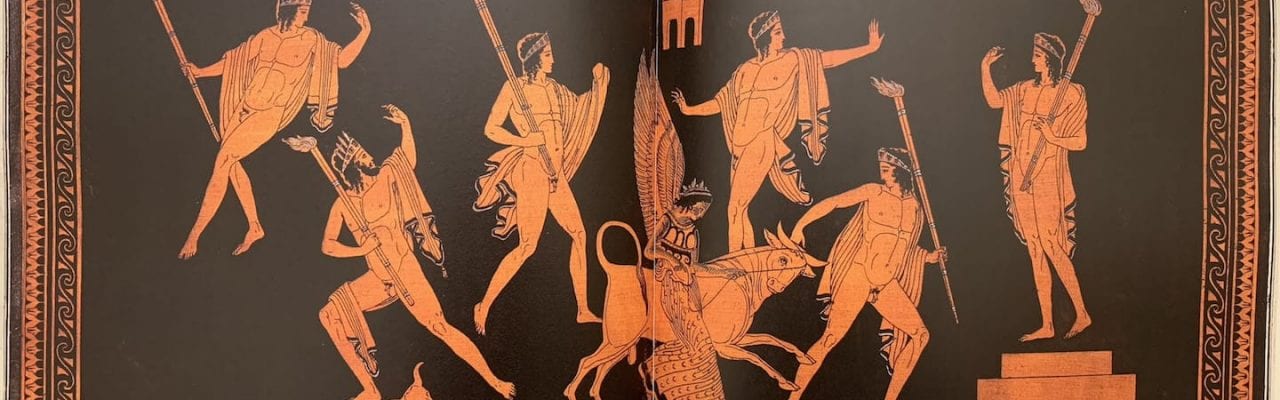

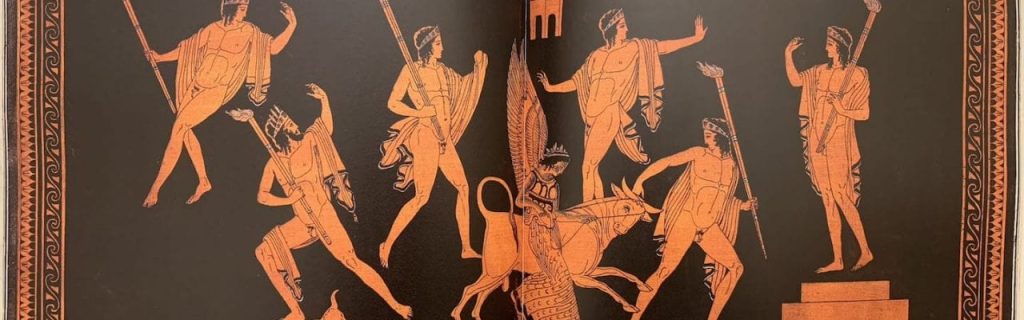

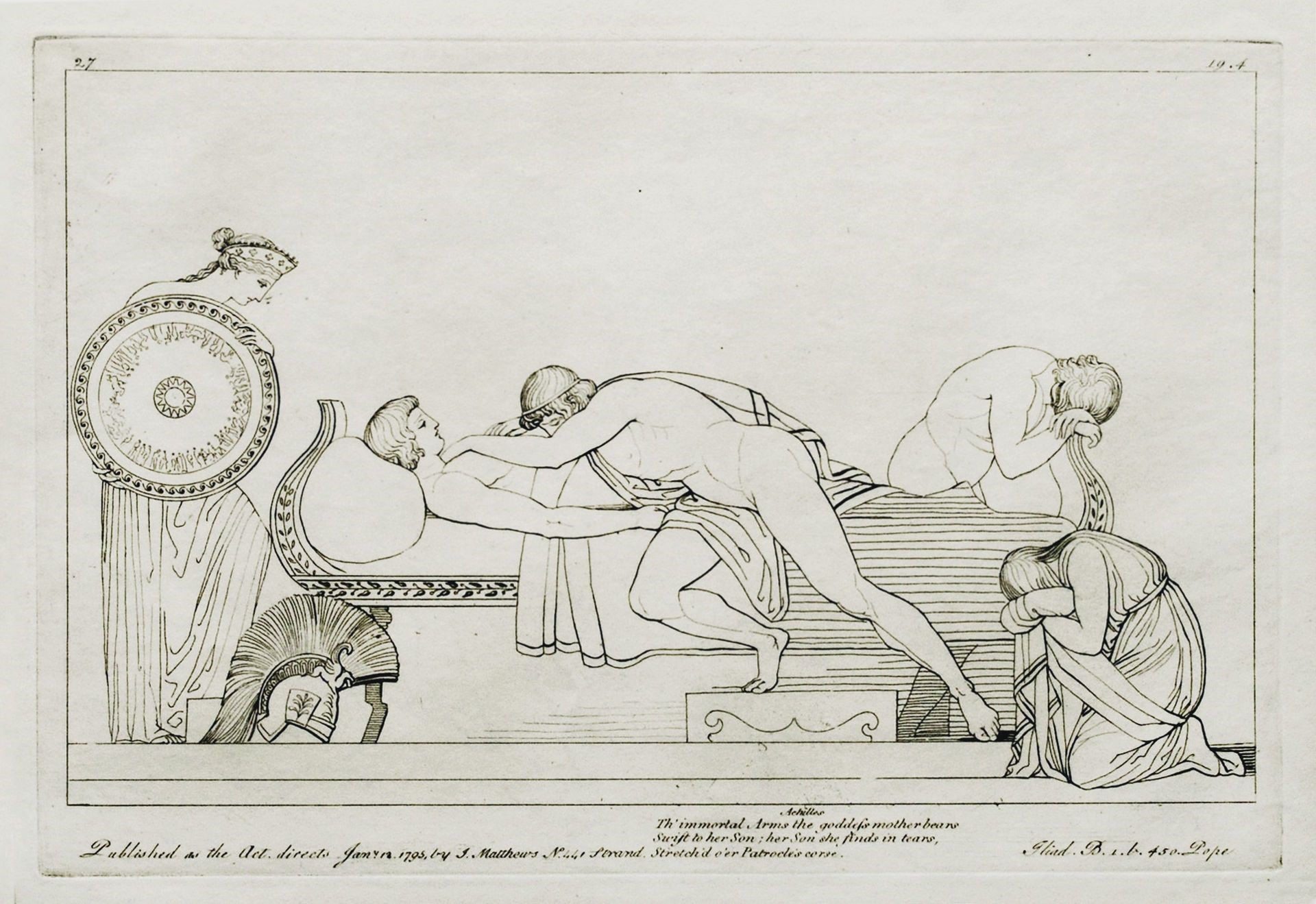

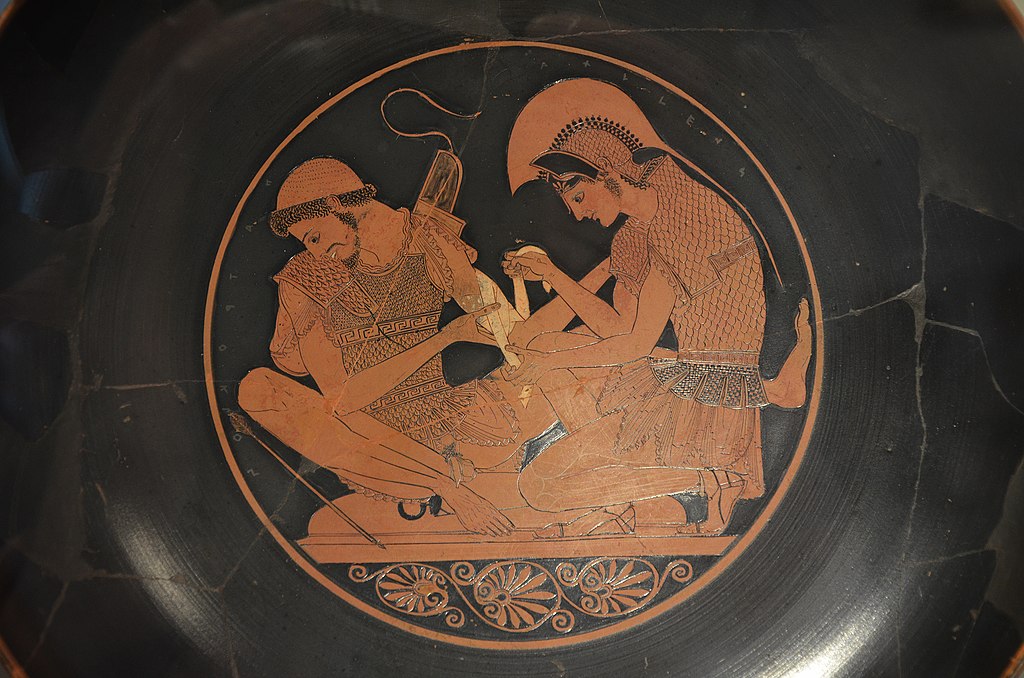

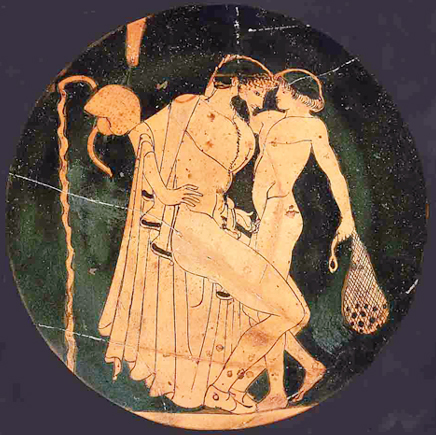

Parts II (“The Furies”) and III (“Chimaera“) introduce the Chimaera (or “Chimera”), a figure which represents the love of the impossible. On one hand, the Chimaera of Greek mythology is a fantastic monster formed from the parts of various creatures. On the other hand, “chimera” also comes to mean “wild fancy” in English by the 16th century (Oxford English Dictionary). Thus, the Chimaera becomes the process of mind which offers that wild fancy, or as Butler puts it, a “chimerical erethism” (Butler 179), to those who become “sick of soul” and “soul athirst” from being starved of love. The “sickness” which the Chimaera alleviates calls to mind Symonds’s language regarding the dissonance between his sexuality and the society of 19th century England: an “inexorable and incurable disease” which he has dedicated his life’s work to. To expand on this connection, Symonds uses the exact phrase “ἐρᾶν ἀδυνάτων νόσος τῆς ψυχῆς” (“loving of the impossible (is) the disease of the soul” in Ancient Greek) to discuss the “love of the impossible” in both “L’Amour de L’Impossible”and in his Memoirs. Further, as Butler notes, this Greek phrase is in fact the “original” phrase, of which the French phrase is a translation: “The title phrase translates the first part of a pronouncement by the ancient Greek philosopher Bias of Priene that seems to have become proverbial” (Butler 177). The society which Symonds lives in rejects homosexuality, excluding him from the possibility of being able to engage in love freely. As Butler describes, such a free love is “a possibility [Symonds] depressingly admits for heterosexual love alone” (Butler 178). Thus, Symonds loves what is impossible in his society: free love between equal men.

“Man’s soul is drawn by beauty, even as the moth

By flame, the cloud by mountains, or as the sea,

Roaming around earth’s shore incessantly,

Ebbs with the moon and surges with her growth;

And as the moth singes her wings in fire,

As clouds upon the hillsides melt in rain,

As tides with change unceasing wax and wane,

Nor in the moon’s white kisses quell desire;

So the soul, drawn by beauty, nothing loth,

Burns her bright wings with rapture that is pain,

Faints and dissolves or e’er her goal she gain,

Flies and pursues that unclasped deity,

Fretful, forestalled, blown into foam and froth,

Following and foiled, even as I follow Thee! (“L’Amour,” “The Pursuit of Beauty”)

“There are who, when the bat on wing transverse,

Skims the swart surface of some neighbouring mere,

Catch that thin cry too fine for common ear;

Thus the last joy-note of the universe

Is borne to those few listeners who immerse

Their intellectual hearing in no clear

Paean, but pierce it with the thin-edged spear

Of utmost beauty which contains a curse.

Dead on their sense fall marches hymeneal,

Triumphal odes, hymns, symphonies sonorous;

They crave one shrill vibration, tense, ideal,

Transcending and surpassing the world’s chorus;

Keen fine, ethereal, exquisitely real,

Intangible as star’s light quivering o’er us. (“L’Amour,” “The Vanishing Point”)

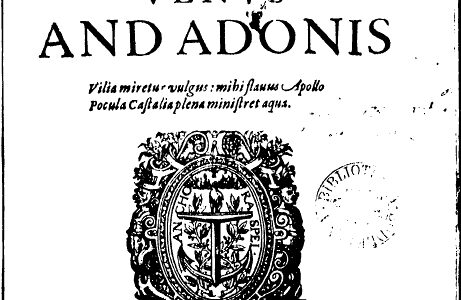

Parts IV (“The Pursuit of Beauty”) and V (“The Vanishing Point”) engage heavily in the role of beauty as an inescapable force of attraction for humans. The speaker compares humanity’s attraction to beauty to a moth drawn to flame. Furthering the analogy, the speaker believes that this attraction to beauty is cursed, leading inevitably to pain, just as the moth “singes her wings in fire.” Applying Part IV’s attraction to beauty to a sexual/romantic attraction to people, Symonds refers many times to his early exposures to sexuality using the word “beauty”: Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis “gave form, ideality and beauty to my previous erotic visions” (Memoirs 101), Symonds describes the crux of the “anomaly” of his sexuality as being his “[admiration for] the physical beauty of men over women” (Memoirs 103), and he describes a recurring childhood dream he had of a young man as a “vision of ideal beauty under the form of a male genius” which “symbolized spotaneous yearnings deeply seated in my nature” (Memoirs 117-118). The “utmost beauty” which Symonds attributes his sexual/romantic love of men to would inevitably come into conflict with his society’s rejection of his sexuality: the “curse” which he would struggle with for the rest of his life.

“Seraph, Medusa, Mystery, Sphinx! Oh Thou

That art the unattainable! Thou dream

Incarnate! Thou frail iridescent gleam!

Fugitive bloom atremble on life’s bough!

Fade, prithee, fade; and veil thy luminous brow,

Chimaera! Let me ruin adown the stream

Of the world’s desolation! All things seem,

Mock, change, illude, from time’s first pulse till now.

Nothing is real but thirst, the incurable,

Thirst slaked by nought save god withdrawn from sight;

And God is life’s negation; with Him dwell

Souls swallowed in the ocean of blank night,

Where vast Nirvana drowneth heaven and hell,

And self-annihilation is delight.” (“L’Amour,” “The Tyranny of Chimaera“)

Part VI (“The Tyranny of Chimaera“) depicts the speaker turning against the Chimaera, begging it to release him from his longing for the impossible, an unquenchable thirst. The Chimaera, which can only offer transient dreams, has become a burden to the speaker. We can understand from the Memoirs that Symonds’s love of the impossible has become his own personal burden: the “incurable” disease, to repeat language from the Memoirs which also reappears in “The Tyranny of the Chimaera.” Living in a society where he cannot express love freely, Symonds’s Memoirs tell us that he consideredhis sexuality to be the “poison of his life.”

“Learn to renounce! Oh, heart of mine, this long

Life-struggle with thyself hath been for thee

Nought but renunciation! Souls are free,

We cry in youth, and wish can work no wrong.

Thus planted I the fiend of fancy strong

Within the palace of my mind, to be

Master and lord, for perpetuity

Of anguish, o’oer a fierce rebellious throng:

Those tyrannous appetites, those unquelled desires,

Day-dreams arrayed like angels, longing crude,

Forth-stretchings of the heart toward wandering fires,

Forceful imaginations, love imbued

With hell and heaven commingling, which have thrust

Hope, health, strength, reason, manhood in the dust. (“L’Amour,” “Renunciation”)

“He that hath once in heart and soul and sense

Harboured the secret heat of love that yearns

With incomunicable violence,

Still, though his love be dead and buried, burns:

Yea, if he feed not that remorseless flame

With fuel of strong though for ever fresh,

The slow fire shrouded in a veil of shame

Corrodes his very substance, marrow and flesh.

Therefore, in time take heed. Of misery

Make wings for soaring o’er the source of pain.

Compel thy spirit’s strife to strengthen thee:

And seek the stars upon that hurricane

Of passionate anguish, which beyond control

Pent in thy breast, would rack and rend thy soul. (“L’Amour,” “The Use of Pain”)

Parts VII (“Renunciation”) and VIII (“The Use of Pain”) portray burning passion as a ruinous hunger, which slowly poisons a man if not fed. Symonds, describing his struggles with the “poison of [his] life,” details how he would tend to his own “remorseless flame” in different ways, ranging from writing poetry to reading literature and observing bathers in the public baths (Memoirs 367-370). Ultimately, these methods could not make up for the fact that Symonds’s society did not permit him to freely engage with his sexuality: Symonds notes how he ended a period of his private compositions because they “kept [him] in a continual state of orexis [“appetite,” in Ancient Greek], or irritable longing” (Memoirs 367; 375).

Parts IX (“Limbo”) and X (“Wishes”) describe the pain of longing for something that has been denied, which humans want for even in death. Along the Lethe, the river where the dead go to wash away their memories, a crowd of souls, unable to move on, cries out: “We lived not, for we loved not! Dreams are we!” Symonds expresses that he believes that he “shall die without realizing what constitutes the highest happiness of mortals, an ardent love reciprocated with ardour. This I could never enjoy, for the simple reason that I have never felt the sexual attraction of women” (Memoirs 369). Symonds, as a homosexual man, longs for the ability to freely love other men, but that ability lies within the realm of the impossible, as the society he lives in denies him such freedom.

“The gaunt grey belfrey spake. Those crazy bells

Sent to my soul three divers messages.

The Bass said: Eat, drink, slumber; take thine ease;

Nothing abides; void are heaven’s promised wells!

The Tenor sang: Life flies; my music tells

Of human bliss; delay not, seek and seize!

Then, bat-like, shrill, borne on the twilight creeze

The Treble cried: Buy, buy what fancy sells!

Yet each voice taught me nothing. How shall I

Glut me on thy gross naquet, booming Bass?

And Tenor, youth was kind, but I was shy!

And thou, keen Treble, is the nightly chase

Of dreams that sting but do not satisfy,

Food for the soul that craves some living grace? (“L’Amour,” “Convent Bells”)

“Morning of life! O ne’er recaptured hour,

Which some have dulled with fumes of meat and wine;

And some have starved upon the bitter brine

Of lean ambition grasping place and power;

And some have drowned in Danae’s vulgar shower

Caught by keen harlot souls where ingots shine;

And some have drowsed with ivy wreaths that twine

Around Parnassus and the Muse’s bower;

And some exchanged for learning, pelf of thought;

And some consumed in kilns of passions hot

With lime and fire to sear the sentient life;

And some have bartered for high-blooded strife

Of battle;—where art thou? These have all bought

With thee their heart’s wise. Youth! I sold thee not.” (“L’Amour,” “Dove sono i bei Momenti“)

Parts XI (“Convent Bells”) and XII (“Dove sono i bei Momenti“) center around youth and how people struggle to spend it well. The speaker tells the talking bells, which act as inner dialogue for the speaker, that seizing the day and rejoicing in little victories can only do so much to satisfy a person’s life, and he describes different ways in which people spend their youth for the sake of said satisfaction, only to burn out. In turn, Symonds offers the following in his Memoirs: “Then again what hours and days and weeks and months of weariness I have endured by the alternate indulgence and repression of my craving imagination. What time and energy I have wasted on expressing it. How it has interfered with the pursuit of study. How marriage has been spoiled by it” (Memoirs 369). The Memoirs tell us that he has never been able to satisfy his soul’s yearnings, only being able to waver along a thin line between “indulgence” and “repression” for his imagination. The impossible which he loves weighs heavily on him, but he presses on, even so far past his younger days.

“God and the saints forgive us—we who blight

With mists of passion and with murk of lust

This wonderful fair world, and turn to dust

The diamonds of life’s innocent delight!

Who bear within our hearts black envious night,

Blunting the blade of joy with sensual rust,

Breaking vain wings against the stern Thou Must

Blazed in star-fire on Nature’s brows of light!—

Nature, thou gentle mistress, back to thee

Thy wandering children bring their cureless thirst!

Take them, and nurse them, mother, on thy knee!

Teach them, with vain insatiate longing cursed,

To cool life’s ardent anguish at thy breast;

And thy law that limits give them rest! (“L’Amour,” “Natura Consolatrix“)

“Sleep, that art named eternal! Is there then

No chance of waking in thy noiseless realm?

Come there no fretful dreams to overwhelm

The feverish spirits of o’erlaboured men?

Shall conscience sleep where thou art; and shall pain

Lie folded with tired arms around her head;

And memory be stretched upon a bed

Of ease, whence she shall never rise again?

O sleep, that art eternal! Say, shall love

Breathe like an infant slumbering at thy breast?

Shall hope there cease to throb; and shall the smart

Of impossible things at length find rest?

Thou answerest not. The poppy-heads above

The calm brows sleep. How cold, how still thou art!” (“L’Amour,” “To the Genius of Eternal Slumber”)

Parts XIII (“Natura Consolatrix“) and XIV (“To the Genius of Eternal Slumber”) personify nature and sleep, two forces beyond the control of humankind, in the futile hope of finding repose from longing and want. Symonds also personifies Nature in the Memoirs: “Nature is a hard and cruel stepmother. Nothing that I could have done would have availed to alter my disposition by a hair’s breadth” (Memoirs 369). The Memoirs imply that the “Consolatrix” (“comforter,” in Latin) in “Natura Consolatrix” (“Nature, the comforter,” in Latin) is ironic. Nature, which does not care for the mores of human society, is cold comfort for the wanting souls it creates, and eternal sleep offers nothing but eternal sleep. It is up to Symonds’s own strength to wrestle with the impossible which he loves.

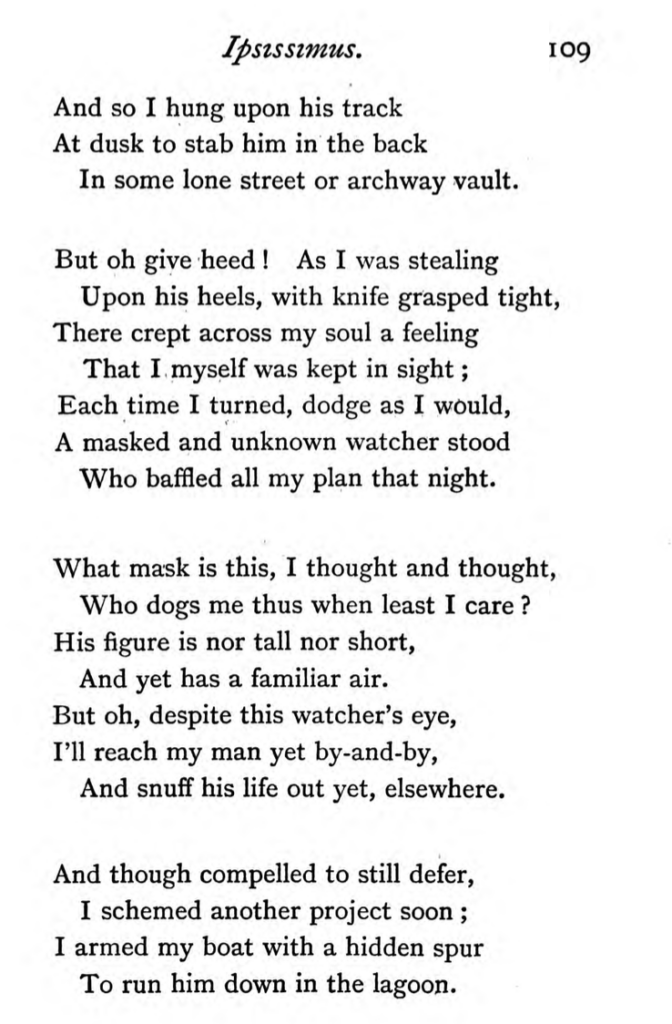

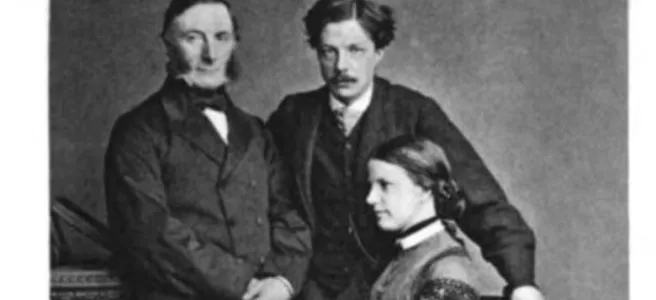

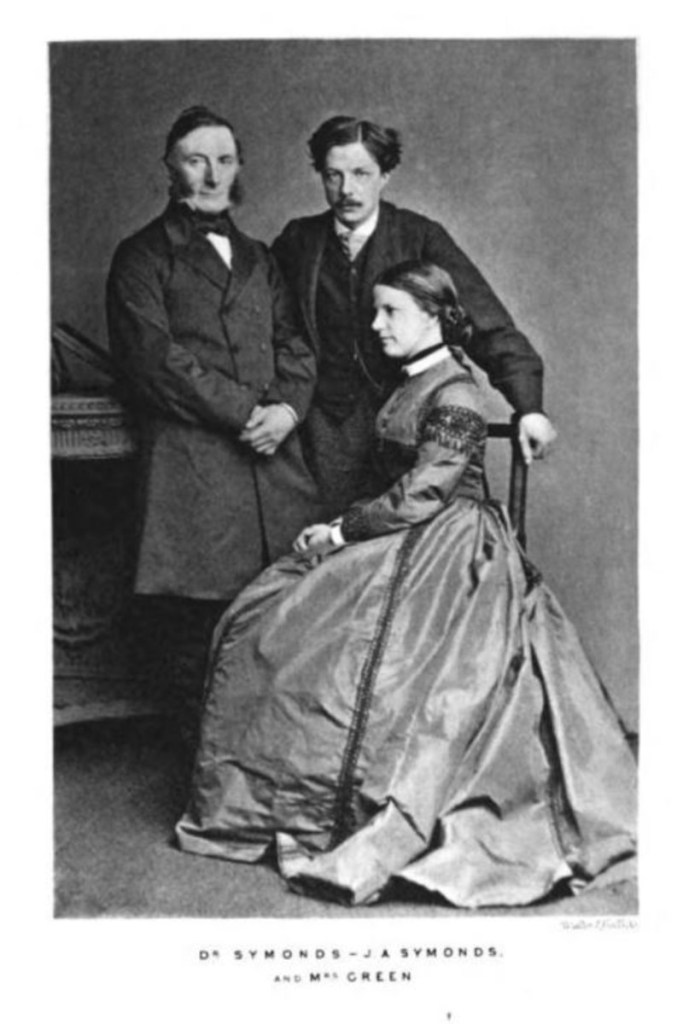

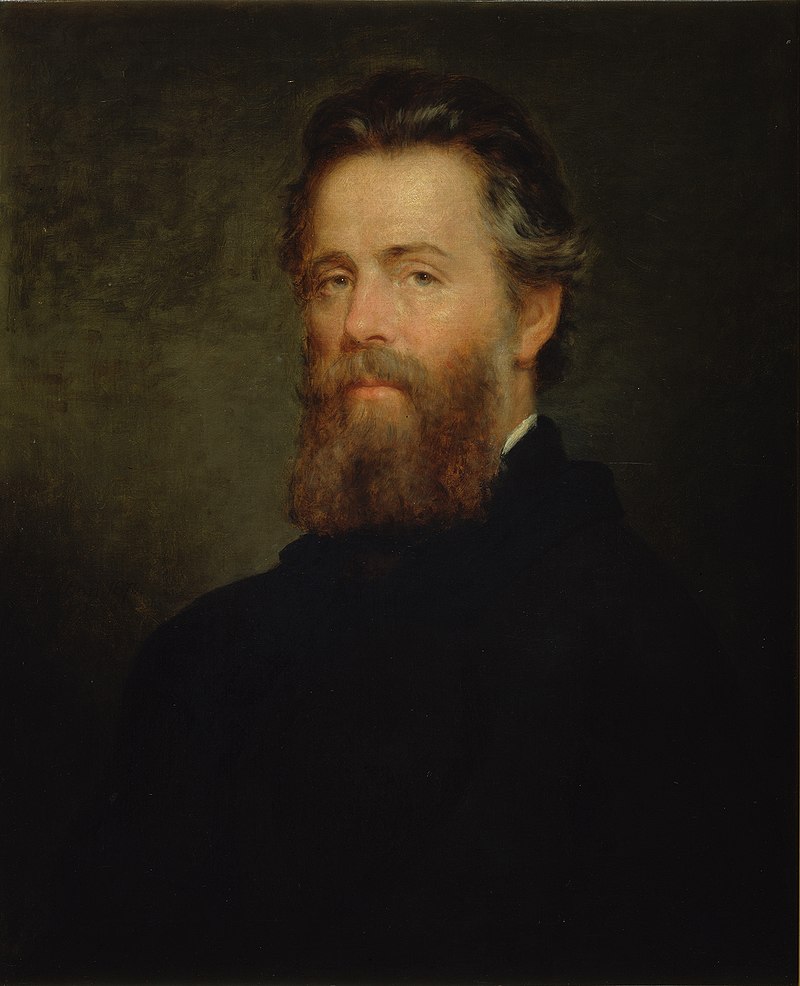

We can be confident that “L’Amour de L’Impossible” held great personal meaning to Symonds. After all, as Butler points out, “Symonds in his Memoirs reveals that its first six sonnets were written “about” his lover (and gondolier) Angelo Fusato” (Butler 177). While the ending of “L’Amour de L’Impossible” is certainly grim, I think it also betrays a strong resilience in the speaker, who forges ahead even though he knows he will find no rest in life or death. Symonds called his sexuality the “poison of his life,” but I think “L’Amour de L’Impossible” suggests that he never gave up on love, despite all the hardship he endured. Ultimately, the poem calls to mind the intense, life-long enterprise that Symonds endeavored in order to find a place for the love of the impossible in the world in which he lived.

Works Cited

Butler, Shane. The Passions of John Addington Symonds. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

“Chimera.” Apulian red-figure dish, ca. 350-340 BCE, Louvre, Paris. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chimera_Apulia_Louvre_K362.jpg

“Chimera | Chimaera, N.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, December 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1187663075.

Symonds, John Addington. “L’Amour de L’Impossible.” Animi Figura, Smith, Elder & Co., 1882. Retrieved from HathiTrust, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001020153.

Symonds, John Addington. The Memoirs of John Addington Symonds: A Critical Edition, edited by Amber K. Regis. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.